Haiti

-

Main languages: Creole, French

Main religions: Christianity (Roman Catholic), syncretic African religions (voodoo)

The overwhelming majority of the population (around 95 per cent) of Haiti is predominantly of African descent.

The rest of the population is mostly of mixed European-African ancestry (mulatto). There are a few people of Syrian and Lebanese origin. There is also a community of Europeans of Polish origin and a small minority of people from the Dominican Republic. Most of the country’s population is concentrated in the rural coastal plains, and valleys and in the urban areas.

Haiti’s official languages are French and Kreyòl Ayisyen (Haitian Creole). Nearly all Haitians speak Kreyòl Ayisyen, with French being spoken by the small group of educated people. Many Haitians also speak English and Spanish, particularly due to the proximity of the Dominican Republic and Cuba and the extent of travel and trade between the nations.

Catholicism is the formal state religion and there is a considerable Protestant minority. The largely African-based religious system known as Voudon is recognized as an official religion and is practised by a majority of the population. Voudon incorporates African, Taíno-Arawak ancestors and those of the Catholic saints in a syncretistic spiritual structure. Due to centuries of demonization by formal churches and stereotyping and ridicule by the secular world, most of the population prefers to conceal their simultaneous adherence to this faith.

An important demographic dimension in Haiti is the continued pull of emigration, with hundreds of thousands of Haitians abroad, with communities not only across the Caribbean, primarily in the Dominican Republic but also in the Bahamas, the Turks and Caicos Islands (TCI) and the French overseas departments, départements d’outre-mer (DOMs), of French Guiana (Guyane), Guadeloupe and Martinique. The United States is also a significant destination, with a large population of some 700,00 Haitian immigrants in the country, while other destinations have also become increasingly popular amidst the increasingly hostile environment promoted by US President Donald Trump and his administration. In 2017, for instance, more than 100,000 Haitians – around 1 per cent of the Haitian population – entered Chile, though Chilean authorities have increased entry restrictions for Haitians in response.

-

One of the poorest countries in the world, Haiti has long struggled with the legacy of colonialism, slavery and chronic poverty. Despite gaining independence more than two centuries ago from France after a successful uprising by the enslaved population, leading to the creation of a ‘Black Republic’, much of the repressive infrastructure of the former colony remained in place. Long marginalized by other countries in the region, Haiti has more recently achieved greater recognition of its vibrant cultural heritage: nevertheless, its history of authoritarianism, military occupation and brutal repression continue to be felt, with many of the population still struggling against a backdrop of political instability, violence and lack of access to basic services such as education.

Haiti is one of the most exposed countries to natural disasters, including earthquakes, hurricanes and floods. While the destruction and death toll of the 2010 earthquake was unprecedented, Haiti has regularly been subjected to catastrophic events, including the Category 4 Hurricane Matthew that struck Haiti in October 2016, leaving the south and west of the island particularly devastated, with the most impoverished worst affected. The reconstruction of the country, despite billions of dollars in international funding, has been slow and millions remain in need of humanitarian assistance.

Displacement and homelessness remain a crucial issue. In 2018, nearly 38,000 people remained in the displaced camps established after the 2010 earthquake. The camps are inadequate for the population they serve: 17 of the 26 camps have insufficient sanitary facilities. The vast majority of camp residents – an estimated 70 per cent – are women and children. And 140,000 households are still in need of proper shelter after having been affected by Hurricane Matthew.

While the country has seen some improvements in poverty reduction, it remains the most unequal country in Latin America and the Caribbean, and continues to struggle with a range of social problems including sexual violence, child trafficking and gang violence. For decades, limited opportunities, poor governance and more recently the devastation of the 2010 earthquake that left more than 220,000 dead and flattened much of the capital, Port au Prince have driven a wave of emigration from Haiti. This has created a large diaspora of Haitians, numbering well over a million, concentrated particularly in the United States, Dominican Republic, Canada and Bahamas, with a sizeable population also resident in France. Haitian minorities in these countries typically experience high levels of discrimination and exclusion, with their vulnerability as migrants further heightened by racism.

The largest Haitian community resides in the neighbouring Dominican Republic, where Haitians as well as Dominico-Haitians (those born in the Dominican Republic with claims to Dominican citizenship) form a large minority in the Dominican Republic. For decades they have been crossing the border, either by invitation or illegally, to work on sugar plantations or in other agricultural or manual employment, doing the work that Dominicans have traditionally refused to do. But today, as the Dominican government is attempting to abandon its age-old dependence on sugar, and develop manufacturing, tourism and other sectors, Haitian labour is again filling the gaps left by Dominican workers.

Haitians are both needed and widely disparaged as a migrant minority. For Dominican employers they offer a reservoir of cheap labour, which is non-unionized and easy to exploit. Meanwhile, Dominican politicians and the media often depict them as a problem, as a drain on a poor country’s limited resources. Racist attitudes also condemn Haitians and their children as blacker than Dominicans, ‘uncivilized’ and ‘inferior’.

Their situation has been exacerbated by official discrimination, particularly since September 2013 when the Dominican Republic’s Constitutional Court issued judgment TC/0168/13, stripping hundreds of thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent of their Dominican nationality. This included all Dominicans whose parents were not born in the country and was retroactive for anyone born in 1929 or later. This judgment has paved the way for the mass deportation of many Dominicans of Haitian descent and Haitian immigrants to Haiti, as well as exacerbating the already entrenched discrimination experienced by these individuals.

Although the Dominican government implemented a temporary 18-month suspension of mass deportation in December 2013 in order to allow undocumented foreigners to regularize their status, these deportations resumed in June 2015. Since then, thousands have been deported from the country, including many with valid claims to Dominican citizenship, and the situation for those who remain in the country has deteriorated dramatically. This official crackdown has been accompanied by widespread popular xenophobia and outbreaks of anti-Haitian violence by vigilantes that have forced many to leave the Dominican Republic.

Their marginalization is replicated elsewhere, including in the United States, where around one in five of the approximately 700,000 Haitian immigrants in the country live in poverty, significantly higher than the average for US-born Americans. Haitian immigrants have faced an increasing crackdown under the Trump administration, with the announcement in 2017 that an estimated 60,000 Haitians with around 30,000 US-born children who were granted legal residency after the 2010 earthquake would have their Temporary Protection Status revoked, forcing them to return to Haiti by July 2019. Meanwhile, other countries have seen a rapid increase in Haitian immigration, including Chile, where in 2017 more than 100,000 Haitians immigrants – around 1 per cent of Haiti’s population – moved to the country.

-

Environment

The Republic of Haiti occupies the western third of the island of Hispaniola, which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Haiti is bounded on the north by the Atlantic Ocean, on the south by the Caribbean Sea, and on the west by the Windward Passage. On the east a 360 km border separates it from the Dominican Republic. Haiti also possesses a number of smaller islands including La Gonâve, La Tortue (Tortuga), Les Cayemites, Île de Anacaona and La Grande Caye. The total area of the country is 27,750 sq km.

History

Pre-Columbian period

The original inhabitants of the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti/Dominican Republic) were the indigenous Taíno, an Arawak-speaking people who began arriving from the Yucatan peninsula as early as 4000 BCE.

Joined later by successive additional waves of people from the Orinoco/Amazon region of South America (present-day Venezuela) the Taíno settled all across the Caribbean and became known as the Island Arawaks.

The name Haiti is derived from the indigenous Taíno-Arawak name for the entire island of Hispaniola, which they called Ay-ti ‘land of mountains’.

It was Christopher Columbus who renamed it La Isla Española (‘The Spanish Island’) when he arrived in 1492. This later evolved into the name Hispaniola.

Spanish colonial settlement

The Spanish were slow to settle the island. The Taíno-Arawak destroyed the first Spanish settlement and Spanish attempts to obtain gold using Taíno labour after 1502 proved unprofitable. There was continued indigenous resistance and Taíno-Arawak who were not killed disappeared into the remote mountains.

Spanish establishment of sugar plantations did not meet with long-term success. The Spanish introduced sugar cane from the Canary Islands after 1516 and the need for forced labour on the plantations led to a sharp increase in the importation of West Africans. It also led to the first major slave revolt in the Americas in 1522.

Enslaved West Africans (Wolof Muslims) led an uprising on the sugar plantation owned by Diego Colón, the son of Christopher Columbus. Many of the insurgents escaped to the mountains and formed the first independent African Maroon community in the New World. Thereafter, increasing numbers of imported Africans kept escaping into the island’s interior and linked up with residual pockets of indigenous Taíno-Arawaks, creating expanding communities of African Maroons (literally, ‘escaped slaves’). By the 1530s, Maroon resistance bands had become so dangerously pervasive that large armed groups were required for travel outside the fledgling Spanish plantations.

This led to a severe restriction on Spanish movement, which allowed British and French buccaneers and their indigenous guides to begin using the nearby island of La Tortue (Tortuga) and the western portion of the island for hunting wild pigs and other animals to produce bucan (dried meat) for sale to passing ships.

France established direct control over Tortuga in the early 1600s and from there expanded to the north coast of Hispaniola.

French colonial settlement

French settlement on Hispaniola began in 1625. In 1664 France formally claimed the western portion of the island, which they called Saint-Domingue. The French established large sugar and coffee plantations and over the years brought in millions of enslaved Africans to provide forced labour. These highly profitable operations soon made it the richest colony in the Western hemisphere.

Notoriously brutal plantation conditions ensured a short life-span for slaves, which resulted in regular replacement with fresh African captives and constant maroonage.

Thousands of Africans escaped into the remote mountain areas, established free Maroon settlements and interacted with communities of indigenous Taíno-Arawaks that existed well beyond French or Spanish control.

By 1790 (a year before the revolution) the colony’s population totaled more than 500,000 enslaved African workers; 28,000 free ‘gens de couleur‘ (mostly Euro/African mixture) functioning as an intermediate class and about 30,000 Europeans (French), who held all political and economic control.

Haitian revolution

In August 1791, enslaved Africans in the north rose in rebellion. The revolution spread quickly, eventually coming under the leadership of locally born Toussaint L’Ouverture who soon formed alliances with the free gens de couleur and the African Maroons.

By 1794 forces under Toussaint L’Ouverture had succeeded in overcoming the French colonial army, resisting invasions by British and Spanish forces, and had liberated the entire colony from French control. As a result of these unprecedented upheavals, Napoleon Bonaparte sent a contingent of French troops in 1801 to subdue the colony and reinforce slavery.

Toussaint L’Ouverture was captured and taken to France where he died in prison the next year. This caused the other revolutionary leaders Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Alexandre Sabès Pétion and Henri Christophe, to resume the liberation war. The French forces were decimated, and on 1 January 1804 the new nation declared independence. It became the second independent republic in the New World after the United States and was called Haiti in recognition of the old Taíno-Arawak name.

In 1806 Dessalines was assassinated and, for the next decade, the northern part of Haiti was ruled by Christophe while the southern part was under the control of Pétion.

Seeking to make Haiti an internationally respected black nation, Christophe revived sugar production using an unrelenting military system. This brought production back to up to two-thirds of pre-revolutionary levels, however it alienated his officers who mutinied causing Christophe to take his own life rather than face the rebellious generals.

Following Christophe’s death in 1820 the northern and southern regions were reunited as the Republic of Haiti under Jean-Pierre Boyer. When the Spanish-controlled western portion of the island sought to gain its own independence in 1821, Haitian forces invaded that colony and united the entire island of Hispaniola for the next 22 years (see Dominican Republic)

Superpower sanctions

The Haitian Revolution was a stunning development in the world of the nineteenth century, representing an inspiration for some and causing great trepidation in others. In an era convinced of black inferiority and highly dependent on slave labour, the success of the revolution was seen by some as an unforgivable affront to European pre-eminence and prompted widespread calls for punitive measures.

Besides helping to inspire numerous slave revolts in the Caribbean and United States, the new republic was instrumental in hastening the eventual abolition of slavery. It widely supported the regional abolitionist cause. Among other actions, Haiti provided sanctuary and financing for Simón Bolívar and the ultimately successful Latin American revolution, on condition that he put an end to slavery in that region (see Venezuela).

Prompted by fears of the rapid spread of slave rebellions to other territories, all the slaveholding superpowers imposed a total blockade on Haiti, effectively isolating the new nation from participation in the international world.

France refused to recognize Haiti’s independence for three decades, until it agreed to pay 150 million francs compensation for the French plantation owners’ losses. The Vatican withdrew its priests and did not return them until 1860, when Santo Domingo relinquished its own independence to Spain (see Dominican Republic).

The reparations to France in 1833 plunged the government of Haiti deeply into debt and permanently crippled the country’s economy. In 1844 the eastern two-thirds of the island became emboldened enough to declare its independence, becoming the Republic of Santo Domingo (today, the Dominican Republic).

Throughout the nineteenth century, Haiti was ruled by a series of short duration presidents reflecting an ongoing struggle for political pre-eminence between the mixed–race mulatto urban minority and the large black rural majority with whom they did not identify. Moreover, under the ever-present burden of debt, the country’s economy gradually came to be dominated by foreigners, particularly from Germany.

US involvement

During the First World War (1915) the United States – then already in control of the Dominican Republic – invaded and occupied Haiti over concerns about the extent of German influence in the region. This initiated an era of direct US involvement in Haiti’s affairs.

Under US occupation, infrastructure was built up, administrative systems introduced and government and industry centralized. However, this power shift from the provinces to the capital helped to usher in the destruction of the traditional African-based self-reliant socio-economic fabric of the country. Moreover, it prompted an exodus from the countryside.

A war of resistance against these reforms initiated by Nationalist rebels (Cacos) in 1920 prompted the US-controlled government to create a National Guard that later became the infamous Armée d’Haiti (Haitian Army).

The US ended its occupation in 1934 leaving the country under the control of the mixed–race minority centred in the capital, Port au Prince, with the US trained and equipped Armée d’Haiti ready to serve and protect their interests. It also left a space open for greater involvement in Haitian affairs of the Dominican Republic sugar industry.

Beginning in the late 1920s the first Haitian braceros or cane-cutters were taken across the border to work in the US-controlled Dominican sugar industry. By 1935 the census recorded a cross-border Haitian population of 50,000.

With the depression of the 1930s and a precipitous drop in sugar prices, a crisis developed. In response the Dominican dictator, General Rafael Trujillo, ordered the massacre of Haitian migrants by the armed forces of that country, leading to the deaths of between 20,000 and 25,000 Haitians.

Despite the massacre, subsequent Haitian governments signed contracts with the Dominican authorities, notably the State Sugar Council (CEA), allowing the recruitment of Haitian braceros in return for a per capita fee.

Militarization

In 1946 following the military ousting of Elie Lescot, who had ruled since 1939, Dumarsais Estate succeeded in becoming the country’s first black president since the American occupation. However, his efforts at reform sparked a Dominican Republic-sponsored crisis which led to his eventual resignation in 1950.

The Military Council of Government assumed control while steps were taken to prepare the country for universal suffrage and, in 1957, Dr François Duvalier (‘Papa Doc’) was elected by popular vote.

Duvalier’s regime first attracted international criticism in the 1960s for its human rights violations. This included the harsh treatment of potential political adversaries by the Volunteers for National Security, the secret police organization, also known as the Tonton Macoutes.

Some anti-Duvalier elements chose to go into exile in the neighbouring Dominican Republic and already strained relations between the two countries deteriorated in 1963 when an anti-Duvalier military plot was exposed and crushed. Haitian police invaded the Dominican embassy to seize asylum seeking anti-government plotters, which led to a build-up of Dominican government troops on the Haitian border.

However, none of this stopped the continued recruitment of Haitian braceros to work in the Dominican sugar industry or the per capita fees that were paid in return.

Death of Papa Doc and the exodus of Haitian migrants

Upon his death in 1971, Duvalier was succeeded by his 19-year-old son Jean-Claude Duvalier (nicknamed ‘Baby Doc’), who was backed by a shadow cabinet. He was subsequently deposed in 1986 and allowed to go into exile.

For centuries the effects of the virtual quarantine imposed on Haiti after the 1791 Revolution had been mainly confined to the impoverished and marginalized Haitian majority. Their existence continued to be of little concern to the international community as long as they stayed in territorial isolation. However, the situation began to change drastically following the death of ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier.

The political oppression and deepening poverty into which the country slipped during the late 1970s and early 1980s stimulated an unprecedented exodus of Haitian refugees to the Bahamas and the US. It especially drew increased international attention to the country’s internal situation.

Aristide’s arrival

A popular movement supported by local churches helped hasten the disintegration of the Jean-Claude Duvalier regime. In a strongly religious country, it was also partially inspired by the 1983 visit of Pope Jean Paul II, during which he forcefully advocated the need for change.

In December 1990, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, a former Roman Catholic priest, became the first democratically elected president in the history of Haiti. He was swept to power largely with the aid of a network of faith-based popular grassroots organizations. He earned two-thirds of the vote, defeating the internationally favoured rival Marc Bazin, a former World Bank official.

Aristide attempted progressive reforms, reduced corruption and trimmed state bureaucracy. The migrant labour agreement with the Dominican State Sugar Council (CEA) was also ended. The exodus of refugees virtually stopped and human rights violations were reduced to below previous levels.

However, Aristide’s actions and populist stance seriously alarmed the elite, and he was deposed by a violent military coup just seven months after taking office.

Aristide’s departure

This ushered in three years of harsh military rule, including reprisals against grassroots political activists. The flow of refugees once again rose significantly. Many poured across the border into the Dominican Republic. Others risked their lives in unsafe, overcrowded boats and rough seas, heading directly or indirectly to the United States, Canada and other Caribbean territories.

In a move reminiscent of the nineteenth century, the US administration introduced a containing blockade against Haiti. The US Coast Guard intercepted many refugee boats while others were lost at sea. Of the thousands attempting to flee, more than half were sent back to Haiti.

With the crisis worsening, the United Nations also imposed broad sanctions to get the military to step down. However, this additional economic embargo, which included petroleum products, only increased the level of hardship for the Haitian majority. The number of Haitians fleeing the country in search of political asylum greatly increased, with some 20,000 attempting to reach US shores during 1994.

Aristide’s return

The political deadlock in Haiti ended in 1994 with an invasion of US Marines aimed at supporting Aristide’s return to power. The Haitian Army generals went into exile as well as the Chief of Police who crossed into the Dominican Republic.

Aristide’s return raised hopes for peace but not necessarily for economic improvement. The majority of the Haitian population continued to see their best hopes and prospects in continued economic emigration.

Much of Haiti’s already limited infrastructure – including bridges, roads and port facilities – had deteriorated during the military regime. Moreover, the international embargo had crippled an already weak economy, driving it close to collapse.

The Armée d’Haiti was disbanded and elections held in 1995, in which René Préval, a former prime minister, was elected. However, social and political tensions remained and the previously imposed blockades continued in other ways.

The United States, which was Haiti’s largest funder, froze economic aid, citing delays by Aristide’s government in implementing economic reforms. These reforms involved the privatization of key state-owned companies such as banks, the electricity and telephone utilities, and the country’s main port.

In 2001, despite weakened civil society aspirations, Aristide managed to be popularly re-elected and to hang on to office in the face of intense external pressure for reform.

Citing undemocratic behaviour, in 2003 the US government vetoed the delivery of US$500 million in approved Inter-American Development Bank aid loans to Haiti. These social sector funds were earmarked specifically for improving education, health and clean water supply, all of which were aimed at the poor and marginalized Haitian majority.

Aristide’s exit

In February 2004, the Aristide government was once again impatiently ousted by rebels. Having already disbanded the army, the coup was undertaken by well-equipped urban gangs and demobilized soldiers of the former Armée d’Haiti, who began their invasion from a staging area very close to the Dominican border.

In the ensuing turmoil, Aristide was forced into exile under US escort. In the b

-

Institute for Justice & Democracy in Haiti (IJDH)

Website: http://www.ijdh.org/Plateforme des Organisations Haïtiennes des Droits de l’Homme (Institut Culturel Karl Lévêque)

Website: http://www.ickl-haiti.org

Plateforme Haïtienne de Plaidoyer pour un Développement Alternatif

Website: http://www.papda.orgRéseau National de Défense des Droits Humains

Website: http://www.rnddh.org

Updated May 2020

Related content

Latest

-

30 November 2018

MRG Statement at the 11th Session of the Forum on Minority Issues

The following statement was delivered at the 11th Session of the Forum on Minority Issues in Geneva on 30 November 2018 by Shikha Dilawri,…

Reports and briefings

View all-

1 July 2003

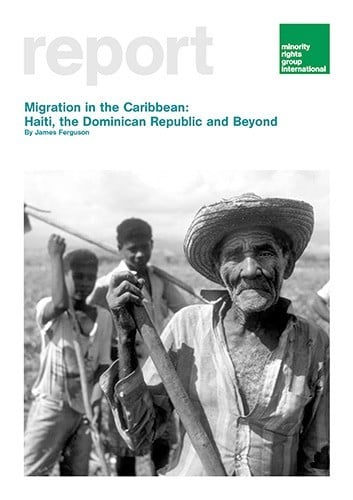

Migration in the Caribbean: Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Beyond

This Report aims to cast light on the conditions experienced by often invisible minority migrant workers in the Caribbean, looking at…

-

1 July 1987

The Amerindians of South America

For over 20,000 years a wealth of many cultures flourished in South America, both in the high Andean mountains and the lowland jungles and…

-

1 April 1984

Central America’s Indians

In Latin America today we find one of the largest remnants of colonialism in the world. The concept “Indian” itself is, of course, a…

Don’t miss out

- Updates to this country profile

- New publications and resources

Receive updates about this country or territory

-

Our strategy

We work with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples to secure their rights and promote understanding between communities.

-

-