Chagos: Britain’s Last African Colony where human rights do not exist

Right in the middle of the Indian ocean, between the Seychelles and the Maldives, lies the seemingly idyllic archipelago of the Chagos Islands. With white sands and crystal blue waters, they’re what would be seen in the west as a prime tourist destination. But behind this lies a dark history of racism that continues to this day.

These islands now find themselves in the hands of US President Donald Trump, with their uncertain future inextricably linked to the dynamics of the ’US-UK special relationship’.

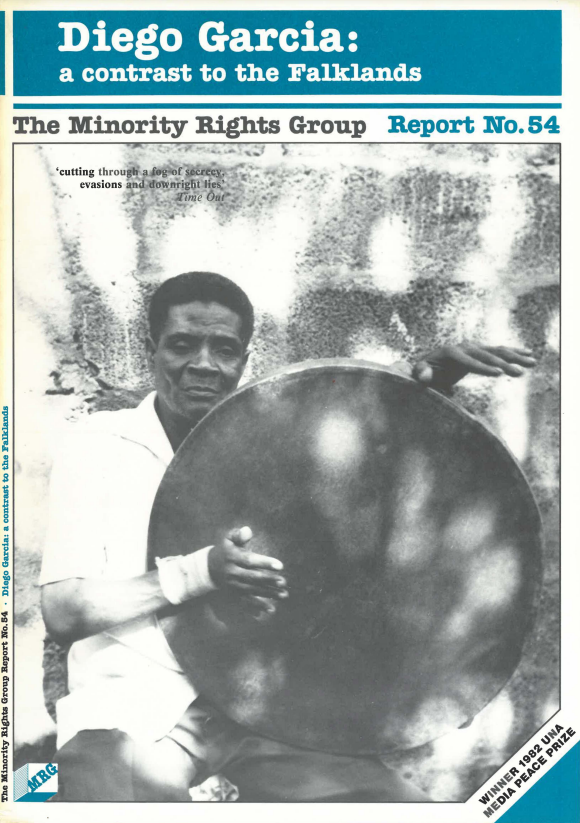

The archipelago’s first inhabitants, primarily enslaved people from Madagascar and Mozambique, were forcibly brought to the islands by French enslavers, to work on coconut plantations. Centuries later, they had unshackled themselves from slavery and become Chagossians, an indigenous people with a distinct language and culture. Nevertheless, in this time, the territory had gone from French to British rule, bringing with them South Asian labourers, and administering the territory jointly with Mauritius.

In 1965, the British convinced Mauritian nationalist politicians to give up their claim to the Chagos Islands in exchange for independence. In 1966, Chagos became the ’British Indian Ocean Territory‘ (BIOT) and was denied any claim to independence. Mauritius became independent in 1968. Retaining the archipelago as its colony, the UK proceeded to forcibly displace all Chagossians to Mauritius, the Seychelles, and eventually to the UK where they were given the right to British citizenship in 2002.

‘Our people were sacrificed for Mauritius’ independence, for this military base, for the defence purpose[s] of the west. But how about us? What do we get in return? Life in exile?’ says Frankie Bontemps, a Chagossian activist living in the UK.

With the help of the United States, Britain secretly forcibly displaced 2,000 people, and shipped around 1,200 of them to Mauritius between 1968 and 1973. The aim of this was to create a strategic military base for both the US and the UK, a plan engineered by the US who in 1958 had identified Diego Garcia, the atoll’s biggest island, as an ideal location for a base to monitor the Soviet navy. In these secret negotiations, US officials insisted the territory come under their ‘exclusive control (without local inhabitants)’ and transferred $14 million to British officials for the expulsion, which was concealed from both the US Congress and British Parliament.

Whilst Chagossians consider themselves to be the indigenous inhabitants of the island, the UK argued for decades that Chagossians were a ‘non-permanent population’ or ‘transient workers’. This refusal of Chagossian indigeneity formed the ideological basis for their expulsion.

The British would later argue that the island’s coconut plantations had dried up, and therefore the expulsion was a way for them to escape a life of poverty. Nevertheless, leaked documents written during the planning of the expulsion revealed the racist way colonial officials referred to Chagossians, calling them ‘Tarzans’ and ‘Man Fridays’, a racist expression used to describe a loyal and efficient servant. Since, both powers have tried to treat Chagos ‘as a territory where international human rights law does not apply.’

Chagossians have struggled ever since their expulsion to have their right of return acknowledged by the UK government. A small victory in 2000 was attained when a UK court declared the BIOT Immigration Ordinance of 1971 to be unlawful, which had been the basis for the forced expulsions. Nevertheless, this decision was reversed in 2004 due to US pressure, who had been using the Diego Garcia base as a strategic location for its War on Terror.

Subsequent legal cases and appeals were filed by Chagossians and by Mauritius, culminating in an International Court of Justice advisory opinion in 2019, ruling that Chagos has been unlawfully detached from Mauritius, a ruling which was ignored until November 2022.

In October 2024, the UK announced it would give up sovereignty of the Chagos Islands to Mauritius, stating that Mauritius would ‘now be free to implement a programme of resettlement on the islands of the Chagos Archipelago, other than Diego Garcia.’ This deal allows the estimated 10,000 Chagossians scattered across Mauritius, the Seychelles and the UK to return home, with the exception of Diego Garcia, which will remain a US military base for the next 99 years.

This deal has been widely opposed across the board but notably by Chagossians, who reject Mauritian sovereignty over the islands, claiming the right to self-determination – a demand recently echoed by the United Nations. It should be noted that though there are several Chagos Islands, Diego Garcia is the largest and where the majority of Chagossians originally come from.

The Chagossian Voices organisation claims that ‘Chagossians learned this outcome from the media and remain powerless and voiceless in determining our own future and the future of our homeland.’

‘We should be at the negotiating table, and they have to listen to us […] because if they want to implement any resettlement plan whatsoever Chagossians should be involved, simple like that” says Frankie Bontemps.

Despite this injustice, the fate of the Chagos Islands is still not in the hands of its rightful inhabitants, but rather in the hands of President Donald Trump who is due to announce his views on the deal in the coming weeks. Marco Rubio and Mike Waltz have also already publicly commented on the proposed plan, claiming it could jeopardise the national security interests of America due to the strategic location of the atoll, as well as China’s influence over the region.

This could amount to a major setback in the UK-Mauritius negotiations as British officials have said that ‘it is obviously now right for the new US administration [to] have a chance to consider the detail.’ A new Mauritian administration has also expressed dissatisfaction with the deal and has now submitted counter proposals to the UK.

What is certain is that there can be no justice for the Chagos Islanders without their direct involvement in the negotiation process, particularly their resettlement back to their islands. While the current deal would represent the final nail in Britain’s colonial coffin, can it really be considered justice to give the archipelago over to Mauritius? Some Chagossians have argued that there is no reason they should not return even to the uninhabited, unused eastern side of Diego Garcia, where East Point, the former administrative capital of the territory, lies abandoned. But with a new administration in the White House, what hope is there of Chagossians being given back any of the land from which they were forced?

Featured image: Chagossians protest outside the Houses of Parliament, London, United Kingdom. 7 Oct 2024. Credit: Matthew Chattle/Alamy Live News.