Palestine

-

Main languages: Arabic, Hebrew

Main religions: Islam, Judaism, Christianity

The overall Palestinian population in the West Bank and Gaza Strip is 4.8 million (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2017), including 2.9 million in the West Bank (including an estimated 27,000 Bedouin within Israeli-controlled Area C) and 1.9 million in the Gaza Strip. An estimated 435,000 Palestinians reside in East Jerusalem.

Close to 99 per cent of Palestinians are Muslims, with Christians making up less than 1 per cent of the population (PCBS, 2017) with small numbers of members of other communities including around 400 Samaritans resident in the West Bank. In addition, there are now more than 600,000 Israeli settlers in East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

Main languages: Arabic, although many also speak Hebrew, English and French.

The PCBS puts the total Palestinian population worldwide at 12.7 million, with over 1.5 million within Israel, 6 million in other Arab countries (primarily as refugees) and 700,000 in other countries (PCBS, 2017). As many as 5 million Palestinian refugees are eligible for UNRWA assistance, including 1.3 million in Gaza and around 800,000 in the West Bank. In addition there are around 335,000 Palestinians in Israel who, though they have Israeli citizenship, are unable to return to their homes. Over 2 million UNRWA-registered refugees reside in Jordan, 450,000 in Lebanon and 440,000 in Syria.

Most Palestinians are Sunni Muslims, but some are Christians of various denominations. A small community of Arab Samaritans, numbering around 400, live mostly near the West Bank town of Nablus, with similar numbers based in Israel, near Tel Aviv.

After 1967, Israeli settlers increasingly moved into the occupied territories. There are now more than 600,000 settlers in East Jerusalem and the West Bank. Settlers belong to two broad categories: those who have settled for ideological reasons, often in the least hospitable areas, and a larger number of those who have settled in the metropolitan commuter areas of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv because of the opportunity to inhabit good housing much more cheaply than inside Israel.

The presence of Israeli settlers violates the requirements of the Fourth Geneva Convention regarding protection of civilian populations under occupation. Settlers are subject to Israeli law, not to the laws applying to the occupied territories. Many settlers, especially those who are motivated by ideology, are armed and may shoot unarmed Palestinians when they believe the circumstances justify this. Settlers have used this authority to carry out attacks on Palestinians, and settlers are also targeted for violence by Palestinian militants. The international community has taken few effective steps to persuade Israel to terminate settler violations of the Geneva Convention.

-

For the marginalized and besieged communities of the State of Palestine, which for decades have faced evictions, security crackdowns and profound social exclusion, the prospects of a more inclusive and peaceful future remain bleak. Since the annexation of East Jerusalem and large areas of Egypt, Jordan and Syria in 1967 following the outbreak of conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbours, the continued illegal construction of settlements in the occupied Palestinian territory has been an ongoing source of friction that has served to further entrench the conflict. Israeli-only settlements in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) have continued to grow. For instance, in July 2016 the Israeli government approved US$13 million in financing construction inside Hebron as well as nearby Kiryat Arba. In December 2016, the Jerusalem municipal government announced it would move ahead with thousands of new homes in the east of the city. A ‘validation’ bill allowing for retroactive legalization of settlements built on expropriated private Palestinian lands in the West Bank passed its first votes in the Knesset in early December and became law in February 2017. The pace of construction has continued unabated, with the Israeli defence minister announcing in June 2017 that the number of settler homes constructed in the first months of 2017 were the highest since 1992: official statistics show that the number of homes commenced between April 2016 and March 2017 had risen by 70 per cent to construction starting on 2,758 new units. Further rounds of settlement expansion have continued since then. In September 2017, the Jerusalem municipal government announced that 176 housing units would be built in the Nof Zion settlement, nearly tripling it in size, in the Palestinian Jabel al-Mukaber neighbourhood of East Jerusalem. In May 2018, the government announced that 2,500 new homes had been approved and that a further 1,400 were in the pipeline. For the whole of 2018, the European Union (EU) recorded a total of more than 15,800 units that had been advanced during the year (9,400 homes in the West Bank and 6,400 in East Jerusalem) – enabling more than 60,000 Israeli settlers to move to the Occupied Palestinian Territory. An additional 4,461 homes for settlers were announced in February 2019 to be built in and around Jerusalem. Around 215,000 Israeli settlers already reside in East Jerusalem, leading at times to serious friction with the Palestinian population there. An estimated 630,000 settlers live in the Occupied Palestinian Territory. There are currently 143 settlements, 11 of which are in East Jerusalem, and 106 outposts. While illegal settlement growth has long persisted despite international condemnation, at the end of 2016 in an unprecedented step UN Security Council Resolution 2334 was passed after the United States for the first time ever abstained from voting rather than exercised its veto on a resolution condemning Israeli settlement building as a violation of international law and a major obstacle to the achievement of a two-state solution to the conflict. After the resolution, plans were postponed until US President Donald Trump took office in January 2017 for Israeli authorities to approve building permits for 566 homes for Jewish settlers in occupied East Jerusalem. A plan to build 2,500 new settlement homes in the West Bank was also announced, suggesting that contrary to previously declared support for a two-state solution, the right-wing Likud government intended to expand its territorial acquisition and undermine the creation of a contiguous Palestinian state. Since the beginning of the Trump administration, the long-established opposition of the US to settlements appears to have softened, with the US Ambassador to Israel stating that they were ‘part of Israel’. These comments reflect a broader shift in US policy, encompassing the rollback of humanitarian aid funding to Palestinian refugees and the recognition by Trump in December 2017 of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel – an unprecedented move that received widespread condemnation. These and other signals from Washington DC appear to have triggered much of the current wave of settlement expansion since then. Non-Jewish residents inside Palestine have faced unprecedented levels of home demolitions and displacement since records began in 2009. In 2016, this reached a peak with 274 homes and hundreds of other Palestinian-owned structures in the West Bank destroyed, while more than 1,134 people were displaced. While the frequency of these demolitions appears to have reduced since then, B’Tselem records 1,424 homes having been demolished and 6,269 people being left homeless in the period from 2009 through May 2019. The organization lists demolitions in East Jerusalem separately; there it has recorded 848 homes having been destroyed since 2004 leading to 2,960 people being rendered homeless. Palestinian residents have in numerous cases been forced to destroy their own homes in order to avoid paying costly demolition fees. As most live under the poverty line, they face barriers in applying for building permits including convoluted years-long processes and prohibitive costs reaching up to around 300,000 shekels (USD $80,000). Among those worst affected are the 27,000 Bedouin living in the Israeli-controlled Area C of the West Bank face constant threats of displacement. Unlike the Bedouin in the Negev, those living in the West Bank are not Israeli citizens, but since the territory they live in is administered and controlled by the Israeli authorities, Israel has obligations to this community under international human rights and international humanitarian law. However, Bedouin communities have been repeatedly targeted with forcible relocations to poorly serviced townships to accommodate the growth of settlements from the outskirts of East Jerusalem. In May 2018, the Israeli High Court of Justice ruled in favour of the Ministry of Defense’s plan to demolish the entire Bedouin neighbourhood of Khan al-Ahmar Ab al Helu. The Court based the decision on the grounds that the homes had been built illegally under Israeli military law. However, the ruling ignored the fact that it is impossible for Palestinians to obtain permits to build in Area C. The residents were descendants of Bedouin who had been expelled from the Negev in 1953 and had relocated to the area, which at the time belonged to Jordan. Also to be demolished is a school that served about 170 children from five Bedouin communities. The community is near several Israeli settlements on the outskirts of East Jerusalem and stands in the way of a planned major expansion, intended to create a unified settlement area. In October 2018, a ‘peace camp’ comprising Palestinian and Israeli activists managed to block the demolition for some weeks, with the government announcing a postponement. The United Nations (UN), the EU Parliament, and many Israeli and international human rights organizations denounced the demolition plans, stating that if they went ahead, they would constitute a grave breach of international law. Against this backdrop of demolitions and displacement as well as other human rights violations, many Palestinians continue to be subjected to violence and injury by Israeli settlers, with 3 individuals killed between January and October 2018 and around 83 others injured. During that period, the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) recorded 217 incidents of settler violence and vandalism, targeting Palestinians and their properties; 60 of these resulted in casualties. UN OCHA noted that this was the highest level since 2014 and represented a 57 and 175 per cent increase over the figures for 2017 and 2016 respectively. Israeli security personnel generally enabled violent settlers rather than protected Palestinians. Over 85 per cent of investigations into violence committed by settlers against Palestinians are closed without indictments and less than two per cent of complaints submitted by Palestinians against settler attacks result in a conviction – a situation that encourages impunity for the perpetrators and further attacks. Hate crimes by settlers targeting Christian and Muslim Palestinians in the West Bank have also persisted through the practice of so-called ‘price tags’. This consists of acts of random violence and harassment against Christian and Muslim communities, carried out by young settlers. The name ‘price tag’ refers to the price that should allegedly be paid by Palestinians – and also Israelis – who hinder the growth of settlements in the West Bank. While some offenders have been arrested, they are very often released without charges. Throughout the winter and spring of 2019, there were numerous instances of cars owned by Palestinians being vandalised as well as cases of olive trees being chopped down. In addition, the Israeli security forces killed 290 Palestinians, including 55 children, in 2018. 254 people were killed in Gaza, 34 in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and 2 in Israel. The reason for these high casualty figures is the open fire policy of the Israeli military, which includes the use of live ammunition against unarmed demonstrators. There is a climate of impunity with regard to this policy, which is backed by senior figures in the Israeli government and military. A particular focus of the violence has been the Palestinian March of Return protests that repeatedly occurred at the Gaza perimeter fence from the spring of 2018. As a result of the Israeli military’s open fire response, 190 March of Return demonstrators were killed during 2018, including 34 children – three of the victims were only 11 years’ old and one was a 4-year-old. The Israeli military’s use of live ammunition was denounced as deplorable and excessive in April 2018 by then UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein. There have also been a number of individual attacks by Palestinians on Israelis, primarily directed at Israeli security personnel but also in some cases civilians, with stabbings and other incidents concentrated mostly in the West Bank, as well as in and around Hebron and in East Jerusalem. In response, the Israeli security forces have routinely destroyed homes of the families of captured or killed Palestinian assailants in an effort to deter further attacks. But in forcing families to suffer for the actions of relatives, this practice is regarded by rights groups as tantamount to collective punishment and a cause of further cycles of violence.

-

Environment

Palestine currently consists of the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip. The West Bank has a total area of 5,860 km2 and shares borders with Israel and Jordan. The Gaza Strip has a total area of 360 km2 and borders the Mediterranean Sea between Egypt and Israel.

History

Jewish nationalist ideology, Zionism, led to claims on Palestine for the Jewish people. Zionism began in Europe, in reaction to pogroms in the east and assimilation in the west. Early in the 20th century, Zionist leaders began planning for Jewish settlement in Palestine, and the removal of the resident Arab population. After Britain captured Palestine from the Ottomans in 1917, UK Foreign Secretary Balfour made a declaration promising to facilitate the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine. This pledge was enshrined in the UK’s Mandate for Palestine under the League of Nations, which granted to the Jewish Agency the task of Palestine’s economic development.

At the time, Palestine was a highly decentralized village society composed mainly of Sunni Muslims and about ten per cent Christians. Fear of dispossession began to create a sense of national identity, but Palestinian society was ill-prepared to oppose the highly organized and well funded settlement plans of European settlers.

The Holocaust transformed international attitudes towards Palestine by creating substantial sympathy and support for the aspirations of surviving European Jews. In November 1947 the United Nations partitioned Palestine, awarding Jews – who were then only one-third of the population – over half of the territory. Arabs rejected the plan and fighting erupted almost immediately. Jewish forces were better organized and equipped; they quickly prevailed, expelling a majority of the Palestinian population in the process.

Expulsion of the Palestinian population was a premeditated strategy. When Britain withdrew on 15 May 1948, over 200,000 Arabs had already been compelled to abandon their homes. Neighbouring Arab states now entered Palestine but were defeated by the new Jewish state. By the end of hostilities Israel controlled 72 per cent of Palestine, and 750,000 out of approximately 1 million Palestinians had been made refugees. Israel claimed that the refugees had abandoned their homes ‘voluntarily’, refused to allow them back and razed most of their villages. From 1948, refugee camps and communities became a permanent feature of the Arab-held portion of Palestine and neighbouring countries. Egypt administered the Gaza Strip and Jordan annexed the West Bank. The Palestine question destabilized the region.

In 1967 Israel launched a pre-emptive strike against a planned attack by its Arab neighbours, who had the support of other Arab countries. At the end of the Six-Day War, Israel had expanded its borders to include Gaza, parts of Syria, the West Bank, as well as all of East Jerusalem. Israeli forces drove into exile another 300,000 Palestinians and created new sources of Arab resentment that in turn served to propagate Israel’s sense of vulnerability. Egypt and Syria attempted to regain lost territory through a surprise attack in October 1973, but were defeated by the Israeli military. A peace process begun in the wake of the ‘Yom Kippur War’ led to the 1978 Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt that established a framework for peace negotiations and Palestinian self rule in the occupied territories. The Palestinians had formed their own resistance movement beginning in the 1960s, as they began despairing of deliverance by the Arab states. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) conducted a guerrilla war and committed attacks on civilian targets. Civil conflict in Jordan and Lebanon became a by-product of its guerrilla war. In 1982 Israel tried to extirpate the PLO in Lebanon, killing 19,000 people, mainly civilians, in the process. Israel and Egypt signed a formal peace treaty in 1979. Palestinian frustration grew with a weakening of support from Arab countries and culminated in the first intifada (uprising) in the occupied territories from 1987 to 1991.

To consolidate control over the occupied territories, by 1995 Israel progressively expropriated 60 per cent of the West Bank and 40 per cent of the Gaza Strip. It carried out a major settlement programme throughout the territories, designed to retain strategic control and to ring Palestinian population areas. It also illegally annexed East Jerusalem, took total control of all water resources and changed the demographic balance by building massive settlements around the Old City. It changed the body of law regarding the occupied territories with well over 1,000 of its own administrative orders. By stifling economic development in the occupied territories and dumping excess produce on a captive market, Israel made its military occupation profitable. Civil as well as armed resistance was crushed through collective punishment, including curfews, home demolitions and indefinite detention without charge or trial. All these measures violated the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949. Israel denied it was bound by this convention.

The first intifada made occupation costly, but it failed to force Israel out of the territories. The PLO formally recognized the Israeli state in November 1988, hoping it would no longer be treated as an international pariah. It was disappointed. International action to uphold Palestinian rights or secure a just solution remained frustrated by unquestioning American support for Israel and the repeated use of its veto power in the UN Security Council against proposed resolutions that attempted to uphold international law and norms.

A regional peace process launched in Madrid in 1991 led to the 1993 Oslo Accords, signed by Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO leader Yasser Arafat. The Palestinians recognized Israel’s right to exist and Israel agreed to the creation of a Palestinian Authority to govern the occupied territories, the staged withdrawal of Israeli forces, and a process toward establishment of a Palestinian state. One year later, Israel and Jordan concluded a formal peace agreement.

Dissatisfaction with the Accords led a radical right-wing Israeli Jew to massacre a group of Palestinians praying at a mosque in Hebron in 1994 and another to assassinate Rabin in November 1995. Following the Hebron incident, Palestinian militants conducted the first of many suicide bomb attacks on Israeli civilians.

Israeli voters elected a new government in 1996 led by Oslo opponent Binyamin Netanyahu, who pursued the expansion of Jewish settlements in the West Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem. Amid Palestinian suicide attacks on Israel and Israeli military and political provocations, further negotiations between Palestinians and Israelis broke down. A Camp David summit convened by outgoing US President Bill Clinton in July 2000 between Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak (who had been elected in 1999) and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat also failed. That September right-wing Israeli politician Ariel Sharon and other members of his Likud Party paid a highly provocative visit by to the Temple Mount, a site holy to both Judaism and Islam. Surrounded by hundreds of armed guards, Sharon was ostensibly asserting the right of Jews to visit the site. The following day riots erupted in East Jerusalem and the West Bank, and a second intifada began. Increasing resistance to Israeli occupation was met by increased repression and heavy-handed military responses. This in turn elicited greater numbers of terrorist attacks on Israel, which led to even greater military responses, often costing the lives of Palestinian civilians. In 2001 Ariel Sharon became Israeli Prime Minister.

In 2002 Israel re-occupied almost all of the territory abandoned under the Oslo accords and began erecting a separation wall in the West Bank with the stated intent of enhancing its defences against terrorist attacks. By late 2006 it had reached a length of 670 km. But the wall did not follow the boundary between Israel and the West Bank in all places, instead carving off ten per cent of the West Bank to the Israeli side, including Israeli settlements on Palestinian land. In July 2004 the International Court of Justice found that the wall gravely infringed Palestinian rights. 200,000 Palestinians found themselves on the western side of the wall, separated from friends and family in the rest of the West Bank, and subject to strict curfews.

In 2004 and 2005, Israel withdrew all settlers and its forces from the Gaza strip and handed control to the Palestinian Authority. Meanwhile, settlement activity in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, continued. Following the abduction of an Israeli soldier by Palestinian militants and repeated and indiscriminate firing of home-made missiles from the occupied territories into Israel, Israel launched a new military incursion into Gaza in June 2006. Israeli forces bombed Gaza’s only independent power station, and the sustained assault resulted in hundreds of civilian casualties.

Between 27 December 2008 and 18 January 2009, Israel conducted a large-scale military operation in the Gaza Strip, codenamed Operation Cast Lead. According to figures released in September 2009 by B’Tselem, an Israeli human rights organization, the most destructive military assault in Gaza’s history resulted in the deaths of about 1,400 Palestinians, the majority of whom were civilians, and 13 Israelis, including three civilians. The military operation was spurred by rocket attacks against Israeli towns. Israeli air raids and the subsequent ground invasion wrought widespread destruction of Palestinian homes and other civilian infrastructure such as mosques and schools. The military operation followed an 18-month blockade of Gaza’s borders, imposed after Hamas’ takeover of Gaza in mid-2007, which had crippled its economy, leading to unprecedented levels of poverty and hardship among Gaza’s 1.5 million residents – three-quarters of whom were refugees registered with UNRWA. According to a 2009 report by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), 85 per cent of Gaza’s population were entirely dependent on aid as a result of the embargo.

In 2014, following the abduction of three Israeli teenagers who, it later transpired, had been murdered by two members of Hamas, the Gaza Strip was again subjected to a sustained military assault. Over a seven week period in July and August, Israel’s aerial and ground assault against militant groups in the occupied and blockaded Gaza Strip, known as Operation Protective Edge, resulted in the deaths of at least 1,486 Palestinian civilians, including 513 children, and the displacement during the hostilities of around 500,000 people. This was the latest episode in a series of violent escalations in recent years, set against a backdrop defined by unstable progress towards the reconciliation of the two main Palestinian factions, another failed round of US-convened peace talks and unprecedented Israeli settlement expansion in the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem.

Governance

Palestine’s governance is divided between two rival factions, Fatah and Hamas, who respectively control the West Bank and Gaza. The two groups, while both committed to the liberation of Palestine, differ significantly in their approaches. Fatah, since renouncing armed resistance in the 1990s, has engaged in negotiations with Israeli authorities. Hamas, on the other hand, has continued to pursue an armed struggle against the Israeli occupation.

The occupied West Bank is divided into three administrative areas: A, B and C. Area A is under the control and administration of the Palestinian Authority, while Area B is controlled by Israel but administered by the Palestinian Authority. Area C makes up 62 per cent of the West Bank and is under full Israeli military and planning control. 393,000 Palestinians (PCBS, 2017) live in this area, alongside approximately 325,000 Israeli settlers. Minority groups include Bedouin who number around 27,000 people in Area C and 40,000 in the whole of the West Bank. The Israeli government has put aside 70 per cent of the land in Area C for settlements, firing zones, the separation barrier, checkpoints and nature reserves, and this land is therefore ‘off-limits’ to Palestinians.

The Palestinian residents of Area C are especially vulnerable to displacement due to discriminatory planning policies and the threat of violence from groups of religious and nationalist extremists living in neighbouring Israeli settlements. Large swathes of Area C have been designated as nature reserves or closed military areas, where Palestinian construction is forbidden. Additionally, over 6,000 Palestinians live in 38 communities located within Israeli-designated ‘firing zones’ allocated for military training.

The Israeli occupation of the West Bank has been characterized by continuous human rights abuses and violations of international law, in particular in the area of the construction of Jewish settlements in Palestinian territory. These constructions, though illegal, have frequently been facilitated by official Israeli policy. In November 2017, for instance, Israel’s attorney general ruled that private Palestinian land could be appropriated by the state for public settlement – a decision that rights groups fear could be used to retroactively legalize many illegal settlements already constructed in the West Bank.

The Gaza Strip has been governed by Hamas since 2007 with the exception of a short-lived unity government agreed with Fatah in 2014. It is subject to a blockade and harsh sanctions imposed by Israel, termed ‘collective punishment’ and in violation of international law by the UN. In September 2017, Hamas agreed to form a unity government with Fatah and hold elections. As part of a deal brokered between Hamas and Fatah the following month, control over a number of crossings into Egypt and Israel was transferred to Palestinian Authority – although some months later, Gaza residents still complained that they had yet to notice much change in terms of access. The Gaza Strip continues to be overshadowed by the devastation of the 2014 conflict with Israel, exacerbated by Israel’s periodic blockages of the area.

-

Al Haq

Website: www.alhaq.orgB’Tselem

Website: https://www.btselem.org

Institute for Palestine Studies

Website: www.palestine-studies.orgLawyers for Palestinian Human Rights

Website: https://lphr.org.uk

Palestinian Centre for Human Rights

Website: www.pchrgaza.orgPeace Now

Website: http://peacenow.org.il/en/

Updated June 2019

Related content

Latest

View all-

15 April 2024

Enhancing grassroots organizational resilience in a shrinking civic space

Grassroots civil society organizations in the MENA region are excluded from high-level policy spaces and lack sufficient skills to…

-

26 March 2024

MRG warns against escalating violence against Bedouin communities in the West Bank

The Human Rights Council must address the escalating violence against Bedouin communities by Israeli settlers in the West Bank.

-

20 February 2024

MRG and 61 organizations call the UK Parliament to support ceasefire in Gaza

We cannot afford to delay any longer. Private diplomacy and cautious statements are not enough.

Minority stories

-

11 July 2016

State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2016: Focus on culture and heritage

Five organisations from Eastern Europe came together to address the growing concern of online discrimination and hate speech against Europe's biggest minority community, the Roma.

- Central Asia

- Discrimination

- Minority stories

Reports and briefings

View all-

1 July 1998

The Palestinians

In 1918 Christian and Muslim Arabs formed over 90 per cent of the population of Palestine. Fifty years later, those left were a powerless…

-

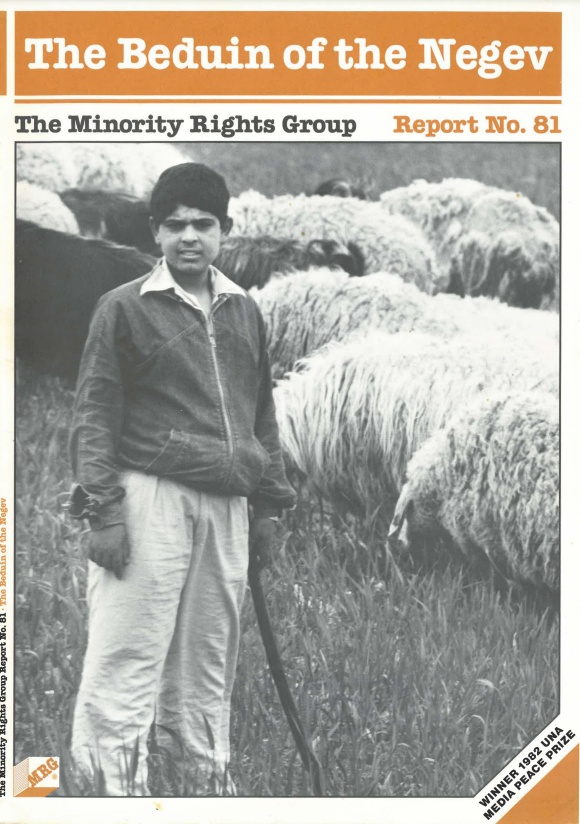

1 January 1990

The Beduin of the Negev

‘Places of bitterness’ was the phrase used by one researcher describing the ‘government settlements’ where the…

Programmes

-

- Middle East (West Asia) (including the Gulf)

- Civil society

Don’t miss out

- Updates to this country profile

- New publications and resources

Receive updates about this country or territory

-

Our strategy

We work with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples to secure their rights and promote understanding between communities.

-

-