Panama

-

Main languages: Spanish, English, Creole, Hakka Chinese, indigenous languages (Buglere, Emberá, Kuna, Ngäbere)

Main religions: Christianity (Roman Catholic, Protestant/Evangelical), indigenous religions, Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Baha’i faith

Main minorities and indigenous peoples: according to the 2010 Census, eight indigenous communities make up 12.3 per cent of the population: Ngäbe (previously Guaymi) 260,058 (62.3 per cent of the total indigenous population) and Buglé (also previously Guaymi) 24,912 (6 per cent of indigenous population); Kuna 80,526 (19.3 per cent of indigenous population); Emberá (Chocó) 31,284 (7.5 per cent of indigenous population) and Wounaan 7,279 (1.7 per cent of indigenous population); Naso/Teribe 4,056 (1.0 per cent of indigenous population); Bokota 1,959 (0.5 per cent of indigenous population); and Bri-Bri 1,068 (0.3 per cent of indigenous population)

Afro-Panamanians were estimated at 313,289 (9.2 per cent) of the population in the 2010 Census. However, data collected by the Institution Nacional de Estadística y Censo (INEC) in 2015 produce a significantly higher estimate of 586,221 (14.9 per cent of the total population). Different studies have suggested this increase is due to greater self-recognition by Afro-Panamanians, alongside more sophisticated measuring methods that allow for greater accuracy in reflecting Panama’s population.

The exact size of the ethnic Chinese population is unknown. While the 2010 Census found that more than 14,000 persons had been born in China, the numbers of ethnic Chinese Panamanians is not known, though some estimates suggest that they comprise around 6 per cent of total population, with as many as a third of the total population potentially having some Chinese ancestry.

The majority of the population of Panama is mestizo, or mixed Spanish, Indian, Chinese and of African descent. Spanish is the official and pervasive language with English being a common second language used by Afro-Caribbean communities and by many in business and the professions. More than half the population lives in the area between Panama City and Colón.

Most of the population of Panama works in the service-based economy, which is supported by ship registration, tourism, banking and other financial services.

-

Panama’s diverse communities, including a sizeable Afro-Panamanian minority, a number of indigenous peoples and an ethnic Chinese population, face a range of issues around discrimination and exclusion. Recent immigrants, many of them from China, India and the Middle East, also face widespread prejudice and barriers to integration. These issues occur in a broader context where the space for civil society in Panama appears to be shrinking in the face of corporate intimidation, particularly around land rights and environmental protections, with activists subjected to judicial harassment and death threats. In addition, sharp economic disparities between rural and urban areas continue to impact on these communities in particular.

The country’s indigenous population are protected by law, with a range of provisions in place to protect their rights and identity, such as bilingual literacy programmes. The majority of indigenous communities reside in one of five semi-autonomous regions known as comarcas, with a number of other traditional indigenous authorities also informally recognized by the government. However, living standards for many residents of the comarcas remain low. According to 2015 World Bank figures, the poverty rate is 6.5 per cent in urban areas, 26.6 per cent in non-indigenous rural areas and 86 per cent in indigenous comarcas. These figures are compounded by limited access to education and health care; the life expectancy of indigenous residents of these territories is 11 years lower than the national average, with maternal mortality rates five times higher for indigenous women than the country as a whole. Indigenous Panamanians also experience discrimination in other areas, such as employment: for example, the majority of labourers in the country’s agricultural plantations are indigenous and frequently work in unsafe, exploitative conditions.

Indigenous communities have also contended with land rights violations, including illegal encroachment by settlers and displacement to accommodate the development of hydroelectric dams, often with little in the way of meaningful consultation. For some, this has resulted in decades of uncertainty. The construction of a dam back in the 1970s, for example, was responsible for uprooting Kuna and Emberá community members from their lands, with the government then failing to provide them with secure land title elsewhere. As a result, they now face the threat of being displaced again as illegal settlers have begun to take over their territory.

Other projects have had a similarly devastating impact on indigenous communities, such as the controversial ‘Barro Blanco’ dam, approved without the free, prior and informed consent of the communities affected. Though in September 2016 members of the Ngäbe-Buglé General Congress rejected the planned completion of the dam, Panama’s Supreme Court subsequently ruled in favour of the project. Since then, with the flooding of the river, much of the crops cultivated by Ngäbe-Buglé communities have been destroyed. In May 2018, the Tabasará River was drained for maintenance work, wiping out local fish stocks and leaving Ngäbé-Buglé communities with no source of protein.

The Afro-Panamanian community faces similar issues including economic marginalization, lack of political representation and regular discrimination in everyday life, with some employers reportedly favouring lighter-skinned candidates, especially for senior level or high-profile positions. Though the community has been very active in recent years in campaigning for greater recognition, with the government having implemented a number of inclusive measures such as the creation of the National Secretariat for the Development of Afro-Panamanians (SENADAP) in 2016, Afro-Panamanians still struggle with wider social marginalization.

Panama’s Chinese community has experienced a long history of racism that persists to this day. The government has undertaken a number of positive measures, including the creation of a consultative body, the National Council on the Chinese Ethnic Group, to promote development and integration. Nevertheless, tensions around continued immigration from China, much of it undocumented, has contributed to anti-Chinese sentiment directed at both recent migrants and Panamanian citizens of Chinese ethnicity.

LGBTQ+ groups in Panama still face harassment and discrimination, and while Panamanian law does forbid discrimination against individuals with HIV/AIDS in employment and education, this is often not enforced in practice. This holds particularly true for indigenous peoples, who experience the highest level of negative attitudes when living with HIV/AIDS (77.8 per cent for women and 76.9 per cent for men) compared to non-indigenous Panamanians (42.6 per cent for women and 45.2 per cent for men). At the same time, contraceptive protection is also harder to access, with 50.2 per cent of indigenous women and 20.9 per cent of indigenous men without a condom when they needed it compared to 18.1 per cent of non-indigenous women and 3.7 of non-indigenous men. As a result, levels of infection are especially high in some communities: for instance, HIV/AIDS is the second largest killer for Ngäbe-Buglé members.

-

Environment

The Republic of Panama is located on the Isthmus of Panama, which connects Central and South America. On the western border is Costa Rica and on the east is Colombia. The Panama Canal runs between the low-lying Caribbean and Pacific Coasts. There are numerous offshore islands.

The total population numbers around 4 million and is one of the smallest in Spanish-speaking Latin America.

History

Before the arrival of the Spanish in 1501, Panama was densely inhabited by a number of indigenous peoples whose kinship groups extended into the Caribbean as well as South America and along the Isthmus as far north as Honduras. Craftsmanship was highly skilled, for instance in the making of gold huacas or figurines which were traded north with Mayan cultures in Mexico and south into Colombia. Trade and travel between the Pacific and Caribbean coasts were conducted along a trail established by the indigenous nations. The trail was later adapted and used by the Spanish, who named it ‘Las Cruces’.

As the narrowest part of the American continent, Panama’s history has been largely determined by its strategic importance for imperial powers. Following the Spanish arrival the Isthmus became a major crossroads for intercontinental and transoceanic travel using the Camino Real (Royal Road), which developed out of the original Las Cruces trail. For nearly two centuries it was the principal route for taking large numbers of enslaved Africans to the Pacific Coast colonies like Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia, and for transferring gold and silver from South American mines to Spain.

Today mestizos of mixed indigenous, African and European ancestry make up the majority of the local population.

With the decline of the Spanish Empire, Panama lost much of its importance and became a part of independent Colombia in 1821. Its significance as a transit area was enhanced again when US prospectors and settlers began making their way to Oregon and the goldfields of California via the Isthmus of Panama.

In 1846, the government of Colombia signed a treaty with the United States permitting the construction of a railroad across the territory that would run from Panama City on the Pacific to Colón on the Caribbean Coast. In addition to Chinese workers this brought the first influx of Afro-Caribbean labour migrants who were recruited from Jamaica and other parts of the British West Indies.

In 1903, the United States supported the secession of Panama from Colombia in order to gain control over the Canal Zone: an eight-kilometre strip of land, on either side of the construction site of the proposed inter-oceanic canal. In exchange for a US guarantee of Panamanian freedom from reincorporation into Colombia, the new state granted the US the right to build and own the canal ‘in perpetuity’. The construction employed over 30,000 Afro-Caribbean ‘diggers’, many of whom stayed after completion. The Canal was opened in 1914 and US involvement in the creation of Panama set a precedent for regular interference in Panamanian affairs.

In 1939, the country’s protectorate status was ended in a revision of the Canal Treaty which explicitly recognized Panamanian sovereignty. This ushered in an era of ultra-nationalism which had a negative effect on non-Hispanic groups however, while the USA continued to control the Canal Zone. It was not until the 1970s, under the government of Omar Torrijos, that a new form of Panamanian nationalism and a desire for sovereignty brought Afro-Panamanians and the dominant mestizo Spanish-speakers together. A concrete result of this process was the revision of the canal treaty in 1977, which gave Panama sovereignty over the Canal Zone and affirmed that full operational control would pass into Panamanian hands in December 1999.

The US removal of Panamanian leader General Manuel Noriega, through a military operation in December 1989 marked a blow to Panamanian sovereignty and a return to a period of US interference in the country’s affairs. More than 2,000 died, many more ‘disappeared’ and 20,000 lost their homes during the first days of the invasion.

After the invasion, Panamanian political parties became more cautious about promoting anti-US nationalism. The 1994 elections were won by Ernesto Balladares and the Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD) which was the party of Noriega. The new government toned down the party’s previous anti-US views and focused on trying to attract more investment and expansion of the economic sector.

In the elections of September 2004 Martín Torrijos (son of Omar Torrijos) of the PRD earned 47 per cent of the vote and assumed a five-year presidential term. Government policies continued to favour a market economy and free-trade arrangements with the United States.

In May 2009 Panama held general elections in which Panamanians voted for all their elected leaders, from President through National Assembly Deputies to city councilmen and mayors for a five-year term. Ricardo Martinelli from the Democratic Change party, founded in 1998, won the election with 60 per cent of the vote. Martinelli’s government implemented a number of projects during his rule that impacted severely on indigenous communities in the country. This included the outright dismissal of a petition by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to suspend a US$600 million hydroelectric project in the Bocas del Toro province. Subsequently completed in 2011, this particularly affected the Ngäbe-Buglé community, displacing many from their homes. Martinelli’s government approved similar projects such as the ‘Barro Blanco’ dam in the same year, which is still ongoing and has caused severe inundations, mass fish killings and destroyed the crops upon which the Ngäbe-Buglé community relies.

In May 2014, Juan Carlos Varela Rodriguez, candidate of the opposition People First Alliance, was elected as President. Martinelli was constitutionally barred from seeking a second term in office, and was subsequently implicated in allegations of public embezzlement and wire-tapping. Carlos Varela’s government, on the other hand, has shown some positive initiatives towards indigenous peoples and minorities in the country. Examples include the establishment of political guidelines and a plan of inclusion for Afro-Panamanians, approved by the General Assembly in 2014. Furthermore, in 2016 the National Secretariat for the Development of Afro-Panamanians (SENADAP) was established. The Ministry of Social Development also created the National Council on the Chinese Ethnic Group as a consultative body in 2015.

Despite these positive steps, hazardous hydroelectric projects, deforestation, poverty, health, illiteracy and other issues particularly affecting minorities and indigenous people persist. Corruption remained a key political issue for the May 2019 presidential elections, which resulted in victory for the Democratic Revolutionary Change Party candidate Laurentino ‘Nito’ Cortizo, who is seen as a centrist and ran on a platform of combatting inequality.

Governance

Panama’s Constitution seeks to protect the ethnic identity and native languages of Panama’s population, requiring the government to provide bilingual literacy programmes in indigenous communities. The Family Code recognizes traditional indigenous cultural marriage rites as the equivalent of a civil ceremony. The Ministry of Government and Justice maintains a Directorate of Indigenous Policy and the Legislative Assembly also has an indigenous affairs commission, which is aimed at addressing charges that the government has neglected indigenous needs.

Despite legal protection and formal equality, indigenous peoples without exception have relatively higher levels of poverty, disease, malnutrition, and illiteracy than the rest of the population. The biggest campaigning issue for Panama’s indigenous peoples has been the struggle for land rights in the form of autonomous land reserves.

The 1972 Constitution required the government to establish comarcas or reserves for indigenous communities, but this policy was not universally implemented. The country has demarcated territories for five of the country’s indigenous peoples. These have a significant degree of autonomy and are free from taxation.

In November 1993, following a successful national strike with the support of other social movements, the National Coordination Body of Indigenous Peoples of Panama, made up of Kuna, Emberá and Ngäbe-Buglé leaders, sponsored a national convention to demand the creation of a high-level government commission to implement greater investment in indigenous areas.

President Endara endorsed the proposals and incorporated the Convention on the Indigenous Peoples’ Development Fund into domestic law. These were important steps; however, the Ngäbe-Buglé experience of fighting the mining concessions showed that the government would only allow the participation of indigenous communities in decision-making is when it is forced to by civil protests.

-

General

Centro Para la Conservación y el Desarrollo Alternativo Indígeno

Website: http://cicada.world

Centro de la Mujer Panameña

Website: https://www.centromujerpanama.org/

Coordinadora Nacional de los Pueblos Indigenas de Panamá

Website: http://coonapippanama.org/

The Society of Friends of the West Indian Museum of Panama

Website: http://www.samaap.org/

The Silver People Heritage Foundation

Website: http://thesilverpeopleheritagefoundation.org/

Centro de Capacitación Social de Panama

Website: https://www.fidh.org/organisation/centro-de-capacitacion-social-ccs?lang=en

Centro de Estudios y Acción Social Panameña (CEASPA)

Website: http://www.propuesta5.canalvirtual.com/

Forest Peoples Programme- Fundación para la Promoción del Conocimiento Indígena (FPCI)

Website: https://www.forestpeoples.org/es/partner/fundacion-para-la-promocion-del-conocimiento-indigena-fpci

Ministerio de Obras Públicas (MOP)

Website: http://www.mop.gob.pa/

UNDP Regional Hub in Panama

Institute on Race, Equality, and Human Rights – Panama

Website: http://raceandequality.org/panama/

Afro-Panamanians

Coordinadora Nacional de las Organizaciones Negras Panameñas

Website: http://diadelaetnia.homestead.com/coordinadora.html

Centro de la Mujer Panameña

Website: https://www.centromujerpanama.org/The Society of Friends of the West Indian Museum of Panama (SAMAAP)

Website: http://samaap.com/The Silver People Heritage Foundation

Website: http://thesilverpeopleheritagefoundation.org/Ngäbe-Buglé

Asociaciόn de Mujeres Ngobe

Website: https://www.facebook.com/asmung.pa/

Meri Ngobe-Mujeres de Sandubidi (Popa 2)

Website: http://www.meringobe.bocasdeltoro.org/ingles/indexing.html

Ngobe Bugle Un Future Sostenible

Website: https://www.ngobebugle.org/

Kuna

Congreso General de la Cultura Kuna

Website: http://onmaked.nativeweb.org/

Movimiento de la Juventud Kuna

Website: https://orgs.tigweb.org/movimiento-de-la-juventud-kuna

Emberá and Wounaan (Chocó)

Organizaciόn de Jόvenes Emberá y Wounaan de Panamá (OJEWP)

Website: http://www.ojewp.org/

Chinese Panamanians

Centro Cultural Chino Panameño

Website: https://www.ccchp-isys.edu.pa/

Asociación de Profesionales Chino-Panameña

Website: http://aprochipa.org/

Updated May 2020

Related content

Reports and briefings

View all-

1 June 1995

No Longer Invisible: Afro-Latin Americans Today

The distinct but extraordinarily diverse ethnic and cultural identities of Afro-Latin Americans have received little official recognition….

-

1 July 1987

The Amerindians of South America

For over 20,000 years a wealth of many cultures flourished in South America, both in the high Andean mountains and the lowland jungles and…

-

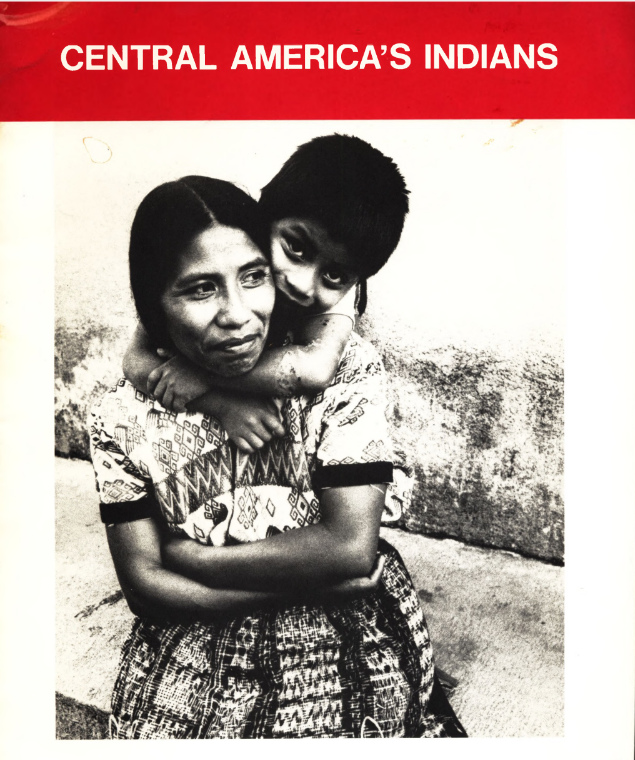

1 April 1984

Central America’s Indians

In Latin America today we find one of the largest remnants of colonialism in the world. The concept “Indian” itself is, of course, a…

Don’t miss out

- Updates to this country profile

- New publications and resources

Receive updates about this country or territory

-

Our strategy

We work with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples to secure their rights and promote understanding between communities.

-

-