Female indigenous activism in Guatemala: inspiration and challenges for women and girls as agents of change

Part two of two

Roslynn Beighton is a former communications intern at MRG and now works for Fern, an organization which campaigns for the protection of the world’s forests and forest peoples.

Introduction

Mayan women represent significant actors in resistance movements and social development organizations calling for basic human rights in Guatemala. During a research trip earlier in the year, I was fortunate enough to meet and stay with some truly inspiring female activists who are working exceptionally hard to fight for their basic human rights – as women and as members of various Mayan ethnic groups.

In just under four weeks I navigated my way across eight departments of Guatemala, via local ‘chicken buses’ winding their way over the country’s hair-raising roads. I was interested to find out what motivates Mayan women to create and occupy spaces for activism, as well as explore the obstacles they face in mobilising in such spaces. With the help of MRG and Peace Brigades International (PBI), I interviewed several Mayan women working in rights-based grassroots organizations .

Barriers to female indigenous activism: ethnic discrimination

Every activist I interviewed recounted how they had been discriminated against for their ethnicity for as long as they could remember. Belen, a young woman working in a community radio station told of times when she had been denied employment over ladina women, despite having more qualifications and experience for positions. She was upset that she was seen, firstly as lower than men because of her gender and secondly as lower than other women because of her traje which represents her ethnicity as Quiché.

“If I’m wearing a trouser and a blouse, nobody sees me in a funny way but if I’m wearing my custom dress people avoid me because they don’t want to get close to me. It’s due to a misconception that indigenous people smell bad, that we don’t shower and we live in an uncivilized way as we live in the countryside, in the mountains. People mistreat us. We can actually get used to it but it hurts sometimes… if you are sitting in a place they tell you to move and leave the place to a ladino.” Belen

The most unjust aspects I found in response to the social movements these women are a part of is the direct and indirect resistance they face from the state, as a result of structural inequalities that have plagued this country since the Spanish conquest. Smear campaigns stigmatizing and discrediting activists for environmental and social issues falsely accuse them of extremism and they are increasingly at risk of violent attacks, defamation and death. PBI documents 223 assaults, 14 killings and 7 attempted murders registered between January and November 2016 against human rights defenders. In 2016, Guatemala was named one of the most dangerous countries on Earth for activists working to defend and protect natural resources.

The government’s ‘war on indigenous peoples’ prevents indigenous females from participating in spaces for the advancement of their rights because they fear for their safety and security. I spoke at length with Maggie’s intelligent younger sister Diana, who wished for better conditions for other Mayan women as well as access to the water resources of Atitlán which have always been a source of life for Kaqchikel villagers. However, she refused to join her sister’s movement because she agreed with her mother Felipa: it was too dangerous to fight ‘the bigs’.

Barriers to female indigenous activism: violence against women

A common theme I found in my interactions with the activists I engaged with is Guatemala’s extreme sexist attitudes, which are embedded within a culture of machista thinking. Asociacion Ixqik, a women’s rights organization in the far north of the country who invited me to their offices in San Benito, near the idyllic island of Flores, claimed domestic violence is the biggest issue faced by indigenous women and the primary obstacle to their participation in social activism. GBV directly blocks the development of spaces for activism by impacting upon the physical and mental well-being of women. Furthermore, it has severe indirect consequences generally unassociated with physical harm.

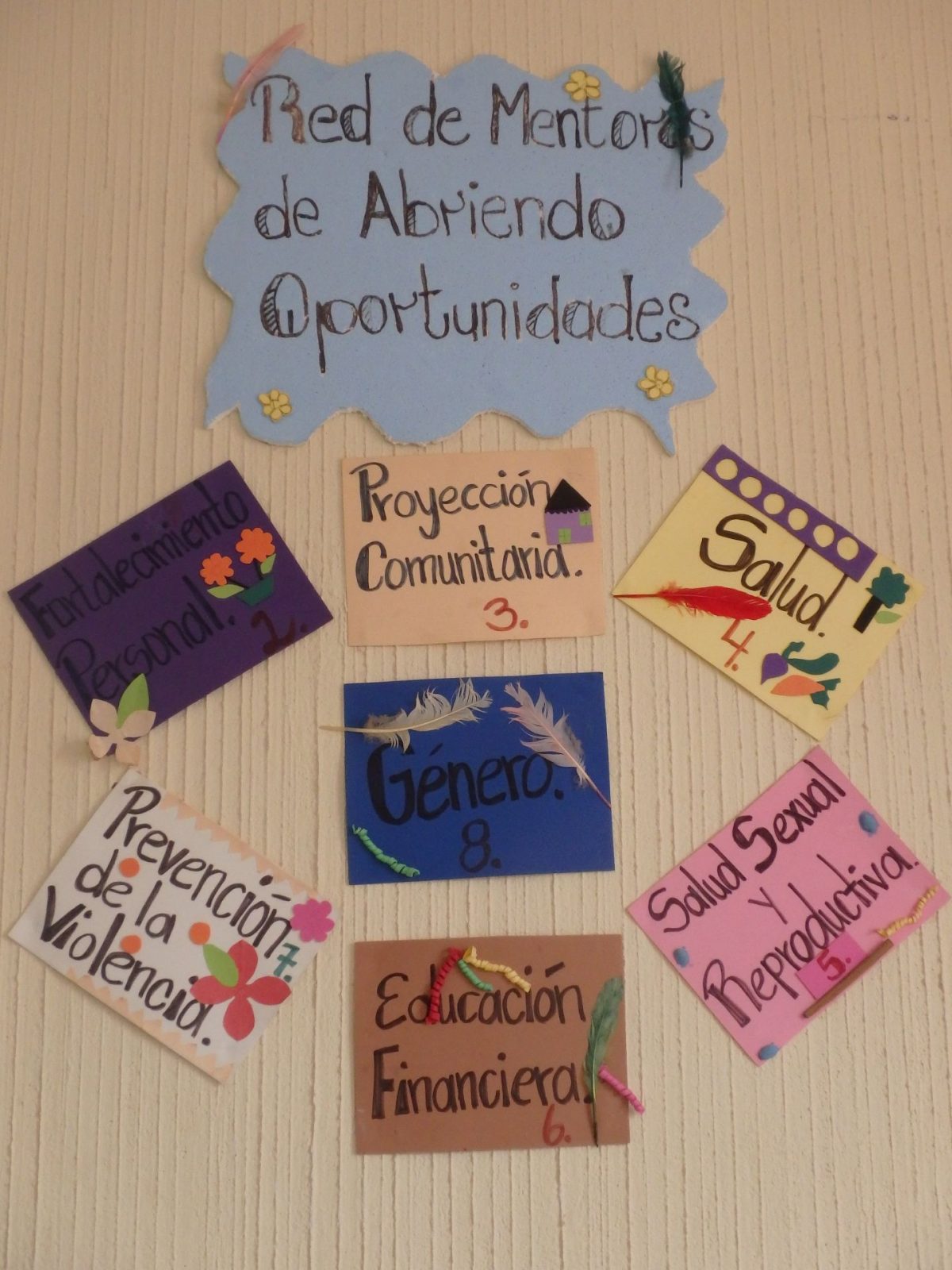

Indigenous women face reduced opportunities for advancement in critical causes, which relate to the expectations placed on them from birth. The young community mentors of Red Abriendo Oportunidades told me they had grown up being told that women were supposed to have babies and keep a clean house. Most women do not have the time to dedicate to activist work as they are focusing on the survival of their children and families. They are often not allowed out in the evenings, which is the main time of day when men organize around rights-based movements and it is considered taboo for them to be physically present for dialogues. Critical attitudes (from the family to the national level) can lead to feelings of fear and inferiority that actively demotivate females from being involved in movements. A grave concern is that the denial of women’s capabilities in leadership can solidify barriers to spaces for activism through the development of an inferiority complex in women and girls which can stop many women from speaking out about their abuses and taking their work seriously.

Moreover, the unavailability of resources restricts pathways for participation in spaces which promise empowerment of women and indigenous peoples. Mayan women are in the weakest socio-economic position in Guatemalan society. It is especially difficult for them to seek justice and defend their rights without the means to become aware of the factors determining their situation in the first place and even more so when considering the restrictive roles women occupy in their communities.

State structures which are both racist and sexist at times directly block indigenous women’s ability to access basic services, such as healthcare and education, let alone afford them the spaces they need to organize and resist their oppression.

Role models

Despite the challenges I was told about and witnessed first-hand, it is clear many spaces for female indigenous activism are created and occupied ‘internally’ at the localised level by women who should be seen as agents of change, rather than simply victims of a viciously unjust system. My conclusion from my trip is based on the impact of role models who are strengthening spaces for individuals and groups of women to participate in improving conditions for women and all members of their indigenous communities.

Some interviewees saw true role models as women who possessed a raw energy to protect the living world, and were dedicated to an indigenous way of life, or at least a life that was not corrupted by capitalism:

“Who represents us? Those fighting to defend the territory; few women are fighting but they are leading and doing real things. They are in their territory, in their remote villages defending their lands against mining and electric companies, against those life models that affect us. Those are the true indigenous, and for me, those are the ones who represent the town and inspire me.” Maggie

“If you ask anyone who Joan of Arc is they are going to tell you they don’t know. But when you hear what Doña Juana, for example, is doing in the community and how she is defending and standing against the mines, that inspires you and it inspires the community.” Norma

My interviewees’ impassioned speeches show that the role models who motivate indigenous women to participate in activist spaces are not necessarily self-proclaimed feminists or famous global leaders. They are fundamentally protectors of their loved ones, defenders of basic human rights and preservers of Mayan cultures. Overall, the analysis of role models exposes how central ethnic identity is to these women and other activists like them. They are driven by a force which is paramount to their sense of purpose as members of Mayan communities which are threatened. They must choose to either channel their repression into a positive movement or succumb to a life of discrimination. They choose the former.

I feel incredibly humbled to have had the opportunity to meet such strong and inspiring female indigenous activists. I am appreciative for their hospitality, generosity and friendship, without which my study would not have been possible. Thank-you very much to: Maggie Garcia, Felipa Cos, Norma Mejía, Belen Pak, Carmen Alicia Torres Hernandez, Elvira Chuktiu, the women of RED Abriendo Oportunidades and the women of Asociacion Mujeres de Petén Ixqik.