Somalia

-

Main languages: Somali, Arabic, Gosha

Main religions: Islam, local religions

Minorities include ‘Bantu’ (Gosha, Shabelle, Shidle, Boni), occupational caste groups (Gaboye, Tumal, Yibir, other), Oromo and Benadiri Swahili-speakers (including Rer Hamar Amarani, Bajuni), religious minorities (Ashraf, Shekal, Christians)

The Hawiye (part of the Irir clan family) is an important clan within the south-central portions of Somalia, while Darood is an important clan among all Somalis across borders. Since independence, Hawiye people have occupied important administrative positions in the bureaucracy and the top ranks of the army.

Among other groups, Somalia’s ethnic minorities include the Bantu, Benadiri (or Reer Xamar), as well as the Asharaf and Bravanese, who are based in Southern Somalia. During the civil war many members of these communities were displaced and a large number are still based in IDP settlements in Mogadishu, Puntland and Somaliland.

There are also small religious minority communities. The Ashraf and the Shekal are minorities within the majority religion of Islam. While they often experienced discrimination on the basis of their differing religious practices, Ashraf and Shekhal traditionally played important conflict-resolution roles, and were respected and protected by clans with whom they lived. However, some were badly affected by the civil conflicts of the 1990s and lost this customary protection, becoming targets for human rights abuses by clan militias and warlords. Ashraf claim descent from the Prophet Muhammad and his daughter Fatima, and believe they migrated to Somalia in the twelfth century. Ashraf from some areas are affiliated to and counted as Benadiri, while Ashraf living among Digil-Mirifle are affiliated with them as a sub-clan. Shekhal (also known as Sheikhal or Sheikash) are a similar dispersed religious community of claimed Arabian and early Islamic origin. Both Ashraf and Shekhal achieved political influence and success in education and commerce with Arab countries, yet they can still face discrimination and human rights abuses on account of their non-clan origins. The very small Christian minority, comprising first- or second-generation converts from Islam, is under extreme threat, especially now with the presence of al-Shabaab.

There are currently no reliable population statistics for Somalia due to years of chaos and war. Population figures for minorities are even more dubious and contested, with essentially no gender disaggregation. In 2002, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimated that minorities comprised one third of the Somali population. Other sources cite 20 per cent of the total population as belonging to minorities. What is clear is that minorities are splintered within society, and generally lack political and military organization compared to majority groups. The lack of comprehensive statistics extends to the disaggregation of data for different minorities – there is no clear, current breakdown in population figures for each community. It is generally assumed that the Bantu are the largest minority in Somalia: according to OCHA’s 2002 study, they comprise roughly 15 per cent of the total population, though other sources estimate that they may amount to as much as a fifth of the entire Somali population. Minorities overall are not evenly distributed throughout the country; South-Central Somalia is believed to have a higher concentration of minorities than Somaliland and Puntland. The vulnerability of IDPs – 70 to 80 per cent of which are women and children, according to the UN Development Programme (UNDP) – is especially pronounced among minority communities.

While the new Farmajo’s administration defined the draught and the consequent humanitarian crisis as priorities, many civilians faced serious and very limited access to basic services. As a matter of fact, since the agricultural sector collapsed and the forecast rain was poor, the risk of famine remained high with half of the country population still in need of humanitarian aid. Within this context, donors provided more than $1.2 billion in 2017 and, in January 2018, the UK government announced an additional £21 million in funding. According to the UN, one million people were displaced in 2017: they faced indiscriminate killings, forced evictions and sexual violence. Humanitarian agencies found several difficulties in helping vulnerable individuals since Al-Shabab banned most NGOs and UN agencies from areas under its control.

In January 2018, Africa Confidential stated that there had been no improvement in the security situation since Farmajo took office: between 2017 and 2018, hundreds of civilians were killed by the Islamist armed group Al-Shabab, especially in Mogadishu where on October 14, 2017, bombs in two lorries killed at least 358 people in the deadliest single attack in the country’s history. In addition, Al-Shabab committed several attacks against civilians and government officials: for instance, in May 2017, Al-Shabab fighters abducted civilians, stole livestock, and committed arson, causing more than 15’000 people to leave their home in Lower Shabelle. These terrorist actions generated public anger against Al-Shabab and disillusionment towards the government. In such a critical political situation, the opposition voted for an impeachment motion in the federal parliament against president Farmajo, so far without any success. Foreign interests further complicated the general political picture: several Gulf States increased their influence in Somalia by sponsoring local politicians; within the confrontation between the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saudi Arabia on the one hand and Qatar, on the other, Farmajo’s administration remained neutral. As a consequence, the Gulf States involved stopped to support payments to Somalia. In addition, in its first months of administration, Farmajo’s administration tried to improve the relations with the self-declared independent state of Somaliland without success, indeed in November, Muse Bihi Abdi of the ruling Kulmiye Party won Somaliland’s presidential elections.

Despite the fact that the government took steps to establish a national human rights commission and to revise Somalia’s penal code, there are still many controversies that should be faced. For instance, in 2017, the National Intelligence and Security Agency (NISA) and the Puntland Intelligence Service (PIS) arrested individuals without charge and tortured alleged terrorist suspects in order to get information. In 2017, despite the fact that those confessions were obtained under coercion, at least 23 individuals were executed for terrorism-related charges. Al-Shabab persisted in attacking schools, killing children using them in military operations. Against this background, despite the government tried to rehabilitate children linked to the terrorist armed group, military courts have sentenced them to heavy penalties or death. In addition, gender issues faced several hindrances: the Somalia’s penal code still defines sexual violence as an “offense against modesty and sexual honour” rather than a criminal violation against one’s integrity and dignity and it punishes same-sex relationships. In such a context, internally displaced women had to face an increasing number of gender-based violence by government soldiers and civilians.

-

For the past decade, Somalia has slowly been recovering from its status as a failed state, though significant instability persists. The country is in early stages of implementing a fledgling federal system of six proposed regions – Puntland, Somaliland, Galmudug, Jubaland, Southwest State, and Hir-Shabelle. However, political institutions established since 2012 remain weak. The resources of the Somali state also are insufficient to effectively realize the potential of it political and constitutional aspirations. Against a backdrop of persistent instability inside Somalia, minority groups such as Bantu and Banadiri continue to face vulnerability and exclusion. Other vulnerable groups include occupational minorities or clans that are associated with specific trades, such as Gaboye, Tumal and Yibrow, who work as blacksmiths, carpenters, tanners, barbers and in other trades.

In particular, the country continues to suffer from the actions of the insurgent group al-Shabab, which continues to hold large swathes of territory in the country. Civilians face serious abuses, including targeted and indiscriminate killings, forced recruitment and evictions, and sexual violence. In addition to subjecting the population in areas under its control to a range of serious human rights abuses including extrajudicial killings, the group has also launched a series of devastating and indiscriminate attacks against civilians, including a truck bomb in Mogadishu in October 2017 that killed more than 350 people. The majority of its bombing, shelling and gunfire attacks on politicians, other state officials, joint forces and civilians are in Mogadishu and the adjacent Lower Shabelle region, but also often take place in Jubaland and Puntland. UNSOM estimated that close to 1,000 civilians were killed between January and October 2018, with al-Shabaab responsible for more than half of the deaths.

However, in a context of protracted insecurity, the insurgent group is not the only source of violence, with other deaths and displacement attributable to operations against them, led by the Somali National Army, African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) troops and other foreign forces, including increasingly frequent strikes by US aircraft. A further problem is the entrenched problem of inter-clan conflict. Bantu in southern Somalia remain particularly vulnerable, and inter-clan fighting is a persistent feature of the conflict. Midway through 2018, renewed armed conflict between the Somaliland and Puntland regional governments uprooted at least 12,500 people, while across the country more than 2.6 million remain displaced.

The situation has been exacerbated by prolonged shortfall in rain across East and Horn of Africa that led to severe drought in Somalia during 2017. By the end of the year, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimated that 6.2 million people were in need of humanitarian assistance and agreed that the protection needs of minority communities and other vulnerable groups were particularly critical. The famine also swelled Somalia’s internally displaced population, estimated by the end of the year at around 2.1 million, who are especially vulnerable to sexual violence and other human rights abuses. There are fears that a similar crisis could be repeated in 2019 without adequate humanitarian funding, with top UN officials sounding the alarm that another famine could be imminent unless action was taken to avert the catastrophe. By May 2019, there were some 2.7 million people internally displaced in Somalia and 4.9 million people who were food insecure.

Many members of minorities from Somalia, without protection from dominant clans or social networks, became refugees during the past several decades of conflict. A significant Somali refugee population made its way to Kenya and has been residing there in camps for the past two decades. The situation for the 260,000 Somalia refugees in Kenya remains precarious, particularly in the wake of terrorist attacks by Al-Shabaab, with Kenyan authorities previously announcing that it would close Dabaab camp by November 2016 – a move that would have gravely endangered the residents of the camp, including a sizeable population of Bantu. However, the decision was subsequently ruled unconstitutional and the camp remains in operation, despite renewed threats by authorities to close the camp in 2019.

Dominant clans in Somalia, the Digil, Darod, Hawiye, Dir and Rahanweyn, provide protection to clan members based on a complex system of customary law and use of armed force. Those from minority groups and minority clans fall outside this system of protection. Intermarriage with minority clans is not permitted, and many other forms of interaction are frowned upon. Because of this long-standing differentiation in social status, minorities are significantly more vulnerable to human rights violations in Somalia and have few options for redress.

Access to basic services such as education, health care and shelter, as well as access to justice for violations of human rights, are significant challenges for minorities. During Somalia’s conflicts many individuals belonging to minorities were displaced internally or became refugees in neighbouring countries. Minority women in Somalia suffered disproportionate violations of human rights, as a result of double discrimination and traditional Somali patriarchy.

Somalia also includes religious minorities, constituting less than 2 per cent of the population. The majority religion in Somalia is Sunni Islam; indeed Islam is the national religion according to law and conversion from Islam as banned. Certain minority communities within the Muslim faith in Somalia, the Ashraf and the Shekal, often experience discrimination on the basis of their practice of different forms of Islam. The Christian minority in Somalia experiences severe marginalization and – in the age of al-Shabaab – extreme danger.

In a country that has not elected a government since 1969, there have been some important steps towards reestablishing representative democracy. The goal to hold one-person, one-vote elections by September 2016 has, however, been derailed by conflicts between Somalia’s dominant clans and logistical challenges derailed the process. Instead, elections began in October 2016 with 14,025 ‘electors’ divided into 51-member ‘colleges’ choosing 275 parliamentarians and 54 senators in the newly created upper house. Electors were chosen by clan chiefs to cast votes for members of parliament, who then would choose a new President. Concerns over the electoral process were manifold, including rampant corruption and intimidation

Despite these challenges, the new Parliament was sworn in in December 2016, marking a key step in Somalia’s transformation to stable democratic government. Presidential elections took place in early 2017 and were largely a contest between candidates from Somalia’s dominant clans. The country’s new President, Mohamed Abdullahi Farmajo, was inaugurated in February 2017.

Somalia’s political landscape reflects the reality of its challenges in relation to minority rights. The parliament, based in Mogadishu, is made up of equal numbers of representatives from Somalia’s four major clans and a fifth grouping of minorities which are allocated half as many seats as the majority groups – known as the 4.5 formula. In addition, a third of parliamentary seats were reserved for women candidates. Minority ethnic groups in Somalia generally are understood to include Bantu/Jareer (including Gosha, Makane, Shiidle, Reer Shabelle, Mushunguli); Bravenese, Rerhamar, Bajuni, Eeyle, Jaaji/Reer Maanyo, Barawani, Galgala, Tumaal, Yibir/Yibro, Midgan/Gaboye (Madhibaan; Muuse Dhariyo, Howleh, Hawtaar), and Oromo. The 4.5 formula is argued by some to have entrenched a historical system of minority exclusion and marginalization.

-

Environment

The Somali Republic is the eastern-most extension of the African continent, located in the Horn of Africa. It is bordered by Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean.

The southern region between the Juba and Shebelle rivers is the main area of settled agriculture. However, as only 13 per cent of the land is arable, there is intense pressure on available pasture and water.

History

At the 1884 Berlin Conference, European powers carved Somali territory into four different territories: British Somaliland, Italian Somaliland, French Somaliland (later Djibouti), and Kenya. In 1949, when Emperor Haile Selassie was reinstalled to the Ethiopian throne, Britain ceded the Ogaden region to Ethiopia. The question of reunification preoccupied successive Somali elites at the cost of addressing more concrete issues. Economic and social issues received scant attention while the cultivation of clan and sub-clan interests accentuated the demise of kinship and the rise of clannism. When British Somaliland gained independence in 1960, it immediately joined with the formerly Italian-administered Somaliland. In 1969 a military coup displaced independent Somalia’s civilian government following the assassination of President Shermaarke by a rival clan member. Mohammed Siad Barre became President.

Barre proved adept at exploiting Cold War politics for his personal gain. Initially a nominal proponent of Marxism, his regime received large-scale military and financial support from the Soviet Union. But following the 1974 military coup in Ethiopia that overthrew the US- backed Haile Selassie and brought to power the Communist Mengistu Haile Mariam, Moscow rapidly withdrew its support for Somalia’s claims on Ethiopia’s Ogaden region. When Somalia invaded the Ogaden in 1977, the Soviet Union airlifted Cuban troops to help Mengistu repel Barre’s forces. Barre deftly switched allegiance to the United States, which, especially after the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, provided lifeblood for his autocratic military regime until the Cold War’s end.

Clan rivalries

Traditional rivalries among various Somali clans, including Isaaq of the north, Ogadeni of the south and Hawiye of central Somalia, were exacerbated by Barre’s divide-and-rule policies. The failing economy and political system reawakened long suppressed discontent over the regional neglect of the north, compounded by the fact that various clan groups in the north were not treated equally. The historically strong and wealthy Isaaq had been systematically undermined in military and civil service posts and through the unequal development of resources and the location of development projects.

Barre constructed the inner core of his government from representatives of three clans belonging to the Darood clan family. By mid-1988 Somalia was embroiled in one of the most brutal civil wars in Africa, involving the government and five armed opposition groups. With dwindling US support to fight off encroaching clan militants, by 1990 Barre only controlled the capital, Mogadishu. However, in January 1991 Mogadishu fell to Hawiye clanspeople under the leadership of General Mohammed Farrah Aideed and his USC. In 1991 Barre fled to Kenya.

The downfall of Siad Barre: the effect on minorities

By 1991 Somalia was a nation without a government or central security force, where a collection of armed clan militias fought over spoils, and in a combination of political and ethnic conflict, ravaged the land and systematically killed and displaced the civilian population. During Barre’s reign, as many as 500,000 Somalis are estimated to have died and another 2 million fled their homes to become displaced persons within their own country or unwelcome refugees in Kenya, Ethiopia and Djibouti. By the time UN troops arrived in force two years after Barre’s fall, the crisis was far advanced. These two years allowed warlords to fragment the country in an attempt to consolidate shifting fiefdoms and alliances, and to deny resources to civilian communities as the source of this power. The arrival of UNOSOM, with aid and resources, provided them with a new surge of strength. Indeed, several of the warlords who came to dominate later in the decade received their initial funding through UN contracts.

Minorities were hard hit by the chaos following the fall of Siad Barre. Outside the clan system of protection, they faced expulsion from their land as well as looting by armed militias belonging to the more powerful groups. The victimization of women, particularly the displaced, was widespread. In the Shebelle region and the Hiran region north of Mogadishu, Gosha suffered displacement and starvation early on in the civil war. Scorched earth tactics were in operation against Bantu and other agricultural communities in the region between the Juba and Shebelle rivers in 1991-1992, removing their very means of survival. Communities were raided, stripped of their resources or expelled. Wells were destroyed, and seeds, stocks and livestock looted. Meanwhile, the Gaboye – accused of supporting Barre – faced brutal reprisals from Aideed’s militias. Many were murdered, others simply disappeared, their remains never discovered.

The outbreak of civil war had a disproportionate impact on Somali women, who suffered rape, displacement and limited access to essential services such as health and education in the years that followed. Another consequence of the conflict was a rise in the number of female-headed households, leaving women with the responsibility to support their families alone.

Somaliland

While Southern Somalia was tearing itself apart, the North-Western strip of the country, Somaliland, was declaring independence. This region had already had a taste of statehood in the 1960s, when it was independent for a few days in 1960 between the end of British colonial rule and its union with the former Italian colony of Somalia. This area of the country is dominated by the Isaaq clan. They had long complained that the Darood and Hawiye had dominated power and privilege in the country at the expense of Isaaq since independence, and that southern Somalia, being both more developed and denser in population, had tended to dominate the northern region. In an attempt to crush the Isaaq Somali National Movement in the late 80s Barre’s military unleashed terrible force against civilians. Tens of thousands of civilians were killed and at one point around 90 per cent of Hargeisa – the main town in the area – was destroyed. Some 400,000 people fled into eastern Ethiopia.

Since 1991, Somaliland has formed a breakaway region of Somalia, dominated by the Isaaq clan, though its independent status has yet to be recognized by the United Nations. Nevertheless, this northern area was relatively calm while the rest of the country remained immersed in chaotic inter-clan warfare. In October 2008, however, a series of bombings across Somaliland and Puntland killed nearly 30 people and led to fears about deteriorating security here too.

Puntland

Another area which has autonomy is Puntland. This area in central Somalia is dominated by the Majerteen clan, and under Siad Barre’s regime, the area had suffered harsh treatment because of the presence of the rebel SSDF movement. In May-June 1979, over 2,000 people died of thirst and the clan lost 50,000 head of cattle and 100,000 goats. In 1998 under Majerteen leadership, the region declared autonomy. Its stated goal was the establishment of a federated Somalia rather than the independence sought by neighbouring Somaliland. As has been the case with Somaliland, Puntland’s support from Ethiopia has further inflamed tensions with southerners.

Attempts to restore central governance and the rise of al-Shabaab

Up to 2004, there had been 14 attempts to restore a central government to Somalia. The 2004 effort resulted in lengthy peace negotiations in neighbouring Kenya, which were held under the supervision of several Horn of Africa states. This finally resulted in a new agreement in August 2004 to create a new Transitional Federal Government (TFG). In October 2004, the Transitional Federation Assembly (TFA) elected Puntland’s President, Abdullahi Yusuf, a Darood, to serve as president of the TFG. The following month the President named Ali Mohammed Gedi, a Hawiye – but one lacking clan backing – as prime minister. The new transitional assembly – also elected in Kenya – had 30-odd seats reserved for minorities. It was a small but largely symbolic step forward as from the outset there were doubts about the TFG’s ability to take control of the country. The TFG inherited the clan-based power sharing system, the ‘4.5 formula’ 2004. It allows half a seat to representatives from minority clans for every four seats held by members of majority clans. Although the number of minorities in Somalia remains difficult to count, it is likely to be much higher than the 4.5 formula suggests, and even within the given ratio, members of majority clans continue to disproportionally dominate.

Islamic courts with backing from Hawiye businessmen seeking a more secure environment began to subdue the warlords in the capital. Amid the uncertainty of everyday Somali life in the south, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) gained popular support and were able to establish order through Sharia law, although women and non-Muslims found themselves living under stricter conditions.

In June and July 2006, the ICU defeated a coalition of militia leaders, taking control of the capital and other parts of the south. Mogadishu and its surroundings were calmer and safer than at any time since 1991. The ICU accused the TFG of receiving direct Ethiopian military assistance, and called for holy war on Addis Ababa. This in turn fuelled Ethiopian concern about secessionist sentiment in its Somali Region. The United States also grew concerned about the ICU, accusing it of maintaining links to Al Qaeda. In November 2006 the Ethiopian government admitted to military engagement in Somalia, and with the backing of United States air support, routed the ICU from Mogadishu and southern Somalia in the following month. But Ethiopian forces, backed up by a small contingent of African Union peacekeepers from Uganda and later Burundi, struggled to impose their control in the face of a growing counter-attack by factions including remnants of the ICU operating under the name al-Shabaab (‘youth’).

Al-Shabaab started out as the youth wing of ICU and developed into a hardline military force that opposes any UN or AF led peace process, which the more moderate ICU would support in the framework of a power-sharing agreement between the Islamists and the government. There was a renewal of bitter clan fighting, as largely Hawiye fighters have clashed with Ethiopian forces and their Darood allies. Heavy-handed tactics by Ethiopian troops increased popular opposition to the invasion. US air strikes on alleged terrorist targets in 2007 and 2008 also killed civilians and may have contributed to greater support for al-Shabaab militants. In October 2007, the struggling government entered into a power-sharing deal with a more moderate Islamist faction and called for the withdrawal of Ethiopian forces. Ethiopia, whose troops had been subject to fiercer counter-attacks than anticipated, agreed. As the last of its forces withdrew in January 2009, the government remained only in control of the town of Baidoa and some neighbourhoods of Mogadishu. For its part, al-Shabaab announced that it would now turn its full attention to targeting AU peacekeepers in its effort to establish an Islamic state.

In its 15th attempt to set up a government since 1991, the parliament elected a new moderate Islamist president from the Hawiye clan in early 2009. Sheikh Sharif Ahmed is reported to have headed the Sharia courts movement that brought some stability to Mogadishu and most of south Somalia in 2006, before Ethiopian military ousted them. Ahmed chose a Darood, Omar Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke as prime minister in a power- sharing government intended to end civil conflict, resettle the displaced and facilitate international aid. Prime Minister Sharmarke resigned from the TFG in September 2010 and was replaced by Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed. In August 2010, the TFG drafted a new Constitution and launched a consultation process.

Fighting between al-Shabaab and TFG forces, the African Union Mission for Somalia (AMISOM) continued throughout 2009. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that in May 2009, more than 200 civilians were killed, at least 800 wounded and some 121,000 displaced by the first week of June 2009. It is reported that over the weekend of 5-7 June alone, some 30,000 people fled the city, and several thousand people experienced a second round of displacement. According to reports by Amnesty International, members of minority groups remain displaced for comparatively longer periods. Violence and continued military atrocities are not limited to the capital but spread to several major towns in South and Central Somalia. On 17 May 2009, al-Shabaab forces took control of Jowhar town (90km north of Mogadishu) and raided humanitarian supplies, assets and equipment. This act has serious country-wide humanitarian implications as Jowhar is the main hub for the provision of humanitarian services and supplies to the whole of South-Central Somalia.

Continuous fighting in Mogadishu marked 2010 as the worst year for Somalian violence in over a decade. UN figures reported an average of more than 20 weapon related casualties per day over the year. Al-Shabaab and Hizbul Islam launched a new offensive against the TFG in May, which intensified during the months of Ramadan (August-September). Al-Shabaab also claimed responsibility for the 11 July bombing in Kampala, Uganda, which they said was a response to Uganda contributing troops to AMISON in Somalia. Al-Shabaab made significant territorial gains in 2011 gaining control of most of South-Central Somalia from the Kenyan border to regions bordering Puntland, whilst the TFG controlled only a few blocks of Mogadishu around the Presidential Villa. In 2010 al-Shabaab enforced a version of Shari’a law which is severely in breach of international legal standards. This includes a number of ‘morality laws’ such as the systematic closure of cinemas, and bans on khat, smoking and music. Huge restrictions were also placed upon women, who were prohibited from leaving the house alone and forced to wear the abaya, a garment supplied by al-Shabaab which covers the whole body.

Continued challenges despite post-conflict stabilization

With the TFG’s mandate set to expire, in August 2012 the National Constituent Assembly, consisting of clan elders, local leaders, youth, and women, overwhelmingly passed a new Constitution by a margin of 621 to 13, with 11 members abstaining.29 Subsequently, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud became President – the first to be elected from within Somalia since the start of the civil war more than two decades before30 – and a 275-member parliament was selected by clan elders. These milestones were deemed a significant step in the country’s transition toward democracy, and ushered in a new era of hope whereby Somalia could finally move from conflict and instability to peace and redevelopment.

Somalia continues to struggle with humanitarian crises, attacks from a resurgent al-Shabaab and weak governance, with central governance still fragmented by competing clan rivalries and vested interests. The situation has been aggravated by environmental pressures such as drought, bringing with them famine and displacement.

Governance

In the absence of central governance, and with the exception of brief rival administration by Islamists and an attempt to form an inter-clan government, a fractured Somalia has fallen under the shifting control of competing clan elites. Somalis belonging to clans constitute 85 per cent of the country’s population. Within a caste-like hierarchy, Somalis are divided into three to five major clan families; the number and definitions of these are contested. Most conventional descriptions of Somali society identify 4 or 5 major clan groups: Dir, Isaaq, Hawiye and Darood, who make up higher Samaal castes, and Digil-Mirifle/Rahanweyn (sometimes mentioned as two distinct clan groups), belonging to the low-caste Saab. Some consider the Isaaq part of the Dir clan. Each clan comprises numerous subfamilies and lineages. Sixty per cent of the population is nomadic and concentrated primarily in the north.

While clan refers to the social organization, clannism is the politicization of the clan structure by elites, for personal gain. The clan is an important social organization in the Somali social structure. It affects politics, economics and social status. For minorities, the clan structure poses special difficulties; the Bantu, Gaboye, Bendari and others lie outside the system. They have no political power, and during upsurges of the conflict, have been especially exposed. Without militia protection, they are vulnerable to attack and to having their properties seized. Thus, in a country where all residents face some degree of threat, minorities are at special risk.

Clan relationship is regulated by the Somali customary law, xeer. This is particularly important in view of the absence of well-functioning modern state structures in Somalia and a well functioning judiciary system. In most of the southern Somali regions is the customary law that is utilised to regulate social relations. The clans use deeply ingrained customary law – or xeer – to govern their communities. Besides determining one’s origin, social standing and economic status, clannism permeates nearly every aspect of decision making and power sharing in the country. In the best case, the clan may provide a social security welfare system for its members – but at its worst it leads to conflict, bloodshed and xenophobia. Xeer also governs the relationship between minority and majority communities, but does not always provide the same level of protection to minorities as majority clans. In fact, minority communities previously relied on majority clans for protection through sheegat or sheegasho, whereby minority groups would become closely associated with a majority clan through provision of some service or compensation in exchange for protection. Such protective relationships mostly came to an end with the onset of the civil war, when majority clans targeted members of particular minority clans due to their limited numbers and lack of military organization.

Despite efforts to reform and strengthen formal governance in Somalia, the new government is currently able to provide only limited protection for minorities and offers limited opportunities for participation for women, with no clear recognition of their rights in Somalia in its 2012 Constitution, nor an explicit minimum quota for female representation in parliament. Nor have authorities appeared to exploit the post-conflict ‘window of opportunity’ to build more inclusive institutions for minorities and women – for example, by revising the controversial ‘4.5’ system.

This controversial power-sharing formula, providing equal political representation to the four major clans, while the country’s remaining minorities receive an additional half-share as a collective, has attracted continued criticism since its inception in 2004. On the one hand, commentators saw it as a good temporary stepping stone toward a power-sharing mechanism that could eventually lead to a one-person, one-vote political system. However, while the system was designed to encourage power-sharing and prevent a particular group monopolizing decision making, it has been criticized for deepening social divisions and failing to reflect the true composition of the Somali population. Out of a total of 275 seats in parliament, the four major clans are each guaranteed 61 seats, while minority clans have only 31 seats. Some commentators have suggested that the 4.5 ratio should be increased to 5 to provide minority clans with better representation. Furthermore, the 4.5 arrangement fails to reflect the diversity of Somalia’s minorities, reducing all of the various minority clans to a 0.5 subgroup and ignoring the range of societal customs that characterize each one. As the 0.5 subgroup is not based on the actual net population, it does not provide equal representation: on the contrary, it places limits on the space for political participation among minority groups and facilitates the domination of government and other political structures by majority clans. The argument that minorities should be given greater representation appears to have gained some acceptance: for example, it has been observed that cabinet selections under Hassan Sheikh’s presidency worked using the 5, rather than 4.5, distribution structure. Despite this headway, however, little progress has been made to adequately incorporate minority clans (and by extension minority women) into the political sphere.

-

As is apparent from the other pages of this Directory entry, minority communities face marginalization and exclusion in all facets of life. National and Local NGOs are, sadly, not necessarily an exception. There are historically documented examples of majority clan individuals and organizations presenting themselves as minorities where a quota for minority inclusion has been established or benefits are being targeted to minorities to try to redress inequality.

For this reason, MRG maintains a list of organizations that have undergone a careful validation process to verify any claim that they were founded by minorities, are led by minorities or involve significant numbers of minority personnel in their workforce. Organizations which do not meet these criteria do, of course, in many cases work hard to genuinely include minorities in their programmes, but given the overall context, they do not have the same relationships of trust with minority communities that a minority-staffed organization can develop and they cannot be said to represent minorities. The list is not exhaustive: for example, it is possible that a minority-founded or led organization has not yet come to our attention. Nonetheless, we encourage anyone intervening in Somalia who wishes to consult or involve minority communities to consult the list and reach out to these organizations. The list also states which organizations are women-led, and which geographical areas each organization covers.

The organizations vary widely in capacity, some are very large, established organizations who are eligible to receive SHF funding or who work with large international IGOs or NGOs. Others are established, running several schools or clinics but survive primarily on contributions from the diaspora. Others are very small organizations with very limited staffing and no or almost no funding.

It is difficult for these organizations to compete on a level playing field with established NGOs in Somalia who are majority led, have strong connections with people in powerful places and have been able to establish a much larger track record of running projects.

Whilst national and local NGOs, in general, may have resources in place to support wider efforts, (e.g. vehicles, staff who visit beneficiary locations regularly, paid monitoring staff, paid finance staff), minority organizations who have been starved of opportunities or funding for decades may not have this and if their contact and trust with minority communities can make a contribution to the inclusive programme, their costs may need to be covered in a way that would not be the case for regular partners.

The verification process that each organization on the list has gone through is complex and nuanced but involves the following elements:

Somalia NGOs

- Virtual or face-to-face conversations with senior staff/board members of organizations to assess their knowledge of and ability to cite known contacts with/location of relevant minority communities.

- Verification through contract tracing of any claimed minority clan background of senior staff, founder(s) or board. (This may not be needed where the individual is a visible or linguistic minority).

- Verification that the organizations’ past work has included genuine efforts to consult, involve and benefit minorities.

- Visibility of minorities/discrimination in the organization’s public-facing materials.

- As a supplement to the above, and never relied on solely, contact with trusted sources who know the organization’s work well and can verify their personnel, track record and commitment.

This list will be updated periodically so please check back regularly.

Afar-waab-dhoobooy Young Professional Association (AWYPO)

Focus area: Lower Shabelle, Middle Shabelle | Expertise: WASH, Nutrition, Gender

Contact: Qassim Mohamed Muse, Chair, 615537529, [email protected]Asal Community Development Organization (ACDO)

Focus area: Jowhar, Mahadaay, Beletweyne, Banadir | Expertise: WASH, Nutrition, Protection, Gender, Health

Contact: Hassan Muhudin Mohamed, Coordinator, 615509190, [email protected]Bridges Of Hope (BOH)

Focus area: Banadir | Expertise: Food security, Health, Wash, CCCM

Contact: Abukar Abdi Bule, Executive Director, 615531325, [email protected]Burhakaba Town Section Committee (BTSC)

Focus area: Bur Hakaba | Expertise: WASH, Education

Contact: Mahbub Dahir Hussein, Project Manager, 615740758, [email protected]Community Empowerment for Relief Developm (CERD)

Focus area: Jowhar, Mahaday | Expertise: Food security, Health, Wash

Contact: Abdikadir Yaquub Sidow, Chair person, 617836164, [email protected]Daami Youth Development Organization (DYDO)

Focus area: Somaliland (Hargeisa, Borame, Burco) | Expertise: CCCM, Protection, Food security, Governance

Contact: Mohamud Mohamed, Executive Director, 654103314, [email protected]Gurmad Walal Organization (GWO)

Focus area: Balad, Jowhar, Mahaday | Expertise: GBV, Health, Nutrition, Protection, CCCM

Contact: Eng- Aweys Mohamed, Program Coordinator, 615968663, [email protected]Hawa Sheikh Oyaye Relief Organization (HSHORO)

Focus area: Jowhar, Mahadaay, Beletweyne, Banadir | Expertise: Protection, WASH, Nutrition

Contact: Daud Sidow Sheikh Ali, 615524123, [email protected]Humanity Inclusion Sustainable Advocacy (HISA) – Significant female leadership

Focus area: Banadir, Lower Shabelle | Expertise: GBV, Health, Nutrition, Protection, CCCM

Contact: Shukri Abass Ibrahim, Program Coordinator, 616103083, [email protected]International Development African Associate (IDAA)

Focus area: Lower Shabelle, Bay, Bakool | Expertise: Food security, Health, Wash, CCCM

Contact: Suleiman Madhimba, Executive Director, 615551309, [email protected]International Relief Foundation (IRF)

Focus area: Banadir, Lower Shabelle | Expertise: Education, Nutrition, Protection

Contact: Mohamed Hussein Enow, Deputy Chair, 615252276, [email protected]Juba Valley Development Center (JVDC)

Focus area: Banadir, Lower Shabelle | Expertise: women empowerment, Protection

Contact: Mohamed Aweys Honero, Executive Director, 615527997, [email protected]Khalif Hudow Human rights organization (KAHRA)

Focus area: Lower Shabelle, Banadir, Bay | Expertise: GBV, Health, Nutrition, Protection, CCCM

Contact: Yussuf Digana, Program Director, 612573084, [email protected]Livelihood Relief and Development Organization (LRDO)

Focus area: Lower Shabelle, Banadir, Bay | Expertise: GBV, Health, Nutrition, Protection, CCCM

Contact: Yussuf Abdi Lari, Executive Director, 618395386, [email protected]Maani Vaccational Training Centre (MVTC)

Focus area: Lower Shabelle (Marka, Qoryooley) | Expertise: CCCM, Protection, Food security, Governance

Contact: Abukar Abdikadir Mohamed, CEO, 615900199, [email protected]Marginalized Communities Advocacy Network (MCAN)

Focus area: Banadir, SWS, Jubaland | Expertise: GBV, Health, Nutrition, Protection, CCCM

Contact: Ibrahim Hassan Mohamed, Executive Director, 613656423, [email protected]Marginalized Communities Advocates (MCA)

Focus area: Afgoye, Janale, Banadir | Expertise: GBV, Health, and Nutrition

Contact: Dr, Muse Hussein Abdi, Chair person, 618232680, [email protected]Minorities and Vulnerable Groups (MVG)

Focus area: Baidoa, Hiraan, Banadir, Lower Shabelle | Expertise: WASH, Protection, Youth, Nutrition, Health

Contact: Mohamed Abdulkadir, Manager, 615293766, [email protected]Minority Women Associated & Child care (MWAC)

Focus area: Banadir, Lower Shabelle | Expertise: GBV, Health

Contact: Abdirisaq Ibrahim, Chair person, 619560931, [email protected]Puntland Minority Women Development Org (PMWDO) – Significant female leadership

Focus area: Bossaso, Qardho, Garowe | Expertise: Women empowerment, Protection

Contact: Burhan Shil, Program Manager, 907795961, pmwdo2000@gmailcomSave Minority Women and Children (SMWC) – Significant female leadership

Focus area: Baidoa, Hiraan, Banadir, Lower Shabelle | Expertise: Health, Food security, Protection

Contact: Munira Abdiladhif; Shukri Abas, Co-Chairs, 615273746; 61, [email protected]Shabelle Youth Association (SHABIA)

Focus area: Lowershabelle, Banadir | Expertise: Nutrition, protection, education

Contact: Mohamed Hagi Sufi Abdulle, Chair, 615907954, [email protected]Somali Intellectuals for Minority Advocacy and Empowerment (SIMAE)

Focus area: Baidoa, Hiraan, Banadir, Lower Shabelle | Expertise: Protection, WASH, Nutrition

Contact: Liban Mursal (Chairpeerson), Amina Mohamed Abdi (Coordinator), 619600799; 617868247, [email protected]Somali Minority Development Organization (SOMDO)

Focus area: Jamame, Kismayo | Expertise: CCCM, Protection, Food security, Governance

Contact: Abdikadir Ali Abdi, Executive Director, 618213018, [email protected]Sun Relief Development Organisation (SURDO)

Focus area: Buale, Bardhere | Expertise: Protection

Contact: Abdi Yussuf Abdi, Executive Director, 700795486, [email protected]Sustainable Livelihood Relief Organization (SLRO)

Focus area: Gedo, Middle Juba | Expertise: CCCM, Protection, Food security

Contact: Abdirashid Mohamed, Program Coordinator, 717238397, [email protected]USKESOCBA

Focus area: Middle Shabelle, Banadir | Expertise: women empowerment, Protection

Contact: Hassan Amir Hussien, Program Director, 616501465, [email protected]Voice of Somaliland Minority Women (VOSOMWO) – Significant female leadership

Focus area: Somaliland (Hargaisa, Borame, Burco) | Expertise: Health, Food security, Gender

Contact: Abdullahi Osman, Chair person, 637158615, [email protected]We Elitrate (WE)

Focus area: Lower Shabelle (Marka, Barawe), Banadir | Expertise: CCCM, Protection, Food security

Contact: Khalid Macow, Program Manager, 616982869, [email protected]Women Dialogue Inclusion (WDI)

Focus area: Banadir, Lower Shabelle, Gedo | Expertise: GBV, Health, Nutrition, Protection, CCCM

Contact: Ayaan Abdi Mohamed, Program Coordinator, 615840111, [email protected]Women Initiative Development Network (WIDEN)

Focus area: Marka, Barawe | Expertise: Education, protection, gender

Contact: Mana Abdalla Shariff, Chairperson, 615839231, [email protected]

Updated June 2019

Related content

Latest

View all-

12 October 2023

MRG calls for linguistic inclusivity and minority rights in Somalia

This statement was delivered on 10 October 2023 by Shukri Abbas during the Interactive Dialogue with the Independent Expert on Somalia at…

-

31 March 2023

Magical Moments: Claire Thomas reporting from Somalia

I had the privilege of visiting Somalia last week, for our programme to improve polio vaccination coverage through minority inclusion. I…

-

25 October 2022

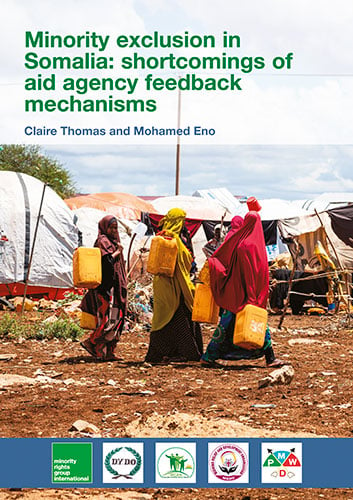

Minority exclusion in Somalia: shortcomings of aid agency feedback mechanisms

In 2021, MRG research revealed that minority clan members in Somalia were less likely to be aware of, to trust and to use the feedback…

Reports and briefings

View all-

13 November 2023

Language barriers in polio vaccine campaigns in Somalia

In this collaborative report, CLEAR GLOBAL, HISA, JVDC, MCAN and Minority Rights Group International explore the comprehension of polio…

-

25 October 2022

Minority exclusion in Somalia: shortcomings of aid agency feedback mechanisms

Most aid agencies operating in Somalia have established complaints and feedback mechanisms (CFMs) in an effort to address longstanding…

-

30 January 2015

Looma Ooyaan – No one cries for them: the situation facing Somalia’s minority women

After decades of violence and instability, tentative progress is being made in Somalia to strengthen the country’s governance and…

Technical guidance

-

- East Africa

- Marginalization

- Technical guidance

Partner publications

-

1 June 2021

A Survey Report on how the marginalized communities in IDP sites in Mogadishu and Kismayo perceive their exclusion

This Survey was conducted by the Marginalized Communities Advocates – Network (MCA-N) with support from UNHCR targeting a population…

Don’t miss out

- Updates to this country profile

- New publications and resources

Receive updates about this country or territory

-

Our strategy

We work with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples to secure their rights and promote understanding between communities.

-

-