Suriname

-

Main languages: Dutch, Caribbean Hindustani, Javanese, Sranan Tongo (English-based Creole), Chinese, English, French, Spanish, indigenous languages

Main religions: Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, indigenous and African-derived spiritualities

Main minority and indigenous groups: Hindustani (East Indian) 27.4%, Maroon 21.7%, Creole 15.7%, Javanese 13.7%, Mixed 13.4%, Indigenous Peoples 3.8%, Chinese 1.5% (percentages from 2012 Census)

Overall population: 626,505 (based on an elaboration of the latest United Nations data in January 2024, pending the next census)

The religious profile of Suriname is Protestant 23.6% (includes Evangelical 11.2%, Moravian 11.2%, Reformed .7%, Lutheran .5%), Hindu 22.3%, Roman Catholic 21.6%, Muslim 13.8%, other Christian 3.2%, Winti (Afro-Surinamese syncretic religion) 1.8%, Jehovah’s Witnesses 1.2%, other 1.7%, none 7.5%, and unspecified 3.2% (2012 Census).

Suriname is a pluralistic society comprising mainly the descendants of Indian and Javanese (Indonesian) contract workers, the descendants of escaped African slaves known as Maroons, and Creoles (persons of mixed African and European heritage). Suriname has a small indigenous population descended from the first inhabitants of the region. East Indians (persons of South Asian descent) now form the largest group, constituting nearly one-third of the total population, followed by Maroons who represent approximately one-fifth. There was a sizeable increase in the number of respondents self-identifying as Maroon in 2012. In the 2004 Census, 14.7 per cent identified as such, meaning that Creoles were then the second-largest community.

In Suriname, more than 20 languages are spoken, but only Dutch is the official language. Sranan Tongo, a Creole language, is used as the main mode of communication (the lingua franca) between the different ethnic groups.

The country is often divided into three distinct settlement areas: urban, rural and ‘Interior’, which is also referred to as the ‘hinterland’. ‘Urban’ refers to the capital city of Paramaribo and its surroundings, where the government is seated, and the majority of the population is based. ‘Rural’ refers to the northern coastal zone (the districts of Nickerie, Coronie, Saramacca and Commewijne), in which, previously, most of the plantations were situated and where agriculture traditionally formed the main economic activity. The ‘Interior’ is generally reserved for the sparsely populated and forest covered hinterland that forms part of the Amazon basin and which stretches towards the southern border with Brazil. Administratively, this area comprises three districts: Sipaliwini, Brokopondo and Marowijne. The majority of the population in these districts belong to indigenous and Maroon communities, which are historically, economically and culturally distinct from the rural and urban populations.

Suriname is party to various universal and regional human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. The country voted for the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007. However, the country’s legislative structure, based on colonial laws, still does not recognize indigenous peoples. Suriname is one of the few countries in South America that has not ratified the International Labour Organization’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention No. 169.

-

Environment

Suriname is located in northeastern South America. It is bounded on the north by the Atlantic Ocean and shares borders to the east with French Guiana, to the west with the Republic of Guyana and to the south with Brazil. The climate is characterized as tropical wet and hot. It is generally controlled by the biannual passage of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ): once during the period December to February (known as the short wet season), and a second time during the months of May – mid August (long wet season). The periods in between are the short dry season (February to the end of April) and the long dry season (middle of August to the beginning of December).

Suriname is South America’s smallest sovereign state. The country has an area of 163,265 sq km (63,037 sq mi), and its southern part along the border with Brazil consists of dense tropical rainforest and sparsely inhabited savanna. Tropical rainforest predominantly covers the country. Suriname is considered a negative carbon emitting country, as its rainforests absorb more emissions than the country emits. It is a high forest cover and low deforestation (also known as HFLD) country that accounts for 0.01 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The economy of Suriname is heavily reliant on the services and extractive industries. The agriculture and forestry sectors are considered to be the country’s commercial pillars. Agriculture contributes an estimated 12 per cent to Suriname’s GDP; it also accounts for 10 per cent of total export earnings, employing approximately 8 per cent of the total labour force. Rice and bananas are the main crops. Maroon communities are custodians of heritage rice varieties, hidden and cultivated centuries ago by escaped slaves. These rice strains are again proving crucial to Maroon farmers as they seek to use variants that can cope with the changing climate. In the interior, indigenous communities rely on the forest as their source of food, fuel, medicines and agriculture, using shifting cultivation.

The country has abundant natural resources, with mining accounting for nearly half of public sector revenue and about 90 per cent of total exports. Gold alone represents more than three quarters of exports; other important mining products are alumina, bauxite and oil. The two largest multinational mining companies operating in the country are IAMGOLD based in Canada and the US company Newmont Corporation.

Small-scale informal gold mining is the predominant form of gold extraction, using basic prospecting and extraction techniques. The activities are carried out by a workforce with limited if any professional training and far from the control of government bodies. It is often illegal. Surinamese companies such as Sarafina NV, Bishumbar and Grassalco Nalso facilitate small-scale mining operations. Industrial gold mining also has a strong presence in the country, and many of the larger concessions are granted to international companies. Mercury contamination as a result of gold production is a significant concern.

With more than 15.2 million hectares of forest cover, approximately 93 per cent of Surinamese land is covered by forest, which makes the country one of the most forested countries in the world. The country is classified as a high forest / low deforestation (HFLD) country. Annual rates of deforestation nevertheless increased from an average of 0.2 per cent during the period 2000-2009 to an average of 0.5 per cent per year in the period 2009-2015.

Suriname’s forests are part of the Amazon biome. The country’s forests host significant levels of biodiversity. According to its profile with the Convention on Biodiversity, Suriname possesses seven types of ecosystems: marine ecosystems (Atlantic Ocean, mud banks, sandbanks, mudflats), coastal ecosystems (mangrove forests, mangrove swamps), brackish water ecosystems (brackish water pans and lagoons), freshwater ecosystems (freshwater swamps, open freshwater systems such as the Upper Rivers and rapids in the Interior), savannah ecosystems (white and brown sand savannahs, rock savannahs), marsh ecosystems, inselbergs and tropical rainforest. The country has 22 protected areas, 20 are national and two are international. The largest one is the Central Suriname Nature Reserve which comprises 1.6 million hectares of primary tropical forest and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 2023, Suriname’s government announced plans to become the first country to sell carbon credits under a system set up by the 2015 UN Paris Agreement to help curb climate change. Meanwhile, plans also emerged in 2023 that hundreds of thousands of hectares of rainforest may be cleared to make way for agriculture; critics questioned how the two initiatives could be compatible with each other. Indigenous leaders were particularly vocal, as the clearance of vast swathes of forest on indigenous lands would take place without their consent and would significantly harm indigenous livelihoods.

History

The smallest independent country in South America, Suriname, formerly Dutch Guiana, was colonized and held by the Netherlands until 1975. This determined not only the imposition of Dutch as the official language but also the strong economic and diplomatic ties with the Netherlands, which continue to this day.

Suriname was originally inhabited by many distinct indigenous peoples such as Taíno (Arawak), Kali’nago (Carib), Warrau Wayana and Akurio. After a hundred years of Spanish domination and at the beginning of the 17th century, the first Dutch arrived to explore the territory, which came under the control of the Dutch West India Company, founded in 1621. Dutch control of the territory experienced setbacks, such as attacks and occupation by the French and the British. A small British settlement was established in 1650; it was then that the first African slaves were brought to the region. It was only in 1667 that the new Dutch hegemony was consolidated, with the end of the Anglo-Dutch war and the signing of the Treaty of Breda, in which the Dutch territory in North America, then called New Amsterdam, today New York, was exchanged for the English territory in the north of South America, which was renamed Dutch Guiana.

From the beginning, the Dutch colonizers exploited African slave labour to cultivate various crops, including coffee, sugar, cotton and coconut. In addition to farming, during this period the region served as a supply depot for travelers passing through the Caribbean on their way to South America. The Dutch West India Company controlled the territory until 1794, when it officially became a Dutch colony. Despite some progress in the legislative arena, Suriname only gained its own parliament in 1866.

Dutch settler control of the Guiana coast caused the territory’s indigenous peoples to retreat into the interior to avoid extinction. This period was also marked by an immense influx of African slaves. Dutch traders were among the first to establish slave forts and castles on the coasts of West Africa and enslaved and imported hundreds of thousands of Africans to Suriname, including many of Akan and Ashanti origin. It is estimated that between 1667 and 1863, the territory received around 325,000 enslaved Africans, many of whom died because of the brutality with which they were treated on the trans-Atlantic voyages and on the plantations. Plantation conditions were brutal, and life spans were short. Others, in turn, escaped and formed independent communities in the rainforest. After 1690, there were constant records of escapes by slaves from the plantations to form their own settlements.

This resistance led to the emergence of a unique Maroon culture with its own spiritual practices, drawing upon the African civilizations from which the slaves and their ancestors had been abducted. One event that deserves to be highlighted was the insurrection between 1762 and 1763, involving attacks by Maroons and in which a large number of slaves fled into the forest. After half a century of guerrilla warfare against colonial troops, Maroon communities signed treaties with the Dutch government in the 1760s, enabling them to live a virtually independent existence until well into the 20th century. Maroons contributed significantly to the eventual abolition of slavery.

Suriname is the location of one of the earliest Jewish synagogues in the Americas. The Jodensavanne settlement was established in the 1680’s by Sephardic Jews on indigenous territory. Today, the archaeological site includes the ruins of a synagogue, cemeteries and a military post; the remains of the settlement were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2023. The Jewish community lived alongside free and enslaved Africans, as well as indigenous people. As a result, Suriname is home to a rich and complex Jewish-Creole heritage.

Post-abolition

The Dutch ended chattel slavery in 1863 but demanded obligatory but paid plantation labour by former slaves for another five years. Mostly Chinese indentured labourers were then brought from the Netherlands East Indies. Between 1873 and 1916 in an agreement with the British, many East Indian labourers were also imported from north Indian states such as Bihar and Eastern Uttar Pradesh. After 1916, labourers especially from Java were again brought from the Netherlands East Indies (today Indonesia).

In terms of political life, ethnic, cultural and language differences made it difficult for a national consciousness to emerge. This diversity manifested itself in the programmatic lines of the emerging political parties, which represented the interests of ethnic groups, in turn mirroring the interests of various economic sectors. The Party for National Unity and Solidarity (KTPI) represented the interests of the Indonesian community. Afro-descendants formed the National Party Combination, an alliance of four centre-left parties, which demanded independence in the aftermath of World War II. Indo-Surinamese created the Progressive Reform Party (VHP). There are also parties that represent categories, such as the Progressive Workers’ and Farmers’ Union (PALU), for labourers and farmers. The National Democratic Party (NDP) was formed in 1987; it has its origins in the February Twenty-Five Movement (VFB), linked to the military.

An administrative council was set up in 1948, and, in 1949, the Surinamese gained universal electoral suffrage. About a year later, they were granted the right to elect their own government but without control over foreign policy and defense issues. Partial independence was achieved in 1954: Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles became constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. That year, elections were held for parliament. The Electoral Act was based on racially demarcated constituencies. Economic, cultural and linguistic factors already divided the country’s ethnic groups; this legislation encouraged ethnic divisions to extend into political organization.

Johan Adolf Pengel, the Afro-Surinamese leader of the National Federation of Trade Unions of Suriname and President of the National Party of Suriname (NPS), governed the country from 1958 to 1963 and was re-elected with the title of Minister President of Suriname.

In October 1973, the independence movement – a Creole-East Indian party coalition – won the legislative elections, and Henck Arron, liberal leader of the NPS, became Prime Minister of the local government. Independence was finally proclaimed on 25 November 1975, following an agreement between Arron, representing Creoles, and Jagernath Lachmon, whose party, the VHP, represented the Indo-Surinamese community. A number of people (approximately 40,000) chose to retain Dutch citizenship and emigrated to the Netherlands.

Re-elected in 1977, Arron was the victim of a military coup on 25 February 1980, after three years in power. Désiré Bouterse, the leader of the coup that became known as the Sergeants’ Revolution, dissolved parliament, abolished the Constitution, declared a state of emergency and took nationalist positions, promoting total post-independence autonomy for the Netherlands. From the outset, his administration was accused by the opposition of using repressive methods. To form the government, the National Military Council (NMR), a group led by Bouterse, called in left-wing leaders. That same year, the country was divided into ten administrative districts: Brokopondo, Commewijne, Coronie, Marowijne, Nickerie, Para, Paramaribo, Saramacca, Sipaliwini and Wanica.

This government remained in power for about a year, until the NMR, accusing military leaders of corruption and spurious relations with the Netherlands and the United States, launched a new coup on 4 February 1981. The new government, led by Bouterse, established relations with Cuba, which earned it internal opposition from the main parties, and external opposition from the Netherlands and the United States. The atmosphere of popular revolt intensified in the early 1980s with the strong depreciation of bauxite on the international market, culminating in 1982 with a movement of traders and trade unionists challenging the Bouterse government. These demonstrations were vigorously suppressed. The crackdown resulted in the killing of fifteen leading opponents of the regime, including a former minister, a professor and a union leader, on 8 December of the same year. The claim was that they were preparing a countercoup. These murders are now an important part of national history and are known as the December Murders.

In January 1983, Bouterse formed a new government with civilians and the military, appointing Errol Alibux as Prime Minister, a nationalist associated with PALU. There was a shift in foreign policy following the invasion of Grenada by the United States, and in the same year the government asked Cuba to withdraw its ambassador. Between late 1983 and early 1984, a wave of strikes paralyzed bauxite mining – which at the time accounted for 80 per cent of exports. Bouterse again dismissed the Prime Minister and the cabinet, appointing union leaders to the cabinet instead and annulling the tax measures that had been applied. This was a period also focused on reducing dependence on the Netherlands, both politically and economically, by diversifying Suriname’s foreign relations through membership of international organizations and agreements with other countries.

As a result of increased repression in the early 1980s, opposition movements became more radicalized. In 1986, the Suriname Liberation Army (also known as the Jungle Commando) was formed, led by Ronnie Brunswijk, who was antagonistic to the authoritarian government and demanded that the Constitution be reinstated. Brunswijk also sought to gain greater recognition of the rights and needs of the Maroon community. The Jungle Commando conducted guerrilla activities against military posts on Suriname’s eastern frontier. There were civilian casualties as a result of these attacks, and some 4,500 refugees, mainly Maroons, fled at that time to French Guiana.

In November 1986, a Surinamese military unit launched an operation against the N’djuka Maroon village of Moiwana, claiming that it was Brunswijk’s base. At least 40 residents were systematically killed in what became known as the Moiwana massacre. In 2005, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ordered Suriname to pay compensation to the survivors, establish a development fund for the community and prosecute those who were responsible for the atrocities. The decision remains only partially implemented.

The return to institutional rule began in April 1987, albeit still under military control, when the National Assembly unanimously approved a draft Constitution. The democratic process resumed with the victory of the New Front for Democracy and Development (NF) coalition in the January 1988 elections, which brought Ramsewak Shankar to the presidency. On 21 July 1989, Shankar signed an agreement with the still active guerrillas, recognizing their right to remain armed inside the jungle. Bouterse and the NDP, on the other hand, led the opposition to the agreement, claiming that it would legitimize an autonomous military force within the country. In 1990, Bouterse led a new military coup, which ousted Shankar and dissolved the National Assembly. Johan Kraag of the NPS, an ally of the President, was provisionally appointed to the presidency in 1991. France and Suriname agreed to provide for the repatriation of an estimated 10,000 Surinamese refugees from French Guiana. After alleged attempts at forcible repatriation, some 6,000 refugees voluntarily returned.

After the turbulent period between the 1980s and 1990s, at the beginning of the 21st century Suriname began to enjoy relative economic and political stability, although the country still faced serious challenges. Agreement was reached with the guerrilla movement in May 1992. Guerrillas were included in the amnesty previously extended to the military, and the government promised that the interior of the country would become a priority for social and economic development.

In December 2023, Bouterse and four other ex-military officers had their convictions upheld by Suriname’s highest court for their roles in the December Murders of 1982. This was Bouterse’s last chance to appeal against the case which was brought against him in 2007. The three-judge panel sentenced him to 20 years’ imprisonment. At the time of this update, Bouterse has disappeared, and Interpol has issued a ‘red notice’ for his arrest.

Governance

Suriname is a constitutional democracy that holds generally free and fair elections, according to observers from the Caribbean Community and the OAS. The president is chief of state and head of government and is elected to five-year terms by a two-thirds majority of the National Assembly. If no such majority can be reached, a United People’s Assembly—consisting of national, regional and local-level lawmakers—chooses the president by a simple majority. President Chandrikapersad Santokhi and Vice President Ronnie Brunswijk were chosen in July 2020, in accordance with the procedure established in law.

-

Since the 1960s, development and resource extraction incursions into Suriname’s interior have become commonplace. These increased rapidly in the 1990s, in a movement known as the second gold rush. Gold extractors generally use hydraulic equipment, namely high-pressure hoses to soften the gold-bearing layer, before using mercury amalgamation to separate out the gold. The resulting mercury pollution has severe consequences for the environment and the human settlements that depend upon it.

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Suriname’s gold mining with mercury amalgamation is the main and almost exclusive source of anthropogenic releases of mercury into the country’s environment. In 2018, the country ratified the Minamata Convention, an international agreement addressing mercury pollution, especially in gold mining. However, Suriname’s mercury emissions from anthropogenic sources, nearly 90 metric tonnes per year, is among the highest in the world relative to the country’s size, according to its Minamata initial assessment (which used 2018 figures and was published in 2020). Gold mining contributes 97 per cent of that pollution. These were the most recent figures that were available when this entry was updated.

The large amounts of mercury that are used by the mining sector presumably enters the country illegally. According to a report published by Dialogue Earth in 2020, although the mercury trade is regulated, not a single legal import had been recorded in fifteen years. Given that gold production is so underpinned by illicit imports of mercury, it is not surprising that mining is also connected to other illegal activities, such as tax evasion and human trafficking.

Mercury pollution is rampant, and a significant part of Suriname’s population is at risk of elevated levels of mercury exposure due to upstream mining activity. Suriname’s rivers flow downstream into the Atlantic Ocean along the coastline where most of the country’s inhabitants live. The largest districts of Paramaribo, Wanica and Commewijne together had close to 400,000 inhabitants and approximately 74.5 per cent of the country’s total population in 2012. The Suriname, Commewijne and Saramacca Rivers flow into these districts and are all heavily affected by high intensity gold mining further upstream. Many indigenous communities are particularly at risk of dangerous levels of mercury exposure due to their reliance on fishing. According to Dialogue Earth, nearly half of the wild-caught predatory fish register elevated amounts of mercury.

An estimated 20,000 to 35,000 people work in Suriname’s mining industry, although the most accurate figure (including informal miners) may be twice that number. Small-scale gold production is particularly associated with Maroon communities, which have been pursuing this artisanal form of mining for generations. However, most of the workers in this sector are migrants from Brazil, referred to as garimpeiros, who introduced the hydraulic method to the region in the early 1990s and now account for around three-quarters of the gold mining population in the country. The remaining gold miners are mostly N’djuka, Paamaka and Matawai Maroons, and city dwellers (non-Maroons) who often perform specialized tasks, such as mechanics or excavator operators. Chinese immigrant workers have recently begun to participate in Suriname’s small-scale gold mining.

Small-scale and industrial gold mining in Suriname continues to take place within the boundaries of traditional Maroon territories. The majority of Maroons live in the central-eastern part of the country, which is also where the mineral-rich Greenstone Belt and gold deposits are located. In some Maroon villages such as the Paamaka, Aukan and Matawai communities, inhabitants have become economically dependent on gold mining. Small-scale gold mining is therefore the predominant economic activity among Maroons and affects their communities in a variety of harmful ways, as reflected in the increased number of cases of malaria, sexually transmitted diseases (STD’s) and mercury poisoning which are registered amongst residents.

Suriname is highly vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Among the factors that intensify its vulnerability are the degradation of important ecosystems and the fact that 87 per cent of the population and most of the country’s economic activity are located within the low-lying coastal area, along the 386 km long coastal plain (around 67 per cent in Paramaribo). This makes the country very exposed to extreme weather events, including floods, droughts and high winds. Thirty per cent of Suriname is within a few meters above sea level, which increases its vulnerability. The country is prone to periodic flooding due to heavy rainfall, especially when combined with spring tides. Flooding affects most of the population, including an estimated 90 per cent of human activities, and is exacerbated by poor drainage in the relatively highly populated urban areas along the coast, such as the capital city of Paramaribo. Additionally, Suriname faces extensive coastal erosion and higher temperatures during dry seasons.

As a result of climate change and La Niña weather patterns, the country experienced particularly heavy rainfall in 2022 which caused severe flooding in the districts of Brokopondo, Sipaliwini, Marowijne, Para, Saramacca, Coronie and Nickerie. In Brokopondo and Marowijne districts, 15,000 people were affected and 2,000 were displaced by floods across the two districts; some areas were under 4 to 6 meters of water. These intense downpours deposit significant amounts of water in shorter time frames, resulting in instances of waterlogging as the soil eventually becomes unable to absorb all the water. In the case of the 2022 floods, the state-owned oil company Staatsolie opened the sluices on the Afobaka dam to ease pressure on the Brokopondo reservoir. Fields cultivated by Maroon farmers were left submerged for months. Effects included an increase in the mosquito population, heightening the risk of malaria, as well as damage to water treatment plants, curbing wastewater treatment.

Despite the clear threat posed by the climate crisis, the country’s extensive forest coverage may face renewed threats. Currently, approximately 93 per cent of Suriname is primary forest, which means that it is one of the few countries in the world that is carbon-negative, emitting less CO2 than it emits. In 2023, plans emerged that the government is considering setting aside hundreds of thousands of hectares of land for agricultural purposes. This would mean that vast areas of rainforest would be cut down. The Association of Indigenous Village Heads in Suriname (VIDS) denounced the plans, stating that the livelihoods of Suriname’s indigenous peoples were threatened. Others questioned how this could be consistent with the government’s intention to earn billions of US dollars from carbon storage and absorption.

-

Environmental

Indigenous

Maroon

- Maroon Community Support Initiative

- Association of Saamaka Authorities (Saamaka- oto, also Vereniging van Saamakaanse Gezagsdragers)

- Maroon Women’s Network

Wayana

- The Mulokot Foundation

Updated June 2024

Related content

Reports and briefings

-

1 July 1987

The Amerindians of South America

For over 20,000 years a wealth of many cultures flourished in South America, both in the high Andean mountains and the lowland jungles and…

-

1 April 1984

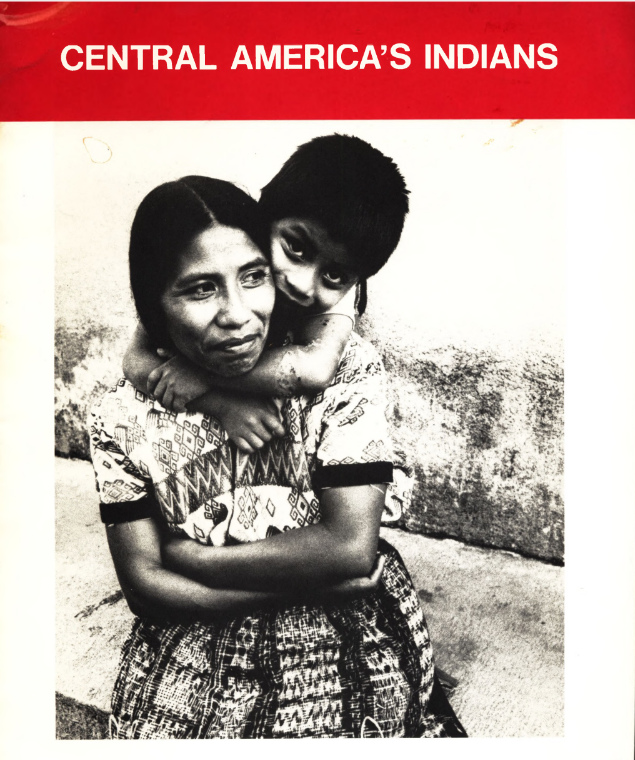

Central America’s Indians

In Latin America today we find one of the largest remnants of colonialism in the world. The concept “Indian” itself is, of course, a…

-

Our strategy

We work with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples to secure their rights and promote understanding between communities.

-

-