Japan’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples: A History of Denial

The chapters

Japanese society is at a crossroads. With a population that is not only ageing but also in decline, there is an urgent need to attract migrant workers into the country.

- 01

Introduction

Japanese society is at a crossroads. With a population that is not only ageing but also in decline – some estimates suggest it could reduce as much as 30 per cent over the next 50 years – there is an urgent need to attract migrant…

2 min read

- 02

Buraku: Living with the legacy of caste

For many centuries, when Japan was structured along feudal lines, the lowest category of all were known as eta or hinin – derogatory terms for outcaste groups typically associated with stigmatized work, such as butchers and leather…

1 min read

- 03

Sumiyoshi: The history of a Buraku neighbourhood in Osaka

This difficult history of Japan’s Buraku population is illustrated by the case of Sumiyoshi, an area of southern Osaka home to a community dating back hundreds of years: there appears to be documentary evidence of Buraku as far back as 1284,…

2 min read

- 04

Foreigners in their own country: The plight of ethnic Koreans

It is estimated that there are up to 1 million ethnic Koreans living in Japan today, almost half of whomIt is estimated that there are up to 1 million ethnic Koreans living in Japan today, almost half of whom do not have Japanese…

1 min read

- 05

The challenges of Korean education in Japan

While education is often seen as the best chance of a more inclusive future for Japan’s minorities, the issue of minority schools is currently one of the most contested in the country – with Korean schools in particular on the frontline…

1 min read

- 06

From assimilation to recognition: Japan’s indigenous Ainu

The challenges of assimilation and invisibility in Japan are starkly illustrated by the recent history of the Ainu community. Indigenous to the northern islands of Hokkaido, for centuries they maintained a lifestyle of hunting, fishing…

3 min read

- 07

Still unrecognized: Ryūkyūans

Ryukyuans, also known as Okinawans, have inhabited Okinawa through a long and often difficult history that has included colonial rule and occupation. Though previously claimed by the Japanese shogunate in the early seventeenth century, it also…

1 min read

- 08

For Japan’s migrant population, life on the sidelines takes a heavy toll

With falling fertility rates and an ageing population, Japan’s demographic challenges are especially acute. Around 28 per cent of the national population are now 65 or older, a proportion that is set to rise further in the coming years…

5 min read

-

Japanese society is at a crossroads. With a population that is not only ageing but also in decline – some estimates suggest it could reduce as much as 30 per cent over the next 50 years – there is an urgent need to attract migrant workers into the country. Nevertheless, the launch of a new policy to allow entry to hundreds of thousands of foreign workers to fill the current labour gap has proved divisive.

The heated debate around immigration and its impact on national identity reflect a deeper unease about diversity in general – a situation that is tied inextricably to Japan’s recent past. This includes, among other human rights abuses, the repression and assimilation of indigenous peoples such as Ainu and Ryukyuans, as well as the emergence of minorities such as Koreans and other groups through occupation and labour migration.

A parade in Osaka in 2018, celebrating diversity and calling for recognition of minorities. The continued refusal among Japanese nationalists to acknowledge this traumatic history shapes the experiences of these groups to this day. They have all contended, in different forms, with marginalization, exclusion and invisibility: indeed, some are still unrecognized by the Japanese government as distinct communities. From hate speech and stigmatization to official discrimination and dispossession of land, minorities and indigenous peoples in Japan still face many challenges.

This online resource presents an overview of their struggle to secure their place in Japanese society, and the need for a more welcoming and inclusive approach to immigration. With the forthcoming Olympics in Tokyo celebrating ‘Unity in Diversity’, it is time for the country to put these principles in practice – beginning with rights and recognition for its minority, indigenous and immigrant communities.

The author would like to thank all the activists and academics who gave their time to be interviewed for this piece. He is especially grateful to Megumi Komori of the International Movement Against all forms of Discrimination and Racism (IMADR) for all the assistance she generously provided.

-

For many centuries, when Japan was structured along feudal lines, the lowest category of all were known as eta or hinin – derogatory terms for outcaste groups typically associated with stigmatized work, such as butchers and leather workers. Living in isolated communities on the margins of society, they were eventually classified together as Burakumin (literally ‘hamlet people’) and suffered a range of dehumanizing policies in their everyday lives.

With the abolition of the feudal system in 1871, Buraku were granted legal equality for the first time. In practice, however, they were still widely ostracized. Over time, as Japan urbanized, many of these formerly rural settlements became neighbourhoods in towns and cities across the country, particularly Osaka and Kyoto, still segregated from surrounding areas and with little in the way of public services such as clean water or sanitation. Despite efforts to mobilize a countrywide Buraku movement with the foundation of the National Levellers’ Association in 1922, later renamed the Buraku Liberation League after World War Two, their exclusion persisted – a situation that nevertheless paved the way for a period of extraordinary activism by the Buraku community.

A period of activism

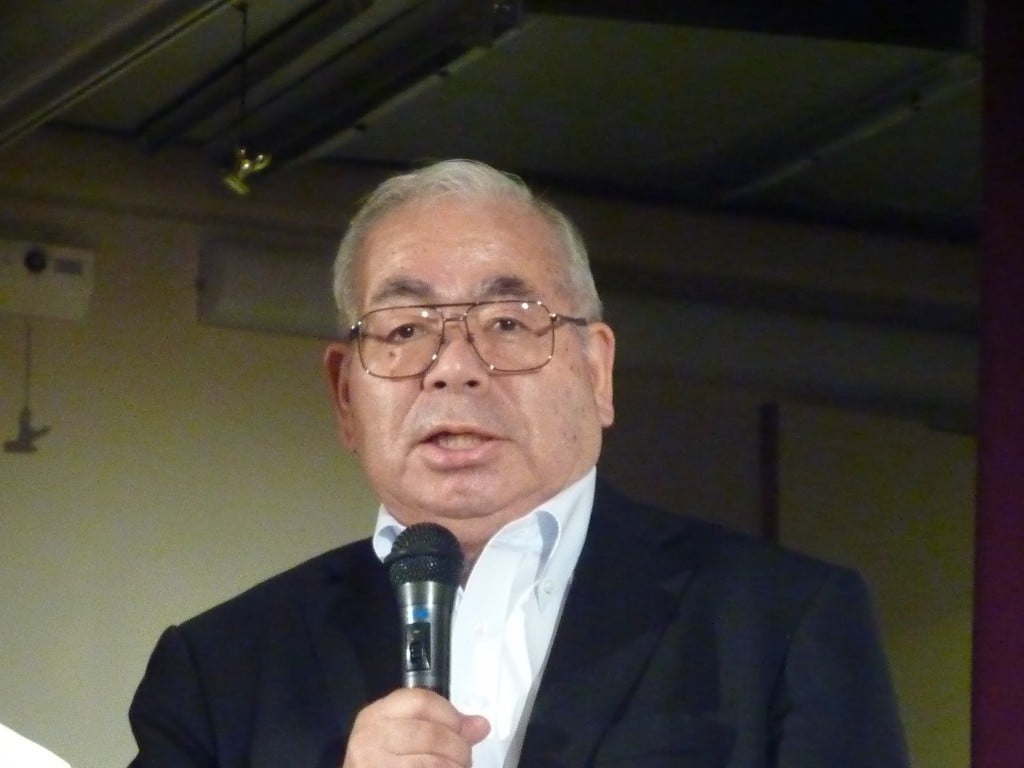

Kenzo Tomonaga has been at the forefront of the Buraku struggle since the 1960s. Though not Buraku himself, he married a resident of Sumiyoshi, a Buraku neighbourhood in Osaka, and went on to join the Buraku Liberation Research Institute in 1968, where he served as director for many years. He has witnessed first-hand the transformation of the Buraku rights movement over the last 50 years and is as aware as anyone of the hard work behind the progress that has been achieved.

At around the time that Tomonaga started to work with the Buraku movement, the Japanese government launched the Law on Special Measures for Dowa Projects. Though it made no specific mention of Buraku, favouring instead the term ‘Dowa’ (signifying ‘assimilation’), the underdeveloped and impoverished neighbourhoods typically targeted with housing and other assistance by the programme were exclusively made up of Buraku communities. This funding played a vital role in reversing the legacy of decades of public neglect in some of the most marginalized areas across Japan, bringing essential services and infrastructure for the very first time.

A portrait of Kenzo Tomonaga. The movement also took on an increasingly international dimension from the 1970s, with activists engaging United Nations (UN) bodies and mechanisms in an effort to pressure the Japanese government to adopt various human rights instruments. Tomonaga played a major role in these activities. One important milestone for the movement was the Second World Conference against Racism organized by the United Nations (UN) in Geneva in 1983. The BLL did not yet have UN consultative status but with the help of Ben Whitaker, MRG’s Executive Director at the time, they were able to give a presentation to the assembly – the first time the issue of Buraku discrimination was formally discussed at the level of the UN, and with Japanese government representatives in attendance.

Throughout this period, the Japanese government continued to operate the Dowa programme, bringing significant improvements to Buraku communities across the country. This process was instrumental in addressing many of the shortfalls in public services, housing and other visible manifestations of their exclusion. At the same time, their problems were framed largely in terms of poverty and economic development, rather than human rights and discrimination – yet many Buraku still contended with hate speech and stigmatization in their everyday lives.

If further proof was needed, reports emerged in the mid-1970s of a secret registry of Buraku neighbourhoods that corporations were using as a means of covertly blacklisting Buraku applicants from employment. While Japan’s Family Registration Act was subsequently revised to prevent third parties from accessing government-held family registries, in private the use of unofficial lists by agencies persisted, though the practice was gradually curbed in the 1980s with the passage of local ordinances in Osaka and elsewhere: these prohibited anyone from checking another individual’s background to determine their ancestry.

This demonstrates the limitations of the Japanese government’s tendency to address discrimination through money and resources without a broader engagement with the human rights issues at stake. The Dowa programme made great strides in narrowing the gap between Buraku communities and other Japanese, but it did not spell an end to hate speech and prejudice. Indeed, towards the end of the Dowa programme Tomonaga reports that it became a sticking point for right-wing groups and others hostile to Buraku, with isolated cases of corruption and mismanagement within the community being exploited to perpetuate negative stereotypes about them. Consequently, the programme had begun to be counterproductive.

March in Tokyo calling for the retrial of both the Sayama case and the Hakamada case – claiming each of them is innocent. There was relatively little action from the government on Buraku issues after the end of the Dowa programme, and in the ensuing years activists have continued to focus on community development and challenging the persistence of societal discrimination. In 2016, however, the Act on the Promotion of the Elimination of Buraku Discrimination was passed – the first piece of legislation, Tomonaga reports, to directly reference the Buraku community by name. While it represents a step forward, the act (like most anti-discrimination legislation in Japan) suffers significant shortcomings, with no criminal penalties, no clear mechanism for victims of discrimination to seek justice and no specific body responsible for implementing its conditions.

What is also needed, beyond legislation, is a wider transformation of popular attitudes and increased awareness of the exclusion that Buraku communities have experienced. The very fact that many Japanese, particularly the younger generation, are not even aware of their existence is regarded by some as a sign that anti-Buraku discrimination was a thing of the past. Yet this lack of visibility has also contributed to its persistence in other forms.

Marriage

The fact that Buraku are not visibly different to other Japanese and share the same language, faith and ethnicity does not mean that the problem of discrimination has gone away. Naoko Saito, a non-tenured Associate Professor at Osaka City University, has focused much of her research on examining how major shifts within Japanese society have reshaped, but not extinguished, prejudice against Buraku.

Naoko Saito, Associate Professor at Osaka City University. It was widely believed, she says, that discrimination against Buraku would naturally disappear of its own accord as Japan modernized. Yet social and technological change has brought new challenges. In recent years, for instance, lists recalling the old registries have been disseminated online by hate groups, making the information even easier to find. Now all that is needed to identify a Buraku neighbourhood is a good internet connection.

At the same time, for human rights researchers like Saito, the absence of a clear definition of who is Buraku and the limited data available on the community has meant that the picture of their experience today is incomplete. The government, for its part, has not conducted an official study on Dowa districts since 1993. The fact that, even after the passage of the 2016 Buraku Discrimination Act, there is no law specifically prohibiting discrimination has also meant that the government’s Human.

Rights Protection Bureau only investigates incidents of discrimination if it receives individual complaints. As it is rarely approached by victims, most cases go unreported, and even when formal claims are made these are not necessarily investigated.

Saito’s work focuses in particular on relationships, an area that like employment was long characterized by background checks: prospective husbands or wives might find themselves suddenly dropped if evidence emerged of Buraku ancestry. The situation has evolved significantly since the 1970s, according to Saito, due in part to a broader shift away from the practice of arranged marriages. Over time, as younger Japanese became more financially independent of their parents and social norms relaxed, the barriers between different communities reduced. By the 1990s, as multiple relationships before marriage became common, it was no longer openly acknowledged as a serious issue.

Rally in Tokyo on October 31, 2019, calling fro the retrial of the Sayama case – Kazuo Ishikawa is Innocent, Nevertheless, there is evidence that some stigma still remains. For example, Saito cites a 2010 survey in Yasu, a city close to Osaka and Kyoto, which asked respondents what they thought if someone’s spouse was investigated for Buraku ancestry before the marriage. While only 3.2 per cent felt it was fair to do so, compared to 71.9 per cent who said they should not, 20.4 per cent felt that it was in bad taste but necessary – a significant proportion that suggests that there is still some tacit tolerance of discrimination in Japanese society.

To develop a clearer picture, Saito has been soliciting testimonies from individuals on their experiences of discrimination. Some of these also suggest that there is still some stigma towards Buraku, especially among older Japanese. Furthermore, while there does appear to be less awareness among younger Japanese of Buraku issues – indeed, in some cases, individuals only find out about their own Buraku heritage by chance – this is not the same as a positive sense of tolerance and acceptance. The danger that, if they are discouraged by their parents from continuing a relationship with someone of Buraku descent, they may not have a sufficient understanding of the issues at stake to resist. This is all the more pertinent now, with the country’s economy in stagnation, as young Japanese are again becoming more dependent on their parents for financial support. This could leave them more susceptible to parental pressure in other areas of their lives – including whom they choose to date and marry.

Saito sees education as the ultimate solution to the problem of discrimination: this means, among other things, more space in the history books and a better understanding of human rights issues for teachers, too. Saito has been encouraged by signs of increasing engagement since the Buraku Discrimination Act was passed. She herself provides anti-discrimination training at the Osaka Prefectural Education Centre and has seen the number of teachers enrolled in these sessions soar in the last three years, from just six in 2015 to 150 in 2019. This offers the hope of a more meaningful shift in Japanese society with the next generation, moving beyond a passive silence on Buraku issues to an active understanding and respect for the community.

-

This difficult history of Japan’s Buraku population is illustrated by the case of Sumiyoshi, an area of southern Osaka home to a community dating back hundreds of years: there appears to be documentary evidence of Buraku as far back as 1284, when a nobleman refers in a diary entry to a group cleaning Sumiyoshi shrine. This work was one of the main occupations of the community over the years, along with other tasks traditionally reserved for lower castes, such as the disposal of animal carcasses and sandal making. In 1586 the community built their own temple, Shinganji, a graceful structure of dark wood and sloping roofs that still stands today.

In the early twentieth century Sumiyoshi saw some improvements, including the construction of public baths, but continued nevertheless to be characterized by poverty and exclusion. The rice riots of 1918, triggered by a spike in the cost of this staple, saw 11 residents of Sumiyoshi who participated in the protests falsely arrested as ringleaders. This may be one reason why Sumiyoshi, while continuing to develop various local intitiatives in their community, did not join the National Levellers’ Association when it was formed in 1922. This organization, the first large-scale Buraku rights group in Japan, was disbanded during the Second World War but subsequently reformed and eventually changed its name to the Buraku Liberation League (BLL).

Sumiyoshi managed to escape the Allied bombing that devastated much of Osaka, but the situation of the community in the aftermath of the Second World War remained perilous and many residents were forced to use the black market to survive. Nevertheless, in time a local branch of the BLL was formed and ultimately a new chapter for Sumiyoshi began – one where residents took an increasingly active role in the development of their community. While this approach proved divisive at first, with some fearing that any political activity could alienate the local authorities and cut off whatever benefits Sumiyoshi was receiving through them, the effectiveness of this approach was amply vindicated in the decades that followed.

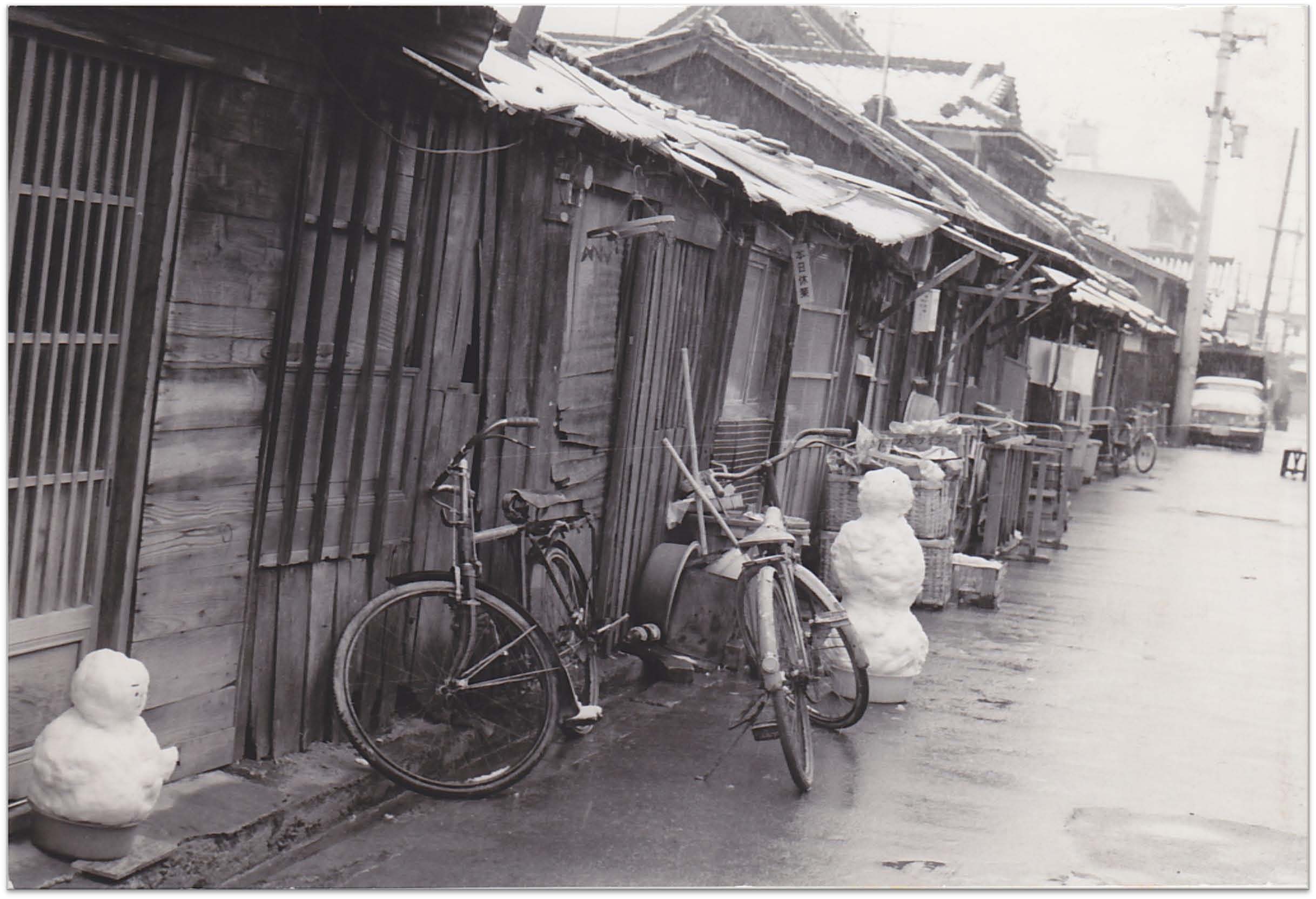

Drainage being installed in Sumiyoshi. Like many other Buraku neighbourhoods across Japan, Sumiyoshi was one of the beneficiaries of the country’s Dowa programme, beginning in the late 1960s. While housing had previously been comprised of dilapidated wooden shacks with little in the way of infrastructure, the community was steadily transformed through new housing, drainage an other amenities. Nevertheless, the revitalization of Sumiyoshi at this time owed a great deal to the progressive vision of Sumiyoshi’s residents themselves, who among other achievements established in 1973 six principles to guide the development of their community over the next decade. These included ensuring that all residents could remain there permanently and that the neighbourhood’s design reflected everyone’s needs, including children, older residents and persons with disabilities, while prioritizing human relationships and health.

Equally importantly, the plan advocated the importance of supporting not only Sumiyoshi but also other communities nearby – an approach that has helped lower the longstanding barriers separating Buraku residents from their neighbours. This is especially pertinent given its past experience of exclusion from its surrounding areas: for instance, it was not so long ago that a wall stood between Sumiyoshi and the railway that runs next to it to spare other passengers the sight of the community.

Sumiyoshi remains a thriving neighbourhood that still reflects the same values of inclusion and diversity. Even the housing built in recent years is low-rise, rarely exceeding four storeys, to ensure that social ties between community members remain strong. Nevertheless, the community, like other Buraku districts, has had to adapt to change, including the end of the Dowa programme: among other impacts, the neighbourhood’s main community centre was closed in 2010.

Modern housing in Sumiyoshi This large building was originally constructed in the 1970s with public funding and used for a range of activities, including sport and recreation for the young. By being open to all, it played a major role in building bridges with other communities. One striking illustration of this was the statement by one nearby resident who, when the centre faced closure, was one of those who petitioned local authorities to keep it open. She described how, before she started attending the centre, she had always harboured prejudices about the Buraku community: her many positive experiences meeting and interacting with residents of Sumiyoshi, however, had helped transform her beliefs.

In the last few years, the community has built a thriving new community centre that continues to provide Sumiyoshi with a valuable social space for all ages. While older residents meet regularly for mah jong and dancing lessons, younger residents attend after-school meetings and enjoy cooked meals every fortnight to ensure good nutrition. While barriers remain, with many younger residents still struggling to access employment and education opportunities, Sumiyoshi nevertheless offers an inspiring example of community-led urban transformation.

-

It is estimated that there are up to 1 million ethnic Koreans living in Japan today, almost half of whomIt is estimated that there are up to 1 million ethnic Koreans living in Japan today, almost half of whom do not have Japanese citizenship. A large proportion of this population are the descendants of migrant workers brought over, many by force, from the Korean peninsula as cheap labour during World War Two. As colonial subjects of Japan, they were coerced into changing their names and obliged to receive education within the Japanese schooling system. Hundreds of thousands remained after the end of the conflict, unable or unwilling to return, despite suddenly finding themselves reclassified as foreigners. The community now spans several generations and is spread across Japan. Though their situation has improved significantly in recent decades, they continue to suffer many forms of discrimination, and have frequently been targeted with hate speech by right-wing groups.

Though many Koreans are based in Tokyo and other cities, Osaka is home to the largest Korean population in Japan, particularly in the neighbourhood of Tsuruhashi. Here, close to the bustling shops and restaurants of Koreatown, is the office of the Korea NGO Centre. Founded in 2004, it is now one of the largest Korean organizations in the country, with a range of programmes underway to support the community’s cultural activities, combat discrimination and raise greater awareness in Japanese society about the everyday challenges they face.

Shoppers in Tsuruhashi international market. Jin Woong Kwak, one of the centre’s original founders and now its CEO, is leading much of this work. One of the greatest challenges, he says, is the limited understanding of the barriers that Koreans face in a country where they are still classified as ‘foreigners’, despite having lived in Japan for generations. Many Korean residents are reluctant to formally naturalize, since this would require them to renounce their South Korean citizenship: given their long history of colonial rule, when they were forced to deny their ethnic and cultural identity as Koreans, many now view this as assimilation. Unable to vote at a local or national level, they are left without representation in city councils or parliament.

Their lives are further complicated by the vagaries of international diplomacy in the region and Japan’s fluctuating relationship with both North and South Korea. Recent tensions between Japan and its neighbours, for instance, have contributed to a more uncertain environment for Koreans within the country. Ultimately, however, these disagreements are also rooted in unresolved disputes around Japan’s recent history and its actions in the Korean peninsula during the first half of the 20th century. In this context, the work of the Korea NGO Centre offers a platform to affirm solidarity, respect and equality within Japan and with partner organizations elsewhere, even when the mood of the region’s geopolitics is hostile.

Jin Woong Kwak (far right) at a press event in Osaka on the right of ethnic Koreans and other groups to participate in a local referendum. One of the organization’s most important lines of work is strengthening the sense of identity within the community. With limited opportunities to learn about Korean language, culture and history, not to mention the stigma of belonging to a minority, many Koreans today are disconnected from their heritage. This is often a result of deep-seated shame around their origins and the widespread pressure to assimilate into mainstream Japanese society. The overwhelming majority, for example, use Japanese rather than Korean names: indeed, Kwak recounts how he himself avoided using his Korean name when he was younger.

At the same time, the community has had to contend with the increasing animosity of right-wing groups. At present, there are few formal protections to prevent or prohibit hate speech: the 2016 Hate Speech Act, for instance, stopped short of criminalization and to this day there are no penalties in place to punish perpetrators. While there are some local ordinances in Osaka and elsewhere to prevent specific activities, such as staged disruptions by protestors outside Korean schools, there are no legal restrictions on hate speech itself and discrimination in other areas, such as housing and employment. One of the difficulties, according to Kwak, is that officials have a very limited understanding of hate speech and its impacts. In particular, many believe that any legal curbs on offensive or discriminatory language would undermine free speech – a situation that leaves Koreans with limited protections in the face of slurs or vilification.

Promoting greater awareness among other Japanese and enabling positive interactions with the Korean community is therefore a central element in creating a more tolerant and inclusive society. With this in mind, the Korea NGO Centre runs an exposure programme that delivers seminars and workshops to a wide range of people including businesspeople, human rights workers, council officials and school children. The group estimates that between the sessions they organize themselves and the various visits they make to places like schools, they manage to reach some 25,000 people every year. They also undertake a number of other programmes, such as pickle making classes, to encourage Japanese members of the public to engage directly with Korean culture.

As Koreans continue to be marginalized from many areas of public life in Japan, not least political decision making, the need for a wider shift in societal attitudes is as pressing as ever. Much of this will depend on education. The Korean community, their culture and the traumatic history of colonialism that continues to shape their experiences are at present still largely absent in the school curriculum. As Kwak points out, the first step is to consider what kind of society Japan wants in the decades to come. To what extent the country is able to navigate towards a more tolerant and inclusive future will largely be determined by what happens in its classrooms today.

-

While education is often seen as the best chance of a more inclusive future for Japan’s minorities, the issue of minority schools is currently one of the most contested in the country – with Korean schools in particular on the frontline of this debate. The most visible manifestation of this has been the harassment of Korean students by hate groups and the staging of aggressive anti-Korean demonstrations outside their schools, but these activities by a relatively small fringe are only part of a much wider picture of discrimination.

This is illustrated by the Japanese government’s new pre-school programme, rolled out in October 2019, extending free childcare for children up to the age of five at some 55,000 kindergartens and nurseries across the country: the only exceptions to this generous package were over 80 foreign kindergartens, almost half of them Korean. It was the latest chapter in a long saga of discrimination that has politicized the subject of Korean education in Japan. Today, the situation is so sensitive that many Japanese see it as a national security concern, despite the fact that the right to education for minorities is guaranteed in international law.

Wooki Park-Kim, secretariat staff person with the Human Rights Association for Korean Residents in Japan (HURAK), describes the deep sense of despondency that has resulted from this latest act of discrimination – a situation that has left the community ‘so discouraged’. Their exclusion from the waiver not only has significant financial implications: in addition, she says, ‘it affects the dignity and human rights of the ethnic Korean minority’. Nevertheless, community members are now mobilizing with the help of HURAK to build partnerships with other foreign schools to protest their exclusion.

Wooki Park-Kim and other HURAK activists at OHCHR’s headquarters in Geneva. This is not the community’s first experience of official discrimination, however. In 2010, when a similar waiver of high school tuition fees was announced – students at Japanese public schools were exempted in full and those at private schools awarded a subsidy equivalent to the cost of public education – foreign schools had to go through an application process to be included in the programme. Brazilian, Chinese and other schools were eventually able to qualify, but this was not the case for their Korean counterparts. In 2013 they were formally removed by the Japanese government from its official classification, leaving them with no avenue to secure central funding. At the same time, municipal authorities followed suit with further cuts of their own: the total allocations at prefectural level to Korean schools fell from around 550 million yen in 2010 to just 106 million yen in 2017.

As a result, the cost of attending a Korean school has become prohibitive, with tuition fees rising sharply even while teaching staff have had to take salary cuts. ‘It’s more than ten times higher than a Japanese public school and three times higher than a Japanese private school, so it’s really quite expensive,’ says Wooki. ‘That’s one of the reasons why parents are not sending their children to Korean schools, although they want to.’ She estimates that today only 10 to 20 per cent of Korean children are enrolled in Korean schools. This has had severe consequences for Korean language and culture, given their absence from the curricula of mainstream Japanese schools. While the government’s discriminatory policies have put the future of many Korean schools in jeopardy, it has shown no sign of adopting a more diverse and inclusive approach in its national curriculum.

A further barrier is the fact that, as the vilification of the Korean community by far-right groups has intensified in recent years, many young community members face increasing pressure to assimilate. Wooki attributes the rise in hate speech in part to the government’s decision to exclude Korean schools from the tuition waiver in 2010 – a policy she describes as effectively a ‘hate act’ that has helped legitimize the surge of threats and intimidation by vigilante groups against them. While hatred against the community is not new by any means and goes back decades, it has nevertheless become more visible and open. In this context, many Korean children are keen to conceal their identity and prefer to use Japanese names.

Korean school students demonstrate in front of the Ministry of Education, Tokyo. As in other areas, the issue of Korean education is overshadowed by the turbulent relationship between Japan and both North and South Korea, particularly since the revival of nuclear testing under President Kim Jong-un and the lack of resolution over the abduction of Japanese nationals by North Korean agents. Hopes were raised by an apparent thaw in relations between the countries that Korean schools would not be excluded from the kindergarten waiver, though this proved not to be the case. Yet again, the Korean community has become collateral damage in Japan’s diplomatic disputes: as Wooki puts it, the decision to exclude them was effectively a sanction.

Many in the community feel that the government ultimately wishes to bring an end to Korean education altogether, a reflection of its broader tendency to promote a homogenous Japanese nationalism despite the longstanding presence of minorities in the country. From the late 1940s, when efforts to close Korean schools first began, there were more than 500 across the country, and since then the numbers have reduced steadily to just 66 today. Without financial support or a shift in the political rhetoric currently employed against them, the decline of Korean education in Japan is likely to continue.

HURAK and other activist groups remain active both within Japan and internationally, regularly lobbying at the UN for the Japanese government to respect the right to education for minorities enshrined in international law. At the same time, as Wooki highlights, their efforts focus on transforming attitudes within Japan towards Korean education. ‘This is not a political issue, but a human rights issue,’ she says. ‘That is what our organization is saying to Japanese society.’

-

The challenges of assimilation and invisibility in Japan are starkly illustrated by the recent history of the Ainu community. Indigenous to the northern islands of Hokkaido, for centuries they maintained a lifestyle of hunting, fishing and foraging until the wholesale occupation of their land. Unfamiliar diseases, a coercive colonial administration and an influx of Japanese settlers from the mainland proved devastating to the Ainu and their way of life. In the ensuing years, along with the dispossession of their land, the Japanese government imposed a raft of measures including a prohibition on the use of Ainu languages, compulsory education in Japanese and an end to their traditional livelihoods. Amazingly, the 1899 Hokkaido Former Natives Protection Act, a paternalistic piece of legislation that encouraged their assimilation into Japanese society by promoting farming and the establishment of schools, remained in place for almost 100 years.

Ainu man and woman outside in ceremonial attire for the Marimo festival in Shiroai, Hokkaido, Japan. 8 October 1961, Archival photo. The Ainu Association of Hokkaido was founded in 1946, in the aftermath of World War Two, with the aim of reversing this long process of assimilation. Initially the organization focused on domestic advocacy, pressuring the Japanese government for recognition of their community, but with little or no response. Indeed, until 1991 the government did not even recognize Ainu as an ethnic minority, let alone an indigenous people with specific rights and territorial claims.

Yupo Abe, deputy head of the organization, has spent decades researching and campaigning for Ainu rights. During this time he has seen the government’s position slowly shift – from refusing even to acknowledge Ainu as a distinct community to apparent recognition of their indigenous status. He credits the decision to take their struggle beyond Japan as a decisive moment in the evolution of the Ainu movement. Besides bringing much needed visibility to an issue that few within Japan were willing to confront, the engagement with other indigenous peoples and representatives provided the Ainu representatives with a deeper awareness of their own situation.

There was little understanding, Abe says, of the concept of indigeneity in Japan, even among Ainu themselves, and the discussions with other indigenous peoples’ organizations which had been mobilizing for decades to demand recognition of their rights were revelatory for him and other activists. This dialogue helped resensitize them to their own identity as an indigenous people and the realization that their rights had been systematically violated. From the early 1980s, in the absence of government engagement with international mechanisms, the Ainu Association began to engage various UN platforms directly. Abe describes how this process culminated in their participation in the UN Working Group on Indigenous Peoples in 1987 and their subsequent submission to the Japanese government, around the time of the 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, of the International Labour Organization’s questionnaire for states on their indigenous populations. When, as might have been predicted, they received no response, they filled out the answers themselves. The Ainu Association subsequently sent delegates and in 1992 the then President of the Association delivered an address at the UN.

Yupo Abe delivering a presentation to the IMADR General Assembly. By the late 1990s, attitudes in Japan had begun to change. In 1997, the government finally replaced the antiquated 1899 law with the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act – a step forward that nevertheless left much to be desired, particularly in its lack of any mention of rights to land, resources or political representation. So, while the local government in Hokkaido began to roll out targeted initiatives to address poverty and exclusion in Ainu communities, the focus was on levelling social disadvantage, not respecting human rights or ending discrimination. In 2008, another milestone was reached with the passing of a parliamentary resolution affirming Ainu as an indigenous people of Japan. However, while delivering an important victory, this declaration still stopped short of legal recognition and was seen by some community members as largely symbolic.

The passage in 2019 of a bill finally grating legal recognition to the Ainu as an indigenous people, with provisions to promote their inclusion and support their traditional culture, was heralded as a major breakthrough for the community in much of the media coverage at the time. Yet as Abe makes clear, the reality is more complex and the bill has proved divisive within the community. Many members point to the notable gaps in the bill – in particular, the absence of concrete commitments to return land, resources or political control to the Ainu.

As Abe freely admits, these criticisms are valid: the lack of clear guarantees of restitution in the text mean that for now it amounts to recognition in name only, and falls far short of the terms stipulated by international law. And while Hokkaido makes up just over a fifth of the total area of Japan’s territory, around half is state-owned and includes large swathes of undeveloped natural resources such as coasts, rivers and mountains. If Japan was serious about offering adequate compensation to the Ainu, in line with the recommendations made by UN bodies as such as the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, it could deliver a great deal more than is currently offered in the bill.

Despite these reservations, Abe is still hopeful the bill could bring further change. In addition to the establishment of a ministerial council and provisions on non-discrimination – even if the latter lack actual sanctions – the bill includes a five-year review that will provide the opportunity to revise it further in line with international standards. He cites the example of Taiwan, where legislation on indigenous rights has been able to evolve as societal understanding of these issues has steadily improved. Consequently, he welcomes the law as a valuable step in the right direction, but will continue to advocate for further reforms in the years to come.

In the meantime, Ainu activists are focusing on the revival of their identity with cultural initiatives, community education and schools offering lessons in the now critically endangered Ainu language. These activities have as important a role to play as legal reform after many decades of state-sponsored assimilation. At the same time, given that Ainu are largely absent from the history books, there is an urgent need to educate other Japanese on their country’s indigenous heritage. Today, even among academics, many are unaware or unwilling to acknowledge that their past and present extend beyond the nationalist narratives of a single, monolithic Japan. Until this story changes, the Ainu struggle for recognition will continue.

-

Ryukyuans, also known as Okinawans, have inhabited Okinawa through a long and often difficult history that has included colonial rule and occupation. Though previously claimed by the Japanese shogunate in the early seventeenth century, it also remained a tributary of the Chinese emperor and was formally annexed by Japan until 1879. This was the beginning of a much harsher era of assimilation and coercion by the Japanese government, with widespread expropriation of land, repression of traditional cultures and a strictly enforced ban on the use of Ryukyuan languages. This period culminated in the devastation of the islands during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945 and the death of as much as a third of the civilian population.

In the aftermath, Okinawa was controlled by the US military until 1972, long after the signing of the 1951 San Francisco Treaty that returned sovereignty to Japan. During this period, large swathes of agricultural land were redeveloped into army and naval bases. Even after the territory was formally returned to Japan, the US retained a significant foothold in Okinawa. Today, the US military still occupies around a fifth of the territory in the islands.

This situation has created a wide range of problems for local residents, from crime and accidents to noise and pollution, and hopes that the military presence would gradually decrease over time have been disappointed. Indeed, the issue has become especially fraught in recent years amidst plans to relocate the US military base in Futenma to Henoko, a biodiversity hotspot that hosts an array of marine species, including the endangered Okinawan dugong. Local resistance to the relocation is strong – 72 per cent of voters in a non-binding referendum in February 2019 voted against it – but the Japanese government is pushing through with the plan regardless.

Anti-war fence at Henoko beach near Camp Schwab, Nago, Okinawa, Japan Their predicament occurs against a wider backdrop of discrimination that includes the continued decline of Ryukyuan languages, some of which are now classified as severely endangered by UNESCO. Economic deprivation is also widespread: one in four households with school-age children are living in poverty and unemployment in Okinawa is almost twice as high than the rest of Japan. In this context, almost a quarter of Okinawans are now living on the mainland, driven in many cases by the search for work. The lack of livelihood opportunities in Okinawa itself, despite a tourism boom, is due in large part to the destruction of much of the best agricultural land to accommodate military development. Other impacts arising from the protracted military presence, highlighted by the Association of the Indigenous Peoples in the Ryukyus (AIPR) in its submissions to the UN, include environmental destruction, sexual violence and arbitrary detention of peaceful activists.

Finally, unlike Ainu, Ryukyuans have yet to be recognized as an indigenous people in spite of their longstanding ties to their territory, rich cultural traditions and linguistic diversity – features now threatened by the control exerted over the islands by the central government and the continued occupation of the US military on much of their land. Despite many similarities with the experiences of the Ainu population, who themselves until recently were not acknowledged as indigenous by the Japanese government, to date there has been no progress in terms of their recognition. Securing official acknowledgement of their status as an indigenous people would be a significant step in redressing the injustices suffered by the community – but at present, official policy appears to be heading in the opposite direction. In the words of AIPR, ‘Japan is not only failing to protect or promote the rights of the indigenous peoples in the Ryukyus, but also expanding the military usage of the lands of the peoples in the Ryukyus by promoting construction of new military facilities.’

-

With falling fertility rates and an ageing population, Japan’s demographic challenges are especially acute. Around 28 per cent of the national population are now 65 or older, a proportion that is set to rise further in the coming years while the number of younger Japanese declines. As a result, there is likely to be a growing need for foreign workers to fill the gap. Yet to date, in a society that has traditionally seen itself as homogenous and self-contained, immigration remains a divisive issue.

A new visa system, facilitating the arrival of up to 345,000 immigrants over the next five years, came into effect in April 2019. This policy, the first time the Japanese government has publicly acknowledged the need for immigrant labour, sparked widespread resistance across the political spectrum. Many lawmakers expressed fears that migration on this scale would undermine Japanese identity and pose a threat to national security.

Activists taking part in a demonstration for foreign workers’ rights. This is despite the fact that immigration to Japan has been ongoing for more than a century, beginning with the colonization of the Korean peninsula and the subsequent importation of over a million Koreans as labourers, often by force, by the end of the Second World War. Many of their descendants, even those resident for multiple generations, are still classified as ‘foreigners’ – a situation that reflects the country’s contradictory attitude to its minorities. More recently, in the early 1990s, Japan permitted the arrival of hundreds of thousands of Brazilians and Peruvians of Japanese descent, known as nikkeijin. Shortly after, in 1993, the Technical Intern Training Programme (TITP) began: this initiative, presented as an opportunity for citizens in neighbouring countries such as China and Vietnam to gain work experience and professional development opportunities in Japan, remains in place to this day.

The new law, for all the controversy it has generated, does not in fact represent a fundamental shift in the government’s attitude to immigrants: its architect, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, has himself stated that ‘this is not an immigration policy’. It does not contain any provisions to strengthen protections for migrants, for example, nor extend their limited rights to education and health care. Ultimately, it continues a long political tradition in Japan of viewing immigrants as an expediency, to be used as needed without welcoming them as long-term residents, let alone citizens.

According to Makiko Ando, Deputy Secretary-General of the Solidary Network with Migrants Japan (SMJ), the Japanese government has tended to regard its migrant population as an expendable resource and generally felt little responsibility for their wellbeing while in the country. This was evident back in 2009 when, in the wake of the global financial crisis and widespread job loss, the government offered nikkeijin – resident in Japan for almost decades and overseeing some of the dirtiest, most demanding work – a one-off payment to leave. Now, too, as demand for labour gears up ahead of the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo and beyond, Ando says that the government is focusing on how to bring in ‘fresh, young’ immigrants while taking steps to remove many migrants who have been resident in Japan for a long time, particularly those who are currently undocumented. ‘The Japanese government,’ says Ando, ‘thinks, “They are undocumented – they violated the law. We will get a new labour force so we don’t need them anymore.”’ The government, she adds, ‘sees them like criminals’ – hence its plans to promote a ‘clearance’ ahead of the Olympics.

Given the lack of official support and protection, SMJ was founded in 1997 to champion migrant workers and advocate for greater recognition of their contribution to Japanese society. More than two decades on, however, many of the same barriers remain – not only issues around labour exploitation, such as unpaid wages, long hours and dangerous working conditions, but also broader challenges around hate speech, exclusion and invisibility. Migrant women, in particular, are especially vulnerable to sexual harassment from their employers and are also exposed to high levels of domestic violence. These are complex problems that require a range of responses, from counselling and health care to legal assistance and public advocacy. Fortunately, SMJ brings together a wide range of stakeholders, from academics and lawyers to politicians and activists, who contribute their expertise to its various programmes.

‘I am making your convenience store’s bento!’ An activist holds a placard at the march. While a significant part of its activities focus on addressing the day-to-day needs of migrant workers, such as access to education and health care, SMJ also plays a leading role in lobbying on their behalf with the Japanese government. One of their central objectives is the abolition of the TITP programme, until now one of the main gateways for foreign workers to enter Japan. Hundreds of thousands of ‘technical intern trainees’ have been brought into the country through the scheme, lured by the promise of training and career development within a Japanese company. The reality, however, typically falls far short of their expectations, and recruits are often tasked with very different duties to those agreed in their contracts. Frequently overworked and underpaid, many also suffer other human rights violations including verbal abuse, physical violence and sexual assault.

Similar in some respect to the difficulties facing foreign labourers in the Gulf, migrant workers entering Japan through TITP typically sign a contract that ties them to a single employer, and can face imprisonment, fines and deportation if they try to find work elsewhere. This leaves them with few options if they experience misconduct or harassment. The situation is not aided by the fact that trainees are recruited through a complex arrangement between brokers and sending organizations in their country of origin, on the one hand, and supervising agencies and companies on the other. This creates an opaque and unaccountable system that can easily enable exploitation.

This is illustrated by the restrictions that migrants, particularly women, face when it comes to relationships and sexual activity while in Japan. In principle, Japanese law is clear on this issue: not only are migrants free to pursue relationships, like anyone else, but any attempt by their employers to prevent them from doing so is itself a crime. In practice, however, many migrant workers face pressure to fall in line with these expectations. According to Ando, while the formal contracts signed between recruits and their Japanese employers do not mention penalties for workers if they fall pregnant, the contracts signed with their brokers in their country of origin may include other stipulations along these lines. She cites the example of one Chinese migrant whose contract with her Japanese employer amounted to three pages, but was also forced to sign another contract in Chinese with her sending organization that was almost three times as long – and included, among other provisions, a ban on relationships and the threat of deportation if she became pregnant.

The effect this has in the lives of migrants can be tragic. One case that Ando has been engaged in involved a young Chinese woman who, after she gave birth, abandoned her baby because she feared that otherwise she would be deported from Japan. She was currently being held in a police station, after being linked back to the baby, who was still in social services and had yet to be reunited with its mother. In another case a Chinese woman, after falling pregnant, was told to go home. She was then taken to the airport but managed to get in touch with her boyfriend using a stranger’s mobile phone at the airport before she boarded the plane: many others, however, have been forced in similar circumstances to leave the country.

Another problem that TITP migrant workers experience is that, having been recruited for a specific role or sector, they find on arrival that they are tasked with something else entirely – work that is often much more dangerous or demanding that what they signed up for. Notoriously, this has included trainees being assigned decontamination duties after the nuclear disaster in Fukushima and other areas affected by radioactive waste. In this instance, following a number of well-publicized incidents where migrants had been compelled to engage in this work, SMJ and others successfully lobbied the Japanese government to ban the use of TTIP trainees in decontamination work.

In general, however, Ando reports that the government has been reluctant to engage with SMJ and other civil society groups on these issues. There is still no dedicated, adequately resourced body responsible for identifying and responding to violations of migrant rights, nor much in the way of data collection or consultations with migrant workers themselves. What information the government has gathered, however, mainly through employers rather than migrants, suggested widespread and continued violations: a recent survey of companies employing technical intern, for instance, found that more than 70 per cent had committed violations of labour laws such as excessive working hours, inadequate safety measures and unpaid overtime. An added problem is that, when data is available, the government has often drawn the wrong conclusions. An official survey of TITP recruits two years before, for example, found that some 86 per cent of technical intern trainees who had disappeared from their workplaces had done so to find a better salary elsewhere. This was taken to suggest that the decision was largely economic, but this ignored the fact that 67 per cent of the technical intern trainees in question were also being paid less than the minimum wage, making it a human rights issue.

Activists participate in the annual March in March in Tokyo, calling for equality and human rights for foreign workers. Echoing previous statements by the UN, Ando describes the current TITP programme as a system of ‘official trafficking’. While some have called for the TITP programme to be reformed, as far as she and other colleagues at SMJ are concerned there is one option only – to bring an end to the system in its entirety. ‘We want to abolish it’, Ando explains. ‘The whole system is wrong’. She points to the fact that, while some amendments to the system were made back in 2017 to prevent abuses, there has been little sign of improvement. A programme that has presided for more than 25 years over protracted and systematic human rights violations cannot easily be retrofitted into a humane migration platform.

Ultimately, though, the problems extend beyond the TITP to the wider issue of how Japan continues to view immigration. Given that the new migration policy replicates many of the worst aspects of TITP, such as the restriction on changing their workplace, it is likely that the exploitation and abuse of foreign workers will continue in the years to come. While the policy has provoked much debate, says Ando, this has primarily focused on the question of numbers and whether the 345,000–person quota is too little or too much. SMJ, on the other hand, believes this is not the most important issue. Rather than having a position on what levels of immigration the country should have in future, the organization is calling for a greater focus on ensuring that whatever migration does take place is well organized, grounded in human rights and – above all – places the needs of migrants themselves at the heart of this process.

In the meantime, with SMJ’s support, foreign workers continue to advocate for recognition of their place in Japanese society. Each year, during the ‘March in March’, hundreds of migrants fill the streets of Tokyo to protest their exclusion. Despite everything, says Ando, the demonstrations are generally a highlight for those taking part. For a group whose lives are generally spent on the sidelines, it is a rare opportunity to be seen and heard.