50 years of Minority Rights Group

The chapters

This collection of essays draws on the many strands that characterize our work across this time period.

- 01

Introduction

The best qualities of humanity have, throughout history, attracted individuals of high calibre to step beyond their comfortable worlds to reach out in support and assistance to others. Their actions, born out of kindness and empathy, and…

0 min read

- 02

David Astor remembered: ‘MRG could not have dreamt up a more perfect champion’

By Shaun Johnson A book on my shelf that I especially treasure is titled David Astor and the Observer (David Astor was Editor of the Observer from 1948 to 1975). In it, the biographer Richard Cockett gives a fine account of the sweeping and…

0 min read

- 03

Reaching the most marginalized: an intersectional approach to minority rights

By Nicole Girard The mandate of MRG has changed and evolved over the past couple of decades as the organization has redefined its approach to minority rights. Consistent throughout these changes, however, is the effort to realize the rights of…

0 min read

- 04

Sri Lanka: using arts and poetry to confront the legacy of conflict for minority women

By Nicole Girard MRG became involved with Tamils in Sri Lanka with our first report in the 1970s, with regular updates thereafter. By the time Neelan Tiruchelvam joined MRG’s International Council in 1994, MRG was establishing a South Asia…

0 min read

- 05

Ensuring accessible education

By Claire Thomas Although human rights in essence date back centuries, if not millennia, human rights as a movement really began to take off in the 1960s and 1970s. MRG’s birth was therefore at a moment when many like-minded groups were…

0 min read

- 06

United Kingdom: The Voices project – a unique platform for refugee children to share their storie

By Rachel Warner Voices was a series of dual-language booklets of autobiographical writing by young asylum seekers and refugees in London schools, published by MRG in the 1990s, to meet a growing need for materials that reflected the…

0 min read

- 07

Addressing health inequalities

From the beginning, MRG has systematically focused on health services and the barriers that minorities and indigenous peoples face in accessing them. The disparities, while often overlooked, are striking: where statistics are available, health…

0 min read

- 08

Kenya: To identify discrimination, we first need to get the data – health inequalities among Somali women in Mandera County, Kenya

By Claire Thomas A recent and ongoing example of MRG’s work on health focuses on minority and indigenous women in Cambodia, Ethiopia, Kenya and Myanmar and their right to equally access sexual and reproductive health services such as…

0 min read

- 09

Making voices heard at the international level

By Neil Clarke MRG’s work with the UN has been one of the cornerstones of its work and identity over the last 50 years. The organization’s profile as the leading international non-governmental organization (NGO) in the field of minority…

0 min read

- 10

Supporting the creation of a new UN minority issues mandate

By Evelin Verhás By the early 2000s, the indigenous peoples’ rights movement had successfully achieved the creation of several UN mechanisms devoted to indigenous issues, including a Working Group, a Permanent Forum and a Special…

0 min read

- 11

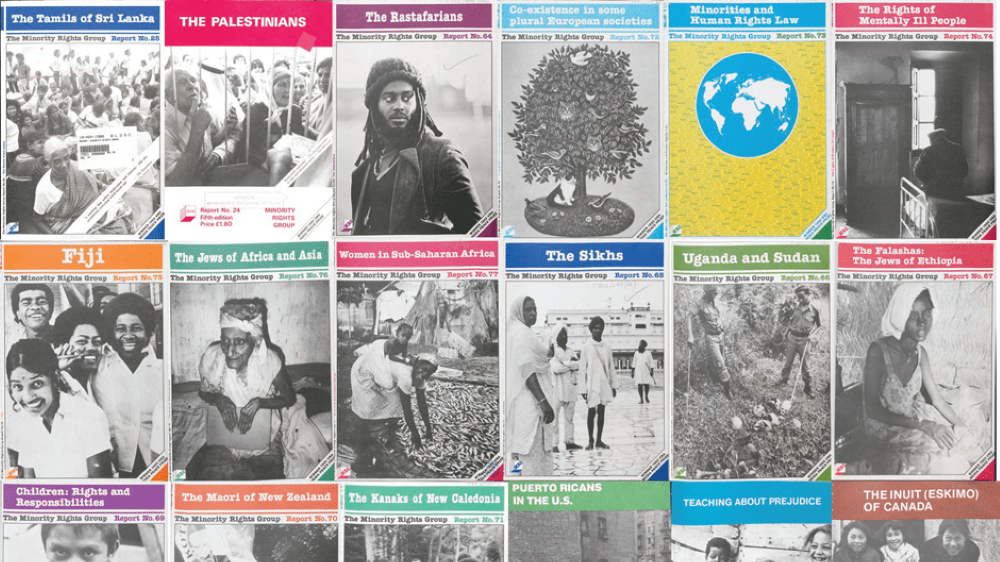

Making minorities and indigenous peoples visible: the role of MRG’s research and publications

By Peter Grant In 1970, shortly after our foundation, MRG launched our first publication: Religious Minorities in the Soviet Union. This was followed shortly after by other reports, ranging from the situation of Aboriginal Australians and that…

1 min read

- 12

The World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples

By Alan Phillips The year 1989 was a watershed for minority rights in Europe. The tearing down of the Berlin Wall in Germany symbolized the rejection of the Communist system by the people of Central and Eastern Europe. Although MRG was a very…

0 min read

- 13

Challenging colonial legacies: Minorities and indigenous peoples’ struggle for inclusion in Africa

By Hamimu Masudi The dubious origins of statehood in Africa have been clear to anyone interested in understanding and explaining contemporary development challenges on the continent. By the stroke of a pen at a Berlin conference in 1884, the…

0 min read

- 14

Capacity-building for minority and indigenous leadership

By Chris Chapman Providing support to minority and indigenous representatives has always been a central part of the MRG ethos. For many years the organization has been running training workshops for activists, first in Geneva and Strasbourg,…

1 min read

- 15

Mauritania: ‘I saw that the system was unjust – it strengthened my resolve to combat injustice’

By Chris Chapman Salimata Lam has been an activist all of her adult life, since joining a pro-democracy movement in her teens. In the 1980s, she was even deported from the country for three years and stripped of her citizenship, which only made…

1 min read

- 16

Adapting to new crises: Meeting the challenge of Covid-19

By Rasha Al Saba From conflict to climate change, MRG has repeatedly reoriented its work in the face of new crises to ensure that minorities and indigenous peoples – frequently the most affected by these challenges – are not forgotten. Most…

1 min read

- 17

Challenging hate: The struggle for the rights of Roma

By Neil Clarke Numbering at least 10 million, though the actual numbers are likely higher, Roma make up the largest ethnic minority in Europe. Roma populations can be found in every country and, while it would be wrong to perpetuate the image…

0 min read

- 18

Dominican Republic: Using film to tell the story of Dominicans of Haitian descent

By Sofia Olins When I first met Rosa Iris, she was completing her law degree while raising her 6-year-old son alone. This, in the compromised conditions of a bateye (a town of corrugated shacks with no water and electricity), is no easy…

0 min read

- 19

Iraq and Syria: Documenting human rights violations in conflict – the Ceasefire online reporting tool

By Miriam Puttick In conflict zones around the world, violations against minorities are often an inseparable element of the core conflict dynamics. States and armed groups will often harness long-standing tensions and stoke hatred against…

0 min read

- 20

Iraq: ‘We need real and effective political and economic participation – it should not be décor’

By Chris Chapman Mikhael Benjamin is an Assyrian-Christian activist from Iraq who has devoted his life to fighting for the rights of his community, first in a political party, and since 2005 in the human rights movement. Since the beginning…

0 min read

- 21

Kenya: ‘The Ogiek journey in the corridors of justice, from Kenya to Banjul then Arusha, was never a bed of roses, it had ups and downs, but thanks to MRG’s support throughout, the litigation process was a success’

By Lucy Claridge In 2017, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights issued its first ever ruling on indigenous rights in a case brought by MRG in partnership with Kenya’s Ogiek community. Numbering around 30,000 people,…

1 min read

- 22

Litigating indigenous land rights: a model for conservation

By Lucy Claridge MRG’s strategic litigation programme was established in 2002, in response to the clear need for specific legal tools to combat violations of the rights of minority and indigenous communities throughout the world. It aims to…

0 min read

- 23

Managing and preventing conflict: a minority rights-based approach

By Chris Chapman From the outset in 1970, MRG reported on many areas of violent conflict where the rights of minorities and indigenous peoples were denied and where others remained silent for fear of being associated with secessionists or…

0 min read

- 24

Pakistan: Pragmatism or idealism? Advocating against blasphemy laws

By MRG’s former Head of Programmes In my time at MRG, we worked on numerous programmes on Freedom of Religion or Belief (FoRB). We advocated for an end to the death penalty for apostasy in Mauritania. In India and Bangladesh, we…

0 min read

- 25

Protecting and promoting the rights of religious minorities: an evolving approach

By Silvia Quattrini Freedom of Religion or Belief (FoRB) is usually defined as the freedom to adopt, change or renounce a religion or belief and it involves principles such as freedom of worship and freedom from coercion. Unnecessary…

0 min read

- 26

The power of innovation to create lasting change

By Claire Thomas MRG is not an organization that has set out to be innovative for its own sake: however, it is an organization that listens hard to the people whose interests it exists to serve. And this commitment to listening to the…

0 min read

- 27

Ukraine: Empowering civil society to turn the tide of anti-Roma hate crime

By Yulian Kondur Hate crime has become an increasingly pressing issue in Ukrainian society, particularly since the beginning of 2018, when the number of attacks on representatives of the Roma community and LGBT+ groups has risen. Violence was…

0 min read

-

The best qualities of humanity have, throughout history, attracted individuals of high calibre to step beyond their comfortable worlds to reach out in support and assistance to others. Their actions, born out of kindness and empathy, and extolled in countless stories and exhorted for centuries by philosophers and faith leaders, led them to stand up for the oppressed, while seeking to amplify their voices and do what they can to safeguard those far from sites of power against their oppressors.

Minority Rights Group International (MRG) owes its existence to this tradition. In the days when David Astor imagined the need for such an organization it was clear that there were people ‘with voice’ and those with none. It was a period of hope, but old fears loomed not far away. Decolonization had freed vast swathes of territories from colonial rule, the devastation of the Second World War was in the rear-view mirror, and fledgling African and Asian states were beginning to take their places on the world stage. However, stories of ethnic violence and unrest were never far from the surface, whether rooted in recent history – the reappearance of anti-Semitic graffiti in European streets, for instance – or new developments, such as the arrival of African and Asian families in search of work whose experiences of stigma and discrimination continue to echo generations later. Giving voice to the voiceless may well have been a theme that motivated and drove our predecessors at MRG, sustained by a belief that research, insight and reason would enable conversations about truth to power that would ultimately prompt lasting change. Written into this was the assumption of the good in the human spirit: that empathy with humanity would win the day.

It is beyond any doubt that MRG was born of privilege. Its early pace-setters chose to use that privilege as a platform to argue, reason and negotiate with those in power with the specific purpose of achieving significant administrative, legislative and judicial changes that would ensure the realization of the inherent dignity and worth of every individual from a minority or indigenous background. Located in London, the capital city of one of the modern world’s most notorious colonial powers, the United Kingdom, it sought to use its place at the table to argue for those not invited to attend.

Fifty years is a very long time for an organization of the size and complexity of MRG. This collection of essays draws on the many strands that characterize our work across this time period, written by some of the incredible people who worked and continue to work for us. In the initial phases much of this work probably sought to ‘give voice to the voiceless’. Looking back at our earliest reports, it is clear that our predecessors drew attention to minorities and indigenous peoples whose issues had not received much, if any, world attention. The impact this had – the simple act of public recognition for communities who were sometimes not even officially acknowledged by their own governments – should not be underestimated: time and again, we hear from now elderly minority and indigenous activists who contact us to say that an early MRG report was instrumental in their own rights awareness.

Two Lisu girls in Shan State, Myanmar / Jenny Matthews/Alamy. But the more we have listened, learnt from and grown in our admiration of the communities we partner and struggle with, the more we have realized our own implication in a deeply unjust international society and sought to, instead, refocus our efforts on disrupting, fixing and reconstructing sound systems to tune out the ambient noise that continues to silence the voices of minority and indigenous communities. This requires, of course, the courage not only to call out the abuses of governments, corporations and armed groups, but to also reflect on our own positionality in the power structures that serve to exclude and marginalize these groups.

Minority rights is one of the oldest antecedents to the development of the Law of Nations. Its prevalence in the earliest treaties and agreements signed between states was far greater than principles of human rights law. Yet power and privilege over centuries ensured that it stayed in the margins, called on at key moments to present a civilizing hue to naked quests for power and domination that sought to subjugate all who presented themselves as obstacles. Minorities and indigenous peoples never self-defined themselves that way, nor specifically sought to stand in anyone else’s way. We merely became ‘minorities’ and ‘indigenous peoples’ as others sought to harness what we had and sought to rally their greater numbers in a bid to revoke rights through the exercise of force and subterfuge.

The human rights framework that emerged most strongly with the creation of the United Nations (UN) appeared to have finally found a way to guarantee the rights of all. In the centuries-old legal battle between Order and Justice, almost always won by Order even when it meant imposing an unjust order, it instead emphasized the notion of Justice. However, at its very foundations the minority experience was relegated from the human rights headlines, despite the specific experience of Jews and others as minorities targeted by genocidal actions, that led to the key moments in the founding of the organization. The task adopted then, especially relevant in today’s troubled times, was that rather than emphasizing that minorities’ lives matter, it was important instead to guarantee that all lives mattered. The key difference, then as now, is that one calls for structural change, the other is merely a statement of an obvious value.

For indigenous peoples, a different equally promising dawn appeared. High on the UN priority list was the celebration of the notion of self-determination, accompanied by stirring words against oppressive colonial rule. In many cases, however, the processes that flowed from this principle merely transferred power from white colonial rulers to men from dominant ethnic, religious or linguistic communities, often aligned closely with power and speaking its language, to start a reign of a different hue.

So here we stand – more than 50 years later in 2020, in the midst of a pandemic that has disproportionately affected minorities and indigenous peoples. The failure to create inclusive societies has simply meant that ever more mediocre men from dominant majorities can ascend to power. Hate has been decimating our societies, dividing us into narrow vote banks, fostering artificial ‘majorities’ as desperate despots keen to seize levers of power, with neither the vision nor the solutions to societies’ many problems, utilize the obvious: large numbers trump small numbers.

The quest for democratic governance has turned into a simple game of numbers far removed from the hallowed values that underpinned its birth. The generation of these is achieved through complicated algorithms that use personal identity data available to a select group of corporations. This facilitates the construction of complex formulas to ensure that scapegoating of opponents can, through a calculated reach that includes a toxic mix of hate speech, fake news and intimidation, result in influencing individual voter decisions. These mechanisms disseminated en masse, targeted to an angry disenfranchised public faced with a sense of crisis and the drying up of economic opportunity, has created our distasteful dissonant present. The state of disrepair in public life, especially the conspicuous lack of governance abilities among many of those supposedly responsible for governing, has been deeply exposed by the recent outbreak of the pandemic. Global society today has effectively reached a fork in the road.

The perpetrators of hate politics who drive narrow conceptions of identity to scaremonger have, unsurprisingly, proven unable to deal with real threats. These include the steady decline in the ability to generate meaningful employment for gainful return, apathy and indifference towards the emerging devastation of the climate crisis and, of course, more dramatically, failures to control the spread and potency of the pandemic that has decimated societies. Those divisive formulas that won power, ostensibly in the name of the majorities, failed to evoke a response that could safeguard life, generate standards of living, or come to terms with the problematic histories that led to the call for #BlackLivesMatter.

The result is a loss of authority and respect for governance, tokenistic actions regarding the climate crisis, and eye-watering death tolls as individuals without the requisite governance experience find themselves out of their depth, but are not endowed with the spirit or courage to resign in realization of their own limitations. Rather they have decided to ‘fight back’: stirring more hate, deflecting blame while continuing to drive humanity towards disaster by inaction and ineptitude, ensuring only that they squeeze out profit for their wealthy friends with insatiable appetites.

This caricature of some democracies stands in sharp contrast to others. Covid-19 has served as a testing ground for the democratic health of many countries, particularly their ability to prioritize the safety and well-being of all their citizens regardless of religion, language or ethnicity. Societies that invested in generating and reconstructing an inclusive national fabric have facilitated the development of the collective talent present in the entirety of its society. These states, led by individuals (often women), listened to the unfolding crises carefully and hastened to ensure the pandemic would not spread. They did not worry about identities and entitlements, nor seek to construct bluffs or displays of bravado, resorting instead to long hours of meticulous planning to ensure that the entirety of their populations would come through the crisis. They realized the virus would not discriminate and put in place measures to ensure safety and security especially for the vulnerable, conscious that leaving the virus festering among subaltern communities would be not only morally dubious, it would effectively prolong the economic crisis that will inevitably follow to hinder compete eradication.

In many ways, the pandemic has brought to light many long-standing issues such as exclusion, inequality and invisibility that were already recognized in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with their emphasis on ‘leaving no one behind’. These are the key challenges for minority and indigenous rights in the next few decades, even once the devastation of the current pandemic has passed. While Covid-19 may become the defining crisis of the early twenty-first century, it looms against the larger, more entrenched environmental crisis: this, like the virus, is already impacting disproportionately on minorities and indigenous peoples.

The SDGs call for urgent action at scale in addressing planetary issues such as climate change through reducing consumption and reversing damage, while seeking solutions to benefit life in its entirety on the planet, including the seas; they focus on ensuring that people-oriented benefits – the end of poverty, equitable access to health, education and sustained work – accrue to all, with none left behind; and they outline a range of processes, including the active reduction of inequality, the elimination of gender disparity, and the entrenching of global solidarity and institutions to harness cooperation in achieving this vision.

The message for us at MRG is clear: we need to work actively in cooperation with others to out-think and out-manoeuvre the bullies that lurk ready to seize opportunities to enrich themselves, while actively designing solutions and systems that invest in the people that can replace them. One option saves lives here and now. The other is focused on winning the future in such a manner as to make the angry men irrelevant. Most crucially, this has to be done by educating majorities, schooling them in the ways of empathy – the same foundational value that led the smartest and hardiest to reach out beyond their worlds to others. This time we do not need saviours at high table, just the collective power and determination of the many, to imagine and implement solutions for a world where differentiated human identities are a source of celebration, not a red line between existence and annihilation.

Top photo: An elderly Nyangatom man in Omo valley, Ethiopia / Alamy

-

By Shaun Johnson

A book on my shelf that I especially treasure is titled David Astor and the Observer (David Astor was Editor of the Observer from 1948 to 1975). In it, the biographer Richard Cockett gives a fine account of the sweeping and significant life that was that of David Astor.

But the reason for my treasuring the 1991 edition above all is to do with the subject rather than the authorship. For David, in his elegantly evolved but characteristically somewhat diffident hand, had inscribed it thus at the time:

To Shaun

With thanks for getting me interested in politics again.

Yours, David

It is no secret among us legions of admirers and beneficiaries that David did, indeed, in later life get disillusioned and feel hopeless about what he often described to me as humans’ limitless ability to deceive themselves about their own actions in the services of right and wrong.

But how was it that I had the inestimable privilege of helping to get the great man reinvolved after a period of downcast withdrawal? In the mid-1980s he took me in to his home in Cavendish Avenue, St John’s Wood, after my time at Oxford ended and I contemplated the frightening prospect of going home to the fists and flames of my beloved, benighted South Africa. My country was then experiencing States of Emergency in what were (though we of course could not know it) the dying days of apartheid. He became fascinated once again by South Africa, with which he had been significantly engaged but had never visited.

David’s great friend Anthony Sampson, who had in fact introduced us, published a Festschrift in which this account was given:

In October 1986 David and Bridget spent a month in South Africa – his first visit to the country in which he and the Observer had been so long and intimately involved. They criss-crossed the country seeing famous anti-apartheid leaders on a State of Emergency tour planned and guided by Shaun Johnson, a young academic, writer and activist whom David had taken under his wing when he was studying in England on a Rhodes Scholarship, and who now worked on the Weekly Mail.

It was on this trip that I learnt of David’s seminal support for Minority Rights Group (MRG). I took him and Bridget to Durban to see his old friend and protégé Laurence Gandar, who had edited the now-defunct liberal Rand Daily Mail from 1957 to 1969 and who, after being sacked for alienating many of his white readers, moved to London (with David’s assistance) and became the first director of MRG. It was fascinating, all these years later, to listen to them reminisce about the early days of MRG.

David collected seemingly random causes, but in their globally far-flung range, you could always divine his logic when you worked out that in there someone, somewhere, somehow, was being done down unfairly. And when David Astor became convinced that someone somewhere was being done down, it was his unstoppable instinct to Somehow Do Something About It. MRG could not have dreamt up a more perfect champion and midwife if it tried.

Richard Cockett situates MRG in David’s body of works thus:

A practical illustration of David’s impartiality was the formation of the Minority Rights Group in 1961, an organization formed largely by him and Michael Scott to publicize the cause of oppressed minorities in the post-colonial world. The first director was Laurence Gandar. Others involved were Ronald Oliver, the Africa expert, and David Kessler, editor of the Jewish Chronicle. The Minority Rights Group produced studies of the plight of ethnic or national minority communities, whether they be Kurds, Palestinians or Eritreans…. The fight for the classic liberal causes of political rights and freedom thus extended from white colonial to post-colonial African or Asian rule.

Jeremy Lewis recorded the catalytic factors behind the establishment of MRG:

The Minority Rights Group stemmed from David’s and Michael Scott’s support for the Nagas, and reflected, in part, their belief that – in David’s words – ‘the United Nations, being an organization of governments, is a particularly inhospitable forum for the rights of minorities.’ Once again, it began life with a lunch…, attended by David, Michael Scott, Guy Wint and Conor Cruise O’Brien in 1962; David told Keith Kyle that it was set up ‘to act as a friend, adviser and introducer of minorities, without becoming their propagandist’.

David’s involvement in MRG lessened over time but in all the years I spent with or near him, he made it clear that it was one among his many initiatives of which he felt most proud. It is an honour for me to add these small recollections to this valuable volume, which David would have much enjoyed while habitually pooh-poohing his own contribution. That was David.

—

Shaun Johnson was Founding Executive Director of The Mandela Rhodes Foundation from 2003 to 2019. Besides being a renowned anti-apartheid journalist, he was also an internationally awarded author: his works include: Strange Days Indeed, the bestselling book on South Africa’s transition introduced by Nelson Mandela, and the novel The Native Commissioner, winner of numerous accolades including the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best Book in Africa. The Leverhulme Mandela Rhodes Doctoral Scholarship has been renamed the Shaun Johnson Memorial Scholarship in honour of his legacy.

Johnson passed away in February 2020. He wrote this personal recollection of his friend David Astor, MRG’s founder, just months before he died.

Photo: David Astor

-

By Nicole Girard

The mandate of MRG has changed and evolved over the past couple of decades as the organization has redefined its approach to minority rights. Consistent throughout these changes, however, is the effort to realize the rights of the world’s most vulnerable. Yet our thinking on which groups constitute the most marginalized and how we reach them has come a long way since our inception.

The concept of ‘intersectional discrimination’ is now key to our work. In order to reach the most excluded groups, we have to understand how discrimination intersects on different axes of identity – for example, gender, sexuality, age, race, religion and disability. These are not experienced independently of one another, but together compound the experience of discrimination in the lived reality of a particular individual.

This understanding of discrimination, however, was not widely prevalent in the international human rights community until perhaps the early 2000s, and is still overlooked today. The Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) does not include specific mention of how women’s experience of discrimination may be compounded on the basis of race or religion, for example. CEDAW, though ground-breaking, prioritized a ‘shared experience’ of gender-based discrimination that relegated consideration of race and other forms of intersectional discrimination to its margins.

A Tamil woman in Sri Lanka. MRG also struggled with incorporating intersectional thinking into our work. Some of our reports from the 1970s focused on women in specific regions of the world, such as Women in Sub-Saharan Africa, but did not in fact address minority women in particular, yet the reports were revolutionary in even considering the distinct experience of women from what was then commonly described as the ‘Third World’. So too our 1980 report on female genital mutilation (FGM) was published only one year after CEDAW came into force, at a time when the practice was largely unknown to an international audience and the dialogue surrounding the practice was frequently sensationalist and sometimes racist too. Yet the report did not analyse any specific factors of intersectional dimensions that might be at play.

‘Essentially, our predecessors were feeling that what they were doing was shining a spotlight on marginalized groups more generally,’ explains Carl Söderbergh, MRG’s Director of Policy and Communications. ‘This would mean, in terms of MRG’s original thinking, that it would be working with groups, whereas most other human rights NGOs were working on the rights of individuals.’

Considerations of multiple discrimination began to influence our work in the 1990s, when gender issues were considered in all new reports, while the release of a report on Muslim women in India in 1999,was the first of our publications to deal exclusively with the rights of women from one minority group. Nevertheless, the report was not framed using an intersectional discrimination lens. Our change in approach was marked by the release of the report Twa Women, Twa Rights in the Great Lakes Region of Africa in 2003. As the second sentence of the preface states: ‘Twa women suffer from double discrimination, because of their ethnicity and their gender. These forms of discrimination can intersect to devastating effect, as in the sexual violence experienced by Twa women in the context of armed conflicts in the region.’

Since then, intersectionality has been a cornerstone of our work, informing all of our programmes and publications. Our online multimedia resource on multiple discrimination, Life at the Margins, marks our fullest exploration so far of these issues and many of its manifestations throughout the world. Furthermore, we are currently running a project on the rights of people with disabilities belonging to minority and indigenous communities, gathering data and building coalitions to work on this overlooked and often ostracized segment of the population, and have recently initiated an indigenous women’s maternal health project in Africa and Asia, with plans to address a significant lack of data in this area. As we continue to refine our approach to reaching the most vulnerable, the sentiment expressed in 1984 by our then Chair of our International Council, Professor Roland Oliver, remains true: ‘The Minority Rights Group is not there to reform the world, but to enable the muffled voice to be heard.’

Top photo: Indigenous women stand outside next to a wall in Chimborazo, Ecuador / Stephen Reich

-

By Nicole Girard

MRG became involved with Tamils in Sri Lanka with our first report in the 1970s, with regular updates thereafter. By the time Neelan Tiruchelvam joined MRG’s International Council in 1994, MRG was establishing a South Asia regional programme involving him and Radhika Coomeraswami, who were joint Directors of the International Centre for Ethnic Studies in Colombo. Both were distinguished lawyers, with Neelan Tiruchelvam being a Tamil parliamentarian. In Nepal, March 1999, he was elected Chair of MRG’s Council but was assassinated just three months later because of his strong stand for minority rights and for proposing a peaceful resolution of the Sri Lankan conflict. His life and work for peace was celebrated in a statement by the UN Secretary General. He was succeeded on the Council by Radhika Coomeraswami, who was a strong advocate of women’s rights and children’s rights; she later served as the Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations, Special Representative for Children and Armed Conflict, drawing on her personal experience of conflict and wars.

In Sri Lanka as elsewhere, women’s experience of war is different from that of men: their gendered roles and responsibilities affect the way they endure and recover from conflict. For Tamil women, the conflict and its aftermath posed specific threats of economic insecurity and sexual violence, many suffering the impact of losing male family members to unsolved disappearances. Understanding this gendered impact of war was key to MRG’s arts intervention with Tamil women in Sri Lanka, exploring concepts of hope and reconciliation, to lay the groundwork for future justice and redress.

Although the protracted conflict between the Sri Lankan military and the LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) officially ended in 2009, 20,000 persons are still considered missing. Women have been at the forefront in demanding answers regarding the whereabouts of their loved ones, endlessly putting pressure on authorities and the various commissions that have been established to address these and other post-conflict justice and reconciliation issues. And yet, women’s experience of war and the plight of their loved ones have been side-lined throughout. While hundreds of Tamil women had testified at the government-mandated Lessons Learned and Reconciliation Commission between 2010 and 2011, women’s stories were consistently interrupted and brushed over by commissioners.

In 2013 MRG, in partnership with the local Women’s Action Network (WAN), decided to take an alternative approach – using arts and poetry to give women a space to explore their experiences of war and loss. This was something that, until then, they had been unable to access, either through formal justice mechanisms or other healing initiatives. ‘I have participated in several workshops and programmes regarding peace-building and livelihood improvement,’ one programme participant recalled:

They all called and forced [us] sometime to forget the past and walk ahead. It [the MRG project] is the only programme [that] called us to memorize and to accept the past. We had the chance to share the real pain and get free a bit.

The format of the programme involved four hours allocated to art and another three for poetry exercises. Despite having little experience with either art or poetry, the women were guided first through group-oriented exercises and then moved on to individual expression. Participants were asked to draw what reconciliation means to them and then were given the chance to explain their drawings and how they felt during the process. ‘I did not use my favourite colour green in this picture,’ a 24-year-old Christian Tamil woman explained, ‘because our situation is not green now. It is so very challenging. In 2008, my brother was kidnapped by some unknown people who came in a white van. We still have hopes that my brother is alive.’

MRG’s Deputy Director Claire Thomas afterwards reflected that participants rarely had the chance to really engage in artistic expression, and its nurturance ‘had made for a more meaningful and personal exploration of reconciliation than would have been the case through a more traditional discussion format’. Thousands of Tamil women have a similar story and yet they are still not being heard by authorities. Despite this, some women at the workshop continued to have hope in the future and the potential that ‘reconciliation’ might bring. As captured in one woman’s poem:

Love is reconciliation

Relationship is reconciliation

Reconciliation is like a flower with fragrance

Pleading you, reconciliation, come to us

We have an eye on you…

We have dreams…

Don’t pass as a dream… come alive…

Reconciliation… -

By Claire Thomas

Although human rights in essence date back centuries, if not millennia, human rights as a movement really began to take off in the 1960s and 1970s. MRG’s birth was therefore at a moment when many like-minded groups were founded and momentum was building in a range of areas. However, while the majority of human rights organizations were focusing on civil and political rights issues such as torture, political prisoners and freedom of expression, from its infancy MRG focused on access to socio-economic rights – in particular, the right to an equal, quality, appropriate education for all.

Socio-economic rights were, some argue, a casualty of the Cold War, with the Western powers keen to focus on civil rights, where their track record was generally somewhat better, whereas the Eastern bloc stressed full employment and universal access to public services such as education. However, between 1971 and 1991, MRG published no less than 25 titles that called for attention to equal rights to education for minorities and indigenous peoples. These covered a very wide range of peoples and situations, from indigenous Australians, the Chinese in South East Asia, Asians in East Africa, Tamils in Sri Lanka, Tibetans, Puerto Ricans in the US, Inuit in Canada, Saami in Lapland, peoples of Zimbabwe, and Armenians, Kurds and Palestinians, as well as Bedouins of the Negev in Israel and the Occupied Territories. In addition, by 1991, MRG had published two in-depth studies on educational themes: Teaching about Prejudice and Language, Literacy and Minorities. In the 1980s MRG initiated a London’s schools education project producing a range of educational materials for the classroom which led on to the highly successful Voices project in the 1990s.

This research led, in due course, to extensive programmes on the ground that aimed to address the deep-seated inequalities faced by minority and indigenous communities in educational access. MRG specifically sought out opportunities to intervene in countries where discrimination was occurring to challenge bias and inequality in educational provision, ensuring that barriers that kept minority, indigenous and migrant children from attending or completing education were reduced or removed. This was borne out in part by the many testimonies from members of minority, indigenous and migrant communities to MRG that education represented the best opportunity for themselves and their children to escape the cycle of poverty and persecution.

Since the early 1990s, our research, campaigns and interventions have tackled everything from pointing out severe underfunding in nursery school provision in Turkana in Kenya, to documenting and addressing Batwa children’s regular experience of racist bullying and abuse from both fellow pupils and at times, teachers in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). We worked with partners in Pakistan and Indonesia, as part of community/expert-led steering groups to develop and lobby for the adoption of curricula that treated all religious groups in those countries with respect. We worked hard to develop new materials that did not include religiously discriminatory content, but also educational resources in which all communities were represented and valued. We documented and lobbied when the closure of minority-language university provision in Macedonia contributed to an outbreak of violent conflict. And we have consistently supported the efforts of Roma to access quality education across Europe, including submitting evidence and arguments in precedent-setting cases on the issue of segregated schools.

One would think that the right to education would be a relatively straightforward demand, both for communities and duty bearers. But while it is true that a campaign for equal education may be more likely to succeed than a quota of seats in parliament for a minority community, for example, the power imbalances and complex political trade-offs that impact on all states mean that achieving a fair allocation of educational budgets to minority provinces, or removing hateful content from national curricula, is much harder than it perhaps ought to be. Even on the community side, the situation is not straightforward, with some members resisting mainstream schooling as an implicit threat to their own culture and knowledge – a position that is understandable given the long history of assimilation or denigration many have experienced. MRG was involved in a UNESCO world conference on adult education in July 1997, where it facilitated the participation of minority and indigenous representatives. One indigenous activist from the Chepang community in Nepal discussed the work of their organization, Seacow, focusing on how it illustrated the need to recognize communities’ different learning systems. Essentially his argument can be summarized as: ‘Why should I send my child to your school to learn your knowledge – billions of people in the world can read and write. Our knowledge of the forest, its plants and animals, is unique and precious – if my children don’t learn it, it will be lost to humanity for ever.’ This kind of input has made MRG think very carefully about seeing education, particularly teaching in majority community knowledge and languages, as a panacea or a universal solution that we can adopt uncritically. This gives rise to a pause and acknowledgement (rarely voiced) that education can ‘do harm’ as well as good. What we need to do, then, is look not only at the extent to which marginalized communities can access public education but also the degree to which that education reflects and includes their own values, needs and aspirations.

Until today MRG has maintained its focus on education: current programmes include efforts to hold the devolved county governments in Kenya accountable for how they spend education budgets. In other countries, too, our work continues to enable minorities to access education fully and equally – most recently, with Roma mediators and local authorities in Ukraine. Where possible, we also seek to challenge boundaries and explore innovative methods to improve educational access, even in intractable and difficult contexts. One project in the troubled provincial capital of Quetta in Pakistan established ‘Bard of Peace’ clubs in schools, with the students taking up the role of ‘Bard’ and using poetry and art to generate critical thinking and reflection among pupils about religious diversity and respect for all. The students in the clubs went on to develop performances for other schools and community members on issues of social inclusion, respect for all religions and equality within Pakistan’s society.

Photo: Internally displaced children learning in Abkhazia, Georgia / Agnieszka Zielonka

-

By Rachel Warner

Voices was a series of dual-language booklets of autobiographical writing by young asylum seekers and refugees in London schools, published by MRG in the 1990s, to meet a growing need for materials that reflected the experience of young members of minority groups. The first three books, published in 1991, were by Eritrean, Somali and Kurdish school students, and the second set of four books, African Voices, published in 1995, were by students from Angola, Sudan, Uganda and Zaire (as was).

The books included drawings by the school students, photographs of their home country, maps, a fact box and a historical introduction for teachers. They were designed to be used mainly at Key Stages 3 and 4 of the National Curriculum, for English teachers encouraging autobiographical writing, for citizenship education, and as a resource for teachers of English as an Additional Language (EAL) looking for relevant materials to use with school students and adults learning English. They included detailed activity suggestions for teachers.

The books were very well received, as this review in WUS News (March 1992) shows:

The series comes at an appropriate time. It can help counter racist attacks in the tabloid press that have tried to present the majority of refugees applying for asylum as ‘bogus’. Voices shows the tragedy of disrupted lives, of suffering and of the loss of childhood. This is the truer picture – the one the press should be presenting, in which ordinary people are swept up by events over which they have no control.… This series gives refugees an opportunity to speak. It is especially poignant that it is through the voices of children that their case is made.

Tom Deveson, in the Times Educational Supplement (10 November 1995), commented: ‘This excellent series of books … should be in every school and required reading for Cabinet Ministers … and editors whose noise is in inverse ratio to their knowledge or human sympathy.’

As much as the usefulness and success of the finished books, the way of producing them was significant – involving young people and community groups at all stages of the process. Meetings were held with relevant refugee organizations at the start of the project – for example, with the Kurdish Cultural Centre, Somali Education Project and Uganda Community Association in Lambeth, as well as with the Refugee Council and Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture. It was important that the school students were asked to share their (often painful) experiences by someone they knew and trusted – usually an EAL teacher in their school. Most stories were written – either in English or the student’s first language – but some were oral accounts. All contributors checked their edited account before inclusion, and members of the community checked the books at all stages of production. All the stories were translated into the language chosen by the young contributor and presented in dual-language format. This gave the minority language(s) status in the books, and meant, for example, that Voices from Uganda included six languages in addition to English. In total, 16 different minority languages were included in the books, ranging from Tigrinya to Dinka, Acholi to Lingala, Kurdish to Arabic.

The process of producing the books was shared with many teachers – mostly in London – who attended workshops about the books and were encouraged to get their own refugee pupils to write about their experiences and produce ‘in-school’ collections of writing. It was also the inspiration for an innovative project in 2006 in Tower Hamlets, where young Somalis interviewed their own parents, leading to a publication ‘When You Lived in Somalia …’

As well as detailing some of the traumas that the young people had experienced, leading them to become asylum seekers in the first place, all the Voices books contained positive memories of the countries the young people had left. For example, a 15-year-old girl from Zaire wrote, ‘I remember us picking mangoes when the season came for the fruits to be ready. We ate most of them, but not all. There were too many.’ A 16-year-old boy from Eritrea wrote, ‘Usually I went to the cinema [in Asmara] with six or seven of my friends. We sat upstairs and made lots of noise. We were imitating the actions we saw on the film, and shouting and clapping.’

The horrors were not far away, however. A 9-year-old Somali girl in an oral account said, ‘I remember that soldiers opened fire on the kids and other people. There was a lot of screaming and crying. Pupils were falling down all around me. It was like being in a nightmare.’ A 9-year-old Angolan boy said, ‘The soldiers killed my friend Mikali. They put her by the wall and shot her. She was my friend.’

All of the books end with accounts of the difficult journeys undertaken by the young people and their families to get from their home country to Britain, and comments on settling in Britain and their new life in the country. These accounts show such resilience – for example, a 15-year-old Ugandan girl wrote, ‘I feel very happy because I was rescued from death. I could have been killed. I don’t feel like going back to my country because I am still afraid. But I would like to help in some way.’ Another (14-year-old) Ugandan girl wrote, ‘I’ve learnt to read, write and speak English better. I’ve made friends.’ And a 12-year-old Kurdish boy wrote, `I stopped crying all the time and I had a feeling things were going to work out.’

Photo: Batwa women in Uganda / MRG/Emma Eastwood

-

From the beginning, MRG has systematically focused on health services and the barriers that minorities and indigenous peoples face in accessing them. The disparities, while often overlooked, are striking: where statistics are available, health outcomes consistently show that members of marginalized communities are less healthy, die earlier and use health services less frequently than other groups. This is the case not only in contexts where services are limited and resources scarce, but also in affluent countries with well-funded health systems. In the UK, for instance, research suggests that black males have a life expectancy four years lower than their white peers.

As with education, health services are often difficult for minority and indigenous communities to access, with many barriers to equitable access in place. These include geography, with many communities situated in remote locations, far from capital cities and with little or no infrastructure in place. Language diversity and the frequent lack of comprehensible information also contribute to health inequalities. An added challenge is the widespread absence of disaggregated data on the specific situation of minority and indigenous communities – as a result, critical shortages of even basic health care can end up being concealed in national averages or overlooked altogether from official surveys.

But these challenges, which also reflect wider issues of discrimination and exclusion, can all be solved given political will. Sadly, minorities and indigenous people often have very little – if any – voice in political decision-making, including health budget allocations and priorities. At a local level, minority and indigenous communities often have no say in the design of services, which as a result can be established using a ‘one size fits all’ approach that may be culturally unacceptable: in Ethiopia, for example, painting clinics white (a colour associated with death among some communities) is one example of culturally insensitive design that was shown to have impacted on women’s willingness to access maternal health services.

Sadly, discrimination in health services can be even more direct. Minority and indigenous men and women still report first-hand experiences of explicit racism from clinic staff: from Batwa in the Great Lakes region to minority clan members in Somali IDP (internally displaced person) camps, MRG has documented numerous examples of members of marginalized communities being denied access by the very people who should be helping them. The treatment of Roma across Europe is especially disturbing. One area MRG has lobbied on was the practice of forced sterilization of Roma women in some Eastern European countries, after reports emerged on this shocking issue – a legacy of the Communist era that, while officially prohibited in the early 1990s, continued to occur more than a decade later.

Still, we have found that if we support and train activists to make advocacy claims in compelling ways, results can be achieved, against the odds. For instance, MRG was one of the first organizations to do extensive work on the practice of female genital mutilation (FGM). At the time, much of the limited coverage of this issue was coloured by stigma and misconceptions that did little to engage with the challenge of ending its devastating impacts on girls. FGM is not a minority and indigenous issue per se, as many majority community women have also been affected in different contexts. However, for communities whose culture and way of life more generally had long been dismissed or denigrated, anti-FGM campaigning could be seen as just another example of hostility towards them – even when the need in this case for urgent change was overwhelming.

Of course, we all know (now) that work to tackle FGM and similar practices needs to begin and be led by minority and indigenous women themselves, whose efforts are not dismissed as ‘yet another attack’ by outsiders. MRG’s policy of focusing on activists working directly with communities helped to achieve real impact here. This is illustrated by the legacy of Efua Dorkenoo, a highly respected British-Ghanaian campaigner who wrote one of the first reports on FGM, MRG’s Female Circumcision, Excision, and Infibulation (1980), and would later follow this with a full-length book with MRG in 1994, Cutting the Rose, when she was an MRG Council member. This book was selected by an international jury in 2002 as one of ‘Africa’s 100 best books of the 20th century’. While working with MRG, she coordinated the UK-based Women’s Action Group for Female Excision and Infibulation (WAGFEI) and travelled to a number of FGM-affected countries in Africa. Her example demonstrates how much more can be achieved in transforming health by engaging effectively, as Efua did, with those most affected.

MRG’s work on health builds on the ground-breaking research that we have undertaken over the years on behalf of communities, ranging from Palestinians in the Occupied Territories to asylum seekers in the UK. Unusually, from early on MRG also focused on mental health with reports like The Rights of Mentally Ill People (1987). This reflected our recognition that the experience of stigmatization and invisibility that many communities faced on a daily basis frequently exacted a heavy psychological toll. In more recent years, MRG has continued to develop research on health. In 2013, for instance, our flagship publication at the time, State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples, was themed around health.

One issue that MRG has consistently championed is the need for inclusive, disaggregated data for minorities, indigenous peoples and other excluded groups. Developing clear evidence to show the reality of health inequalities on the ground is often the first step to achieving change. In 2017, we co-researched an analysis of indigenous women’s and girls’ access to maternal and sexual health services, commissioned and published by UN Women, UNICEF and UNFPA. This showed that even in the era of the SDGs and their call to ‘leave no one behind’, the limited statistics available showed that indigenous women were significantly less likely to access health services. For some communities the figures were particularly stark, with indigenous women more than three times more likely than other women to have received no ante-natal check-ups. What made this situation even more worrying was the fact that out of 90 major health surveys, only 16 had collected data on indigenous women – meaning that in many, many other states no information on this was available at all.

MRG’s latest work on health has focused on training minority and indigenous community activists to understand and challenge the health budgets that are decided upon for their communities. We believe this will allow them to demand services that work for them and budget allocations that are fair, allowing health services to reach those who need them.

Photo: Somali women walking in Mandera market on the Kenyan side of the Kenyan Somali border / Kim Haughton/Alamy

-

By Claire Thomas

A recent and ongoing example of MRG’s work on health focuses on minority and indigenous women in Cambodia, Ethiopia, Kenya and Myanmar and their right to equally access sexual and reproductive health services such as contraception, pre-natal care and skilled attendance during birth. This project (funded by the UK government and run in partnership with Health Poverty Action) has three phases: first, to understand the extent to which women in minority and indigenous communities access these health services less than women nationally and why; second, to run pilot projects to tackle the barriers that are preventing women from accessing services; and, finally, to lobby for wider adoption of the successful pilot project methods so that more women benefit from these innovations. At the time of writing we are in the first phase of this project.

Some initial research focused on Mandera County in north-eastern Kenya, populated almost entirely by members of the Somali minority, has highlighted striking disparities in terms of access to essential care. Our surveys found that Somali women there were much less likely to access contraception (a shocking 1.9 per cent compared to the national rate of 58 per cent), significantly less likely to attend four ante-natal care appointments (37 per cent compared to 58 per cent nationally) and less likely to access skilled attendance at birth (39 per cent compared to 62 per cent nationally). Is it any wonder that the maternal mortality ratio in Mandera County in 2014 was 3,795 for every 100,000 live births – more than 10 times higher than the national average (362 for every 100,000 live births)?

MRG’s project has trained Somali women in Mandera to interview women within the community about why they do not or cannot access services. We believe that when Somali women themselves ask the questions, the women are more honest than they would be with an external researcher about the factors that prevent them from accessing services. Some reasons are to do with lack of provision or staffing in clinics, but some are to do with religious and cultural beliefs which women may be reluctant to discuss frankly with people from outside the community. Interviews have been carried out with 160 women and the results are being compiled. We will use this new understanding about the real barriers to accessing services, developed from within the community, to design pilot projects aiming to transform the situation.

In a linked piece of work, MRG carried out research for UNFPA on the same topic. This research analysed the data that was available globally on whether and why indigenous women access sexual and reproductive health service less than other women. We analysed 90 global surveys run by either USAID or UNICEF, which led on global health data collection. Of 90 surveys, only 8 had published data that showed whether indigenous women were able to access health services equitably. A further set of surveys had gathered that data but not published it, which we then analysed. In the end we were able to show that in the 16 cases where data existed, indigenous women were always less likely to be accessing services than the national average. This did not surprise us, but what did surprise us was the ongoing resistance to including questions about ethnicity in such surveys and publishing the findings.

MRG believes that to address a problem, you need to first collect the data and to do that you need to know which communities are benefitting from interventions or are being excluded. If you do not gather that data, or ask those questions, then you will never understand why disadvantage and discrimination are happening. And until you understand it, efforts to address it are like stabs in the dark. It is clear that, despite the fact that five years have passed since the international community committed through the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda to ensure that ‘no one is left behind’, we all have some way to go before we can claim to have delivered on that promise.

Photo: Minority woman in Somalia / Susan Shulman

-

By Neil Clarke

MRG’s work with the UN has been one of the cornerstones of its work and identity over the last 50 years. The organization’s profile as the leading international non-governmental organization (NGO) in the field of minority rights has meant that MRG has been the ‘go-to’ organization in the development of international minority rights standards and their implementation.

Pre-dating the UN, the League of Nations, founded in 1920, had the protection of minorities as a central aim of its mandate. However, following the Second World War and the founding of the UN with its key document, the UN Declaration on Human Rights, followed by a succession of other treaties, detailed reference to the rights of minorities was far more limited. This was the result of sensitivity regarding how the claims of ethnic and religious minorities might provide a casus belli for states to engage in further conflict. However, in time, it became increasingly clear that the existing norms were insufficient for the protection of minority rights and a long process began, though little progress was made on this initially with some states being adamantly opposed to recognizing the existence of minorities.

In 1989, a new order began to emerge with the new democracies in Eastern Europe, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. In the 1990s, MRG became heavily involved in the CSCE/OSCE processes, involving 51 states. It was a period of hope but old fears loomed not far away.

MRG, in partnership with the Helsinki Committees, organized major conferences in Copenhagen and Leningrad to promote a democratic and minority rights-based approach to these latent conflicts. Central to these two conferences was the engagement of civil society, including minority representatives, government officials and international scholars. The recommendations of the conferences and the mobilization of minorities directly influenced the OSCE minority rights regimes adopted in Copenhagen in June 1990 and provided a new momentum and agreed language for making progress on the text at the UN of the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities.

MRG emerged as the key civil society counterpart to government representatives at the UN during the negotiation of the text, utilizing its own expertise, led by Patrick Thornberry (later to become Chair of MRG’s International Council from 1998 to 2002) and drawing heavily on its own close discussions with minorities. Subsequently, MRG provided a platform for minority activists from around the world to argue for the adoption of the UN Declaration and the establishment of a mechanism to promote its implementation.

Eventually, in 1996, a UN Working Group on Minorities was established where MRG organized the advocacy training and facilitated the participation of representatives of minority communities. Throughout the next two decades MRG continued to play a key role in shaping international minority rights norms, not only at the UN but also within European mechanisms, leading to the adoption of the Council of Europe (CoE)’s Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities and the founding of the OSCE’s Office of the High Commissioner on National Minorities.

Throughout the last 50 years, one of the crucial areas of engagement of MRG has been in promoting the implementation of minority rights. A Director and then a Council member were independent expert members of the UN Sub-Commission on the Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities. Another Director was the President of the CoE Advisory Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM); two of our Chairpersons have been members of the UN Committee on the Elimination of all forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD); and a member of MRG’s International Council has chaired the United Nations Expert Mechanism of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (EMRIP),

A further highlight of MRG’s 50-year track record in international advocacy was its role in leading civil society lobbying for the creation in 2006 of the role of the UN Independent Expert on minority issues, subsequently renamed as the UN Special Rapporteur on minority issues, and then the establishment of the UN Forum on Minority Issues the following year, after a campaign led by MRG and the International Movement Against all Forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR). The success of the campaign for adoption was very much against the odds: indeed during the UN reform process that took place in the mid-2000s, it was feared that a space for minorities at the UN would be abolished altogether. The success of the campaign lay mainly in the coalition of 80 largely minority-led civil society organizations (CSOs) from around the world, which MRG and IMADR were able to convene, all of which engaged in lobbying and the drafting of recommendations.

However, it is not the architecture of the UN or the international normative system that is at the heart of MRG’s engagement – it is in ensuring that the presence and voices of minority activists and communities are seen and heard on the international stage and, most crucially, that these platforms can be used by activists to effect real change for their communities. Indeed, many of the CSOs which supported the campaign for the establishment of the Forum were graduates of MRG’s annual training program on UN advocacy, now running in Geneva for close to 25 years, often in cooperation with the OHCHR (Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights) Minority Fellowship Programme. These days the training specifically precedes the Forum in November each year, allowing participants to attend the event and apply their skills through active participation. Sadly, the accessibility of the Forum to minority activists is still limited, due to the failure of the UN to provide adequate funding. So MRG’s support to activists, particularly those from the global south, has been critical in ensuring the genuine presence of minorities at the UN.

There are now several other international organizations engaging with minority rights at the UN, particularly within the normative framework and development of the Forum. However, our focus on practical advocacy and strategic use of UN mechanisms, in cooperation with partners, is still unique. Indeed, while there is genuine reason for scepticism as to whether UN mechanisms are able to influence change for minority communities, our partners find different and unique values in the process. Often their presence at a UN meeting can enable a minority activist to engage in direct dialogue with a government official or create media visibility for the issues they face – opportunities that may be unavailable to them at the national level. Besides finding crucial allies and partnerships through networking opportunities they would not normally have access to, participation at a UN event can also be greatly empowering in its own right for our partners, not to mention members of MRG’s own team.

Photo: MRG staff and partners at the UN Forum for Minority Issues in Geneva, Switzerland, in November 2019

-

By Evelin Verhás

By the early 2000s, the indigenous peoples’ rights movement had successfully achieved the creation of several UN mechanisms devoted to indigenous issues, including a Working Group, a Permanent Forum and a Special Rapporteur. In contrast, the Working Group on Minorities (WGM) was the only UN mechanism exclusively dealing with minority issues. The role of the WGM was crucial in providing a platform for minorities to have a voice within the UN system, take part in policy debates and engage in dialogue with states. However, its expert-dominated agenda and limited mandate created frustration among minority representatives as they increasingly felt that their specific concerns remained unaddressed.

In an attempt to address these shortcomings, following a series of consultations with its local partner organizations, MRG launched a campaign, with support from other international NGOs, to establish a new mandate: the Special Representative of the Secretary General on Minorities (SRSG). It was envisioned that the SRSG would complement the work of the WGM and have a mandate focused on conflict prevention. By sending communications to governments and conducting country visits, the SRSG would monitor specific situations and engage with governments in a constructive manner in order to resolve issues causing tension between them and minority communities.

After gaining the support of key stakeholders, including the government of Austria, the OHCHR Indigenous Peoples and Minorities Section, as well as the WGM, the campaign concentrated on targeting member states of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) to ensure that the draft resolution calling for the creation of an SRSG put forward by Austria would pass. During the discussions at the CHR meeting, the focus on conflict prevention was deleted from the wording of resolution and it was agreed that the new mechanism would be called an Independent Expert on minority issues (IEMI).

In April 2005, the CHR resolution 2005/79 established a new special procedure, and Gay McDougall (who would go on to become Chair of MRG’s International Council from 2014 to 2020) was appointed IEMI by the High Commissioner for Human Rights in July 2005. As the first IEMI, she had the opportunity to play a crucial role in shaping the new mandate. She aimed, as she put it, ‘to give the mandate and the Declaration a global face and perspectives, and to give the issue of minority rights a twenty-first-century makeover’.

McDougall clarified the normative foundations of the mandate, articulated some definitional issues and outlined the scope of application of minority rights. She also identified thematic priorities for her work in response to the current situation of minorities. Recognizing the relationship between discrimination and poverty, she sought to increase the attention paid to minority communities in the context of poverty alleviation and development. She addressed extreme measures of exclusion, such as discriminatory denial or deprivation of citizenship, and emphasized the role of minority rights protection in preventing conflicts and promoting stability. She also worked towards mainstreaming minority issues at the UN and increasing cooperation with UN specialized agencies, treaty bodies and other human rights mechanisms.

In her six years, the IEMI sent numerous communications to governments regarding their failure to fulfil obligations to protect the rights of minorities. McDougall also carried out 12 official country visits, affording opportunities to strengthen the link between minorities and the UN. During each visit she met with minority organizations, communities and representatives, including minority women, listened to their concerns and then took these up the governments, incorporating them into her mission reports as appropriate.

In 2007, the Human Rights Council (HRC) adopted a resolution establishing the UN Forum on Minority Issues, replacing the WGM, to ‘provide a platform for promoting dialogue and cooperation on minority issues’ as well as ‘thematic contributions and expertise to the work’ of the IEMI. The IEMI was charged with guiding the work of the Forum and invited to incorporate the forum’s recommendations into her reports to the HRC.

The establishment of the Forum created the opportunity to present minority voices not only as victims describing violations but also as experts involved in formulating solutions. The IEMI also ensured that the Forum’s annual outcome documents reflected the views and recommendations of all Forum participants, including in particular those of minority communities, so the usual government-negotiated language focusing on minimum standards was avoided. Under McDougall’s guidance, the Forum became what it is today, namely an important platform for amplifying minority voices at the UN and strengthening the participation of minorities in assessing and developing international guidelines and policies aiming to improve their situation on the ground.

Photo: Ludovic Courtès, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

-

By Peter Grant

In 1970, shortly after our foundation, MRG launched our first publication: Religious Minorities in the Soviet Union. This was followed shortly after by other reports, ranging from the situation of Aboriginal Australians and that of Ainu, Burakumin and Koreans in Japan, to Asian minorities in East and Central Africa and human rights in ‘Eritrea and Southern Sudan’ (long before either region achieved independence). This snapshot offers a small glimpse of the sheer breadth and diversity of the hundreds of reports, books and briefings that have come in their wake.

Research has always played a central role in MRG’s work. In many cases, these publications helped document the challenges facing communities whose predicaments might otherwise have gone unreported. From media engagement to public advocacy, they were instrumental in achieving some of the organization’s first successes and continue to shape its activities to this day. For academics, journalists, policy-makers and, most importantly, for the communities themselves, these resources have helped to highlight the discrimination, exclusion and stigma that still define the lives of so many groups worldwide.

From the beginning, the impact of MRG’s publications was considerable. Its second ever report, The Two Irelands: The Double Minority (1971), was praised on publication for its balanced assessment of a situation too often presented in highly partisan terms. Described by Chatham House as ‘the best pages on Ireland’s contemporary political problems that have found their way into contemporary literature’, the report was credited with having an enduring impact and was still shaping discussions surrounding the Good Friday Agreement more than 25 years later. In 1997, MRG launched the book Scorpions in the Bottle: Conflicting Cultures in Northern Ireland, by John Darby (the founding Professor at the UNU International Conflict Research Institute (INCORE) in Belfast) at its international conference in London. This was accompanied by speeches from the Irish ambassador and a spokesperson of the British government’s Northern Ireland Office, both of whom commended MRG’s publications and referred to the inter-governmental discussions that were then underway.

MRG was also one of the first organizations to produce an accessible account of the Armenian genocide for an international readership. The report, The Armenians, was first published in 1976 and updated on a number of occasions over the following decade. This work was awarded the United Nations Association Media Peace Prize in 1982 for shining a light on this ‘hidden holocaust’ and the legacy of discrimination that Armenians were still experiencing in Turkey. Many of MRG’s other reports were also similarly ground-breaking in documenting the situations of communities which, at the time, had often received little or no coverage even in their own countries.

Perhaps the central achievement of our reports over the years has been to challenge the invisibility and silence that generations of minorities and indigenous peoples across the world have endured. Unseen and unheard, governments, armies, landowners and corporations have been able to exploit them in part because in many cases the communities have not even officially been recognised. When MRG published No Longer Invisible: Afro-Latin Americans Today in 1995, for instance, Afro-descendant populations in many parts of Latin America were still not included in national censuses. Increasingly, now, these communities are being acknowledged, and self-identification is growing after decades of assimilation. More recently, our 2015 online multimedia resource, Afro-Descendants: A Global Picture, drew attention to the presence of Afro-descendant communities in Asia, Europe and the Middle East, many of which are still struggling for recognition.

MRG has remained at the forefront of the discussions around minority and indigenous rights, with its World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples, first published in 1990 and then developed further in 1997 as a reference book and currently being updated in its online format, still regarded as the most authoritative resource in this area. MRG has also produced regular annual reports that have covered some of the most urgent concerns of the time, with recent volumes exploring urbanization, migration and climate change. These publications have both reflected and anticipated the changing human rights environment for minority and indigenous communities. As these challenges have evolved, so too has MRG’s approach to its research, with communities playing an increasingly central role as partners, rapporteurs and authors in describing their situations and articulating their own needs to national governments and the international community.

While looking through the back catalogue of MRG’s reports can provide many examples of hard-fought progress, it is also a salutary reminder that the struggle for justice and equality is rarely over. From Roma in Europe to Haitians in the United States, many of the groups we were working with decades ago are still experiencing the same problems today – or have new challenges that make their situation even more precarious. But it is also true that, without MRG’s reporting, the challenges facing many of these communities would not even be under discussion, and that is what will continue to drive our research in the decades to come – the need to ensure these communities are seen and heard.

Photo: Collage of report covers produced by Minority Rights Group in the 1970s-1980s

-

By Alan Phillips

The year 1989 was a watershed for minority rights in Europe. The tearing down of the Berlin Wall in Germany symbolized the rejection of the Communist system by the people of Central and Eastern Europe. Although MRG was a very small organization then, it responded speedily and effectively, drawing on its expertise, reputation and strong links with minority communities. On the one hand, there was an extraordinary atmosphere of change sweeping through Europe but also fear, particularly among western governments, that there was a strong possibility of violent inter-ethnic and inter-state conflicts mobilized by nationalist politicians.