Mexico

-

Main languages: Spanish (official), numerous indigenous languages

Main religions: Roman Catholicism, indigenous religions

The overwhelming majority of the Mexican population is of mixed ancestry, with most people identifying as mestizo (mixed indigenous and Spanish ancestry). Official statistics had traditionally defined the indigenous population using criteria based on language, which many have argued greatly underestimates the increasingly urban population. However, indigenous peoples’ organizations were successful in pressuring the Mexican Statistics Bureau to include a broader set of criteria in the 2000 Census, including a question based on self-identification.

CONADI, the National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples, estimated that Mexico currently has 68 indigenous communities. In July 2017 the Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas reported that – based on 2015 figures – there were 25.7 million Mexicans who self-identified as indigenous, equivalent to 21.5 per cent of the national population at the time, with another 1.6 per cent identifying as part-indigenous. Over 12 million of these (more than 10 per cent of the national population) lived in indigenous households and some 7.4 million spoke indigenous languages. The most common indigenous language was Najuatl (23.4 per cent of indigenous language speakers), followed by Maya 11.7 per cent), Tzeltal (7.5 per cent), Mixteco (6.9 per cent), Tzotzil (6.6 per cent), Zapoteco (6.3 per cent), Otomi (4.2 per cent), Totonaca (3.6 per cent), Chol (3.4 per cent) and Mazateco (3.2 per cent).

The 2015 survey – a preliminary to a planned 2020 census – also revealed that 1.38 million Mexicans described themselves as being of African descent. The majority of Afro-Mexicans live in the state of Veracruz or along the Pacific coastal region of the southern states of Oaxaca and Guerrero, otherwise known as the Costa Chica.

-

Soaring violence in Mexico, with almost 16,000 homicides in the first half of 2018 – the highest levels in two decades – has left the country struggling to maintain the rule of law in the face of corruption, trafficking and powerful criminal cartels. The situation has been exacerbated by an increasingly militarized approach by authorities, with security forces themselves implicated in a range of human rights abuses. The deteriorating situation, while affecting all civilians, has impacted profoundly on journalists, lawyers and activists, particularly those championing minority and indigenous peoples’ rights.

The long roll call of civilians caught in the crossfire between armed groups or kidnapped, executed and forcibly disappeared includes numerous indigenous rights activists such as Isidro Baldenegro López and Juan Ontiveros Ramos, environmentalists and leaders from Chihuahua state’s Rarámuri (Tarahumara) indigenous people, killed in separate incidents in Guadalupe y Calvo municipality in early 2017. In May 2017, indigenous Tzotzil leader Guadalupe Huet Gómez was murdered in Chiapas state, just a few days after indigenous Huichol (Wixárika) land rights activists Miguel and Agostín Vázquez Torres – who had been fighting encroachment on their community’s lands by cattle ranchers – were killed in Jalisco state. The next day, at least 80 indigenous day workers at a ranch in Chihuahua also ‘disappeared’ after protesting labour exploitation by their employer. In another incident in February 2018, three activists of indigenous rights group CODEDI (Comité por la Defensa de los Derechos Indígenas) were killed in an ambush after a meeting with government officials in Oaxaca.

In addition, whole communities have been forcibly displaced by armed groups, political violence, land conflict and mining projects. In May 2018, the Mexican Commission on Defence and Promotion of Human Rights reported 25 such incidents in 2017, reportedly affecting over 20,000 people. Sixty per cent of the displaced were from indigenous communities: in some cases – such as that of the Mixe community of San Juan Juquila Mixes, Oaxaca state and the Tzotzil communities of Chalchihuitán and Chenalhó, Chiapas state – they were forced from their homes in the context of unresolved territorial or political disputes aggravated by the presence of armed groups. In all, members of at least six indigenous groups – Nahua, Tzotzil, Mixe, Rarámuris (Tarahumaras), Purépechas and Tepehuanes (Ódami) – were forcibly displaced in 2017.

In a broader context of impunity, weak governance and discrimination, those responsible for human rights violations and abuses – particularly against indigenous people – are rarely held to account. One exception was the conviction in June 2018 of two soldiers for the rape and torture of an indigenous woman, Valentina Rosendo Cantú, in 2002. The Inter–American Court of Human Rights found against the Mexican government in the case in 2010. The two soldiers were sentenced to 19 years in prison.

Hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans, Hondurans (including Afro-Hondurans) and Guatemalans (some of the latter indigenous) have fled north into Mexico in recent years, despite concerted efforts by Mexico to tighten control of its southern border and the corridors north. They enter Mexico in the knowledge that the path ahead is largely controlled by criminal networks in place to extort, exploit, terrorize, traffic or kidnap them for ransom. Mexico’s National Human Rights Commission estimated that in 2013 alone, 11,000 migrants were kidnapped: criminal investigations were opened in only a few dozen cases. Others were detained and returned by immigration officials, at times without due access to asylum procedures.

Many of those fleeing are children and youth seeking to escape persecution by the gangs that control the areas where they live. Given the increasingly hostile and restrictive US policy towards refugees, which has grown out of the Trump administration’s isolationism and rejection of international law, a small but growing proportion are seeking asylum in Mexico, with around 60 per cent of Central American applicants being granted refugee status or complementary protection. One key issue though is that the asylum procedure is characterised by long delays, leading to significant numbers – over 16 per cent in 2017 – abandoning or withdrawing their claims.

In response to pressure from families whose loved ones have gone missing while migrating through Mexico, new cross-border mechanisms for reporting and investigating enforced disappearance and other crimes against migrants have been set up. However, particularly in southern Mexico, they are being met by increasing anti-migrant prejudice in communities ill-equipped to cope with the number of new arrivals and influenced by some media and local officials’ negative portrayals of migrants.

-

Environment

Mexico is bordered by the United States to the north and Guatemala and Belize to the south. Although it is the largest and northernmost country of the Central American isthmus, it is today widely considered part of North America. The geography of Mexico is diverse, with a tropical southern region and coastal lowlands, more temperate central highlands, and an arid desert of the north and west. Mexico City is the largest metropolitan area in the world and has increasingly been the site of migration for many indigenous and rural workers in search of better opportunities.

History

Mexico has been inhabited for at least 11,000 years. Beginning centuries before the European conquest, a sequence of major indigenous civilizations flourished in the region, culminating with the militarily powerful Aztec empire, which arose in the early fifteenth century. Spanish colonization began in 1519 with the explorations and campaigns of Hernán Cortés. The Spanish conquerors quickly ascertained that the Aztec empire was not a monolithic entity and that some subjugated nations could be turned to the Spanish side. Large numbers of indigenous troops supported his decisive attack on the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. Cortés brought a number of enslaved Africans among his servants and military. They became the first of approximately 200,000 slaves from Africa to arrive in Mexico during the colonial period. Veracruz was arguably the most important slave port in the Americas throughout sixteenth century.

Spanish colonialism had many different impacts on the pre-existing societies after the conquest. Forcible conversion to Christianity was the rule. Diseases previously unknown in the Americas, against which the indigenous population had no immunity, resulted in millions of deaths. The Spanish colonial authorities relocated indigenous communities into fewer, larger towns where they could be more effectively controlled, and on to the least fertile lands. The Europeans themselves took possession of the rich soils that had provided bountiful and reliable harvests of maize, beans and squash for the indigenous communities.

With the participation of creolized Africans and indigenous people, Mexico achieved independence from Spain in 1821. The establishment of a republic in 1824 was followed by a period of political instability, and war with Britain, France and the US. Mexico ceded much of its territory to the US after the war of 1846. Stability was regained in 1876 under the dictator Porfirio Díaz. The following decades witnessed significant growth in Mexico’s economy and the consolidation of landownership in the form of huge haciendas (estates) in the hands of a small and wealthy Spanish-descended elite. Tricked into debt-bondage, large numbers of indigenous Mexicans worked on the haciendas as virtual slaves. Severe poverty was rampant among the indigenous peoples, African descendants and the majority of the mestizo population.

The exploitation and impoverishment of the rural and urban masses, combined with a lack of democracy, led to the revolution of 1910–20. Among other reforms, the subsequent constitution of 1917 revised landownership and drafted a labour code. Indigenous peoples’ rights were ignored. Established in the wake of these events, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) maintained until very recently a monopoly on political power, despite accusations of electoral irregularities.

A concerted effort to industrialize and modernize Mexico’s infrastructure took place from the later 1940s onwards. The establishment of ejidos – communal peasant farms on state-owned land – through the expropriation of large capitalist farms was a central project of the government of President Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–40). However, subsequent administrations favoured capital-intensive export agriculture and neglected the ejido sector, where most of the country’s corn producers, including the majority of indigenous farmers, were concentrated. This led to a loss of self-sufficiency in basic grains and greater reliance on imports in the 1970s.

Economic crisis was temporarily overcome in the second half of the 1970s, when large oilfields were discovered and high world prices for oil allowed the government to increase revenue and attract massive foreign loans. The oil-debt boom came to an abrupt end in 1982 as a result of the simultaneous fall in oil prices and rising interest rates of international creditor banks. A period of austerity and economic restructuring followed, culminating in 1994 with Mexico’s decision to approve the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In direct opposition to this agreement, in January 1994, the National Zapatista Liberation Army (EZLN or Zapatistas) staged an armed rebellion. This pan-indigenous and rural peoples’ movement, which gained international attention and support, demanded land reform, autonomy and collective rights for indigenous peoples. Since then, the EZLN have refrained from further military action, but it remains a strong presence in a large part of Chiapas province. The legacy of the conflict also persists in the continued uprooting of many civilians by the violence: according to a 2015 report by the International Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), some 25,000 people remained displaced in Chiapas as a result of the 1994-95 Zapatista conflict.

In more recent years, Mexico has continued to be plagued by corruption, political violence and the increasing entrenchment of a brutal network of criminal cartels sustained by drugs, arms and human trafficking. The steady rise in homicide levels, reaching a two-decade peak in 2018, has particularly affected many indigenous and minority communities targeted by armed groups.

Governance

Democracy and the rule of law in Mexico have been increasingly undermined by chronic levels of political violence, reflected in the most recent 2018 elections. Between the beginning of campaigning for local, regional and national elections in September 2017 and the end of polling day in July 2018, 48 candidates had reportedly been killed. Andrés Manuel López Obrador of the Juntos Haremos Historia (Together We’ll Make History) coalition was elected President with 53 per cent of the vote. Running on an anti-corruption platform and promising to replace the militarised approach of previous governments to public security with alternative peace-building measures, he won in all but one state. The historically dominant Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) of incumbent president Peña Nieto won just 16.4 per cent of the vote, its worst result in decades. Obrador’s election was seen as potentially positive for indigenous peoples’ rights in Mexico: his campaign pledges had included, for instance, establishing bilingual schools in areas with a majority indigenous population.

Mexico’s justice system continues to be defined by widespread impunity for military forces and inadequate protection for victims of abuses from state and non-state actors, including human rights activists. Judicial reforms dating back to 2008 have still only been implemented in a fraction of the country’s 32 states, with many pieces of recent human rights legislation still largely unimplemented due to a lack of political will or resources.

In an effort to protect citizens against human rights abuses, in 1990 the Mexican government established the National Commission of Human Rights, which receives complaints of abuses at the federal and state levels. However, since then this agency has been criticized for failing to take on cases of grievous rights violations, leading many indigenous leaders and rights activists to question its credibility. Nevertheless, the Commission produces reports and publications drawing attention to Mexico’s human rights record. The government also ratified International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 169 of 1989 on the rights of indigenous and tribal peoples, although it is argued that constitutional reforms have undermined land rights guaranteed under the Convention.

The Law for the Prevention and Elimination of Discrimination was enacted in 2003. It prohibited racially offensive messages and images in mass media, and discriminatory practices in general. It also mandated the creation of the National Council for the Prevention of Discrimination as a federal agency in charge of preventing and eliminating discrimination, as well as formulating and promoting public policies for equal access to opportunities for all. At the local level, the majority of provinces in Mexico now have specific laws and institutions to address discrimination. These played a major role in combating discrimination and placing the issue on the public agenda. Mexico adopted the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007.

Officially, Mexico’s indigenous communities are protected by human rights legislation. The government’s National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CONADI) – replacing the National Indigenous Institute in 2003 – has offices throughout the country to facilitate consultation with indigenous communities, and government statements are careful to recognize the principle of cultural diversity.

-

Amnesty International

Website: www.amnistia.org.mxAsociación México Negro

Website: https://es-la.facebook.com/MexicoNegroAcCentro de Derechos Humanos ‘Fray Francisco de Vitoria OP’

Website: http://derechoshumanos.org.mxComisión Mexicana de Defensa y Promoción de los Derechos Humanos

Website: http://cmdpdh.orgComisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (CNDH)

Website: http://www.cndh.org.mxComisión Nacional Para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas

Website: https://www.gob.mx/cdi

Updated May 2020

Related content

Minority stories

-

25 February 2016

Life at the Margins: The Challenges of Multiple Discrimination

Minorities and indigenous peoples, already marginalised, face further challenges on account of other aspects of their identity – their age, gender, livelihood, disabilities, sexuality or gender identity.

- East Africa

- Discrimination

- Minority stories

Reports and briefings

View all-

1 June 1995

No Longer Invisible: Afro-Latin Americans Today

The distinct but extraordinarily diverse ethnic and cultural identities of Afro-Latin Americans have received little official recognition….

-

1 July 1987

The Amerindians of South America

For over 20,000 years a wealth of many cultures flourished in South America, both in the high Andean mountains and the lowland jungles and…

-

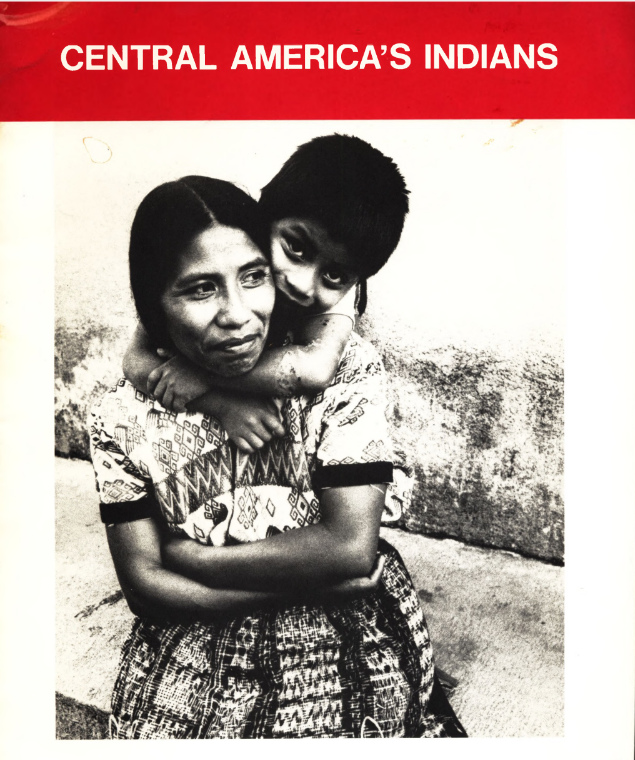

1 April 1984

Central America’s Indians

In Latin America today we find one of the largest remnants of colonialism in the world. The concept “Indian” itself is, of course, a…

Programmes

Events

-

Video on demand

Video on demand 21 July 2023 • 5:00 – 7:00 pm BST

Water Justice in the Americas Symposium

Organized by The Splash Project with Minority Rights Group International (MRG), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Mérida and…

Don’t miss out

- Updates to this country profile

- New publications and resources

Receive updates about this country or territory

-

Our strategy

We work with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples to secure their rights and promote understanding between communities.

-

-