Minority and Indigenous Trends 2021: Lessons of the Covid-19 pandemic

It was clear, even in the early days of the pandemic, that minorities, indigenous peoples and other marginalized communities were at greater risk of infection and death from Covid-19. This was for a variety of reasons, ranging from limited access to health care and a higher prevalence of pre-existing illnesses to poverty and the concentration of many members in jobs and livelihoods that were hazardous or insecure.

Indeed, across the world, many frontline occupations such as delivery services, public transport and medical work are undertaken by members of these communities, working continuously throughout the first lockdowns when the rest of the population were being urged to stay at home for their own safety.

Subsequently, however, it has become apparent that the impacts of the crisis have extended far beyond the immediate health outcomes, with everything from employment and education to housing and mental well-being disrupted. In these areas, too, minorities and indigenous peoples have frequently borne a disproportionate burden, exacerbated in many countries by poorly implemented or discriminatory government policies. While the shared crisis of Covid-19 could have created momentum for solidarity and ceasefires, in reality persecution and conflict often appear to have escalated in the wake of the virus.

More fundamentally, however, much of the inequity and discrimination brought to the surface by the pandemic was present long before the outbreak – and is likely to remain in place without transformative societal change. As countries navigate the uncertain path towards recovery, it is vital that there is more than simply a return to normality. This painful global emergency also offers an opportunity to achieve lasting change to the systemic racism and injustice that minority and indigenous communities have contended with for generations. Without meaningful action to address these underlying issues, however, the world will continue to be exposed to the threat of further health crises in the years to come. With that in mind, this report outlines 10 key lessons for governments, societies and communities to follow for a fairer and more sustainable post-pandemic future.

Summary and thematic chapters

- 01

Executive Summary

It was clear, even in the early days of the pandemic, that minorities, indigenous peoples and other marginalized communities were at greater risk of infection and death from Covid-19. This was for a variety of reasons, ranging from limited…

0 min read

- 02

Foreword

by Tlaleng Mofokeng, UN Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health As the demands of the pandemic have evolved, from the initial scramble for masks and…

1 min read

- 03

Preface

By Joshua Castellino and Claire Thomas This report primarily focuses on minority and indigenous communities and their experiences during Covid-19. But we also turn our gaze inward briefly. In seeking to come to terms with the loss and the…

1 min read

- 04

Human rights and Covid-19: Repression and resistance in the midst of a pandemic

By Nicole Girard Covid-19 has exposed the stark inequalities existing in our societies. Minorities, indigenous peoples and migrant communities have been hit disproportionately by the spread of Covid-19, fuelled by poorer pre-existing…

1 min read

- 05

Livelihoods and employment: The impact of Covid-19 on the economic situation of minority and indigenous workers

By Rasha Al Saba and Samrawit Gougsa Amid a global recession triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic, minorities and indigenous peoples have been hit especially hard in the world of work. Not only have members of these communities lost their…

1 min read

- 06

Recognizing the right to health for minorities and indigenous peoples: Transforming the global inequalities of the pandemic into health justice

By Sridhar Venkatapuram The announcement by the World Health Organization (WHO) in January 2020 of a new and harmful infectious disease rightly raised the alarm among minorities and indigenous peoples around the world. Their concern,…

1 min read

-

It was clear, even in the early days of the pandemic, that minorities, indigenous peoples and other marginalized communities were at greater risk of infection and death from Covid-19. This was for a variety of reasons, ranging from limited access to health care and a higher prevalence of pre-existing illnesses to poverty and the concentration of many members in jobs and livelihoods that were hazardous or insecure.

Indeed, across the world, many frontline occupations such as delivery services, public transport and medical work are undertaken by members of these communities, working continuously throughout the first lockdowns when the rest of the population were being urged to stay at home for their own safety.

Subsequently, however, it has become apparent that the impacts of the crisis have extended far beyond the immediate health outcomes, with everything from employment and education to housing and mental well-being disrupted. In these areas, too, minorities and indigenous peoples have frequently borne a disproportionate burden, exacerbated in many countries by poorly implemented or discriminatory government policies. While the shared crisis of Covid-19 could have created momentum for solidarity and ceasefires, in reality persecution and conflict often appear to have escalated in the wake of the virus.

More fundamentally, however, much of the inequity and discrimination brought to the surface by the pandemic was present long before the outbreak – and is likely to remain in place without transformative societal change. As countries navigate the uncertain path towards recovery, it is vital that there is more than simply a return to normality. This painful global emergency also offers an opportunity to achieve lasting change to the systemic racism and injustice that minority and indigenous communities have contended with for generations. Without meaningful action to address these underlying issues, however, the world will continue to be exposed to the threat of further health crises in the years to come. With that in mind, this report outlines 10 key lessons for governments, societies and communities to follow for a fairer and more sustainable post-pandemic future.

Photo: A portrait of a man from the Khomani San of Kalahari community in South Africa. The reduction in tourism due to Covid-19 has impacted the community’s livelihoods. Credit: Tim Wege / Alamy.

-

by Tlaleng Mofokeng, UN Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health

As the demands of the pandemic have evolved, from the initial scramble for masks and ventilators to the ongoing struggle to purchase vaccines — one that, predictably, the most affluent states have dominated despite the urgent need in many developing countries — there has been a great deal of discussion on how to ensure an equitable recovery. Quite rightly, much of this has focused on the wide gaps between richer and poorer nations. Yet it is just as important to ensure that similar disparities do not emerge within countries between more and less privileged groups.

From early on in the pandemic, it was clear that Black people, minorities, indigenous peoples and other racially and religiously persecuted groups were significantly more exposed to the threat of Covid-19 and greatly impacted by it. For them, however, the health crisis did not begin with the virus. Within the Global South, and deeply rooted in historical oppression, coloniality, systemic racism and structural discrimination, countries have less favourable health systems and face disparities and inequities to access the determinants of health. It is in this context that those populations in particular are affected by higher rates of infant mortality to lower life expectancy, from greater exposure to communicable disease like tuberculosis to a heavier burden of mental illness. Every stage of their lives has been characterized by disproportionately poorer health outcomes. The situation is especially acute for women, people with disabilities and LGBTQ+ and gender diverse persons, who often experience intersectional discrimination on account of their identity.

These disparities are not going away on their own. We are far away from a scenario of an equitable, global vaccine rollout that successfully reaches the many communities usually excluded from underlying determinants of health such as clean water and sanitation, let alone medical care. However, without this, of course, there is no guaranteed end in sight to the pandemic. Looking beyond our immediate predicament, there are broader lessons to be learned. Otherwise, for populations in the Global South, Black people, minorities, indigenous peoples and other discriminated groups, the crisis will simply continue in other forms – exposing them, as before, to disproportionate levels of death, disease and mental illness.

We now know that many factors can contribute to better protection from Covid-19, from effective hygiene and social distancing to safer working conditions. Though often described as ‘behaviours’, these are grounded in rights and needs – adequate housing, healthy occupational and environmental conditions, labour protections, equitable health systems – that are simply unattainable for many. Unless a rights-based approach is employed for communities forced to the margins, living in crowded apartments in low-income neighbourhoods or informal settlements without sanitation, these issues will remain long after the pandemic has ended.

The crisis of Covid-19 may be unprecedented, but the inequalities it has compounded have been with us for generations. The scale of the challenge we now face and the universal threat it poses demand much more than charity: to emerge from this catastrophe stronger, we need transformative change. This means, first and foremost, to address coloniality, an end to discrimination, inequality and other underlying conditions that have long undermined the health and security of minorities, indigenous peoples and other neglected groups. We need to fully embrace all human rights.

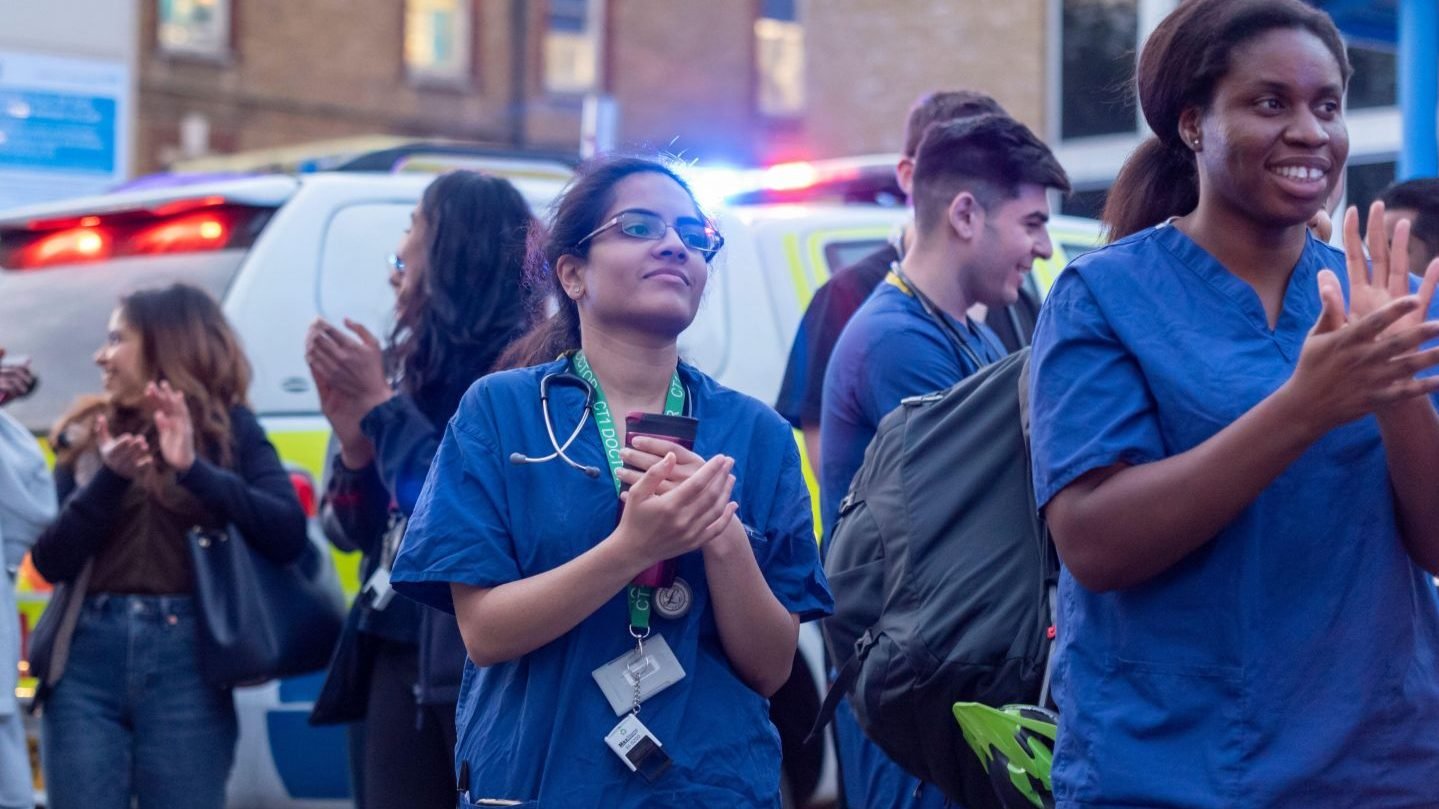

Photo: Ethnic minority health works gather with police and fire crews outside a hospital in London, UK, to ‘Clap for Carers’ as a sign of gratitude for the services of essential workers during the Covid-19 pandemic. Credit: Avpics / Alamy Stock Photo.

-

By Joshua Castellino and Claire Thomas

This report primarily focuses on minority and indigenous communities and their experiences during Covid-19. But we also turn our gaze inward briefly. In seeking to come to terms with the loss and the trauma inflicted by the pandemic, it is incumbent on us all to extract the painful lessons emerging from this experience to be better prepared for similar crises in future.

Our work at Minority Rights Group (MRG) interacts with many systems: international human rights mechanisms, development and aid provision, national advocacy and law making, judicial processes, service delivery and civil society solidarity. All of these were affected in some way by Covid-19, forcing us to rethink ways of working which, it turned out, were often dictated by habit and custom rather than necessitated by external realities.

One lesson we take away from this time is how to overcome our own resistance to change. Some ways of doing things may have changed permanently; others may revert back eventually (with or without good reason). Covid-19 highlighted how poorly designed systems were rendered ineffective in responding to a swift global challenge of this kind. In particular, it demonstrated how easily local, national and international solidarity broke down in the face of adversity. When faced with crisis, it seems, we mostly put our own needs first. Those with greater social, political or economic capital ‘won’ against those with lower status, who were less well connected or less well off. Combating these recurring patterns lies at the heart of the minority and indigenous rights and anti-discrimination mission that MRG exists for.

Prior to the pandemic, international human rights mechanisms had strongly resisted virtual participation in forums and debates. After initial postponements and cancellations, these objections were swept away and virtual participation is now routine. This has made involvement more egalitarian and cost effective but has also heightened the digital divide. Internet connectivity and equipment is not yet in place for all — with minority and indigenous communities disproportionately affected. Virtual attendance also fails to replicate the access to decision makers that ‘corridor’ lobbying normally provides, by speaking to decision makers face-to-face on the margins of physical meetings. It remains to be seen how this will settle post-pandemic. Retaining the benefits of virtual participation alongside some of the benefits of physical attendance may require designing virtual opportunities that simulate corridor lobbying online.

As an organization primarily funded to deliver restricted projects, we faced the challenge of needing to renegotiate a large number of contracts to pivot work into new directions as the original interventions were no longer possible, relevant or appropriate. This generated significant workload burdens and also led to delays in rolling out our responses. A more appropriate ‘disaster preparedness’ contract provision would have allowed donors to remove restrictions from a small proportion of restricted funding, limiting activities to the charitable objectives of the recipient organization or to project objectives without need for lengthy renegotiations. Such a mechanism could be triggered at the discretion of the donor during a global or national emergency, providing a swift, efficient and effective response by those who already have partnerships in place and are actively working to respond within their means to a crisis as it unfolds.

As the pandemic has highlighted, MRG’s work needs to continue whatever the conditions we face since our communities of concern will inevitably be pushed behind. It is therefore imperative for us to find innovative and effective ways to maintain the struggle, supporting marginalized communities and influencing institutions and the wider public until the systemic discrimination highlighted in this volume is a thing of the past. We hope the contents will provide you with insights, information, inspiration and motivation to join and accompany us on what is still a long and much needed journey towards equality, inclusion and participation for all.

Photo: Migrant workers carry their belongings as they walk along a road to return to their villages, during a 21-day nationwide lockdown to limit the spreading of Covid-19, in New Delhi, India, March 26, 2020. Credit: REUTERS/Danish Siddiqui.

-

By Nicole Girard

Covid-19 has exposed the stark inequalities existing in our societies. Minorities, indigenous peoples and migrant communities have been hit disproportionately by the spread of Covid-19, fuelled by poorer pre-existing health indicators, economic disenfranchisement and discrimination. But in many cases, it has been the government response to the pandemic that has exacerbated existing discrimination, leading to increased insecurity and direct threats to minority and indigenous rights.

While temporary and balanced restrictions are necessary to address virus transmission, these public health measures must be carried out in proportionate, rights-respecting, non-discriminatory ways. What many communities have witnessed since the onset of the pandemic, however, has been repression – heavy-handed measures that were often not conducive to protecting public health, or even counterproductive to these aims, many either targeting minorities and indigenous peoples directly or impacting on them disproportionately.

These restrictive new measures have been undertaken often by emergency order or decree, with limited oversight, infringing on a broad range of human rights and often implemented in a discriminatory manner. Freedom of movement restrictions and associated fines have frequently targeted ethnic or religious minorities and other marginalized communities in particular. Blanket bans on freedom of assembly were implemented in scores of states worldwide, including those intended to stop minority protests, as in Turkey.

Contact tracing apps are threatening privacy rights, particularly for marginalized communities that have few options but to use them, such as migrant workers in Singapore, whose return to work entailed the non-optional use of sketchy contact tracing apps. Sweeping changes have been made in many countries without clear scientific justification or an exit strategy, and without engaging vulnerable communities or mitigating potential negative impacts.

This chapter will look at how a biosecurity response to the pandemic has exacerbated the impact of Covid-19 on minority, indigenous and migrant communities. This approach further entrenches inequality by prioritizing socio-economic and political interests, viewing people only as potential carriers, and enforcing top-down, authoritarian and military interventions to ensure public health compliance. There is little consideration of the complicated impact these measures have on people facing intersectional discrimination and, in some cases, the pandemic has been used as a pretext to further undermine minority and indigenous rights protections.

At the same time, biosecurity approaches have been a catalyst for community organizing unseen on such a broad scale in decades. Minority and indigenous communities are calling for a rights-based approach to the pandemic that puts systemic discrimination front and centre to address the underlying reasons for its spread, stepping in to assist their communities where the government has failed to do so, and resisting oppressive measures implemented under the cover of Covid-19.

Quarantining communities in Bulgaria: Discriminatory measures against Roma neighbourhoods

Racist and discriminatory approaches to public health during the initial spread of Covid-19 resulted in segregation and restrictions on movement for entire neighbourhoods and settlements, as was the case for Roma in Bulgaria and Slovakia, and refugee camps in Greece, where lockdowns targeted residents while the rest of the country had returned to normal. Non-governmental organization (NGO) Médecins Sans Frontières called the extended lockdown for refugee camps ‘absolutely unjustified from a public health point of view – it is discriminatory towards people that don’t represent a risk and contributes to their stigmatization, while putting them further at risk’ by keeping them in overcrowded and unhygienic conditions.

In Bulgaria, the extreme right Bulgaria National Movement (VMRO) exploited the crisis in what some Roma rights activists described as the ‘ethnicization of the pandemic’. In the early days of the emergency, VMRO chairperson and Bulgarian Member of the European Parliament (MEP) Angel Dzhambazki called for the closure of Roma neighbourhoods, describing them as ‘real nests of infection’. Shortly afterwards, the Kvartal Karmen settlement in the town of Kazanlak was blockaded, exits to the neighbourhood were sealed and the one remaining access point was continuously guarded by law enforcement. Similar checkpoints were installed around Roma settlements across various municipalities, leading to an overwhelming presence of soldiers, police and drones – constituting a far more visible presence than medical workers and supplies. In some instances, authorities did not ensure that blockaded communities had access to food, water or medicine: in Tsarevo, for example, 500 Roma residents were left without water for 10 days. Similar blockades were not instituted in non-Roma neighbourhoods, and churches remained open.

As blockades and checkpoints continued, Roma citizens began protesting in Sofia in mid-April 2020. Working largely in informal industries, many could not provide the documents necessary to allow them to pass through checkpoints. Rumours that Roma in certain neighbourhoods were infected prompted employers to fire workers. Roma activists submitted a citizens’ petition to the two other Bulgarian MEPs, calling for them to refute the words of Dzhambazki, but were met by silence. After sustained pressure, the restrictions were lifted at the end of April. Finally, in mid-May, two UN Special Rapporteurs on racism and minority issues released a joint statement calling the actions of the Bulgarian authorities ‘discriminatory’, ‘overly-securitized’, and ‘a violation of Roma’s right to equality and freedom of movement’ through ‘a government response to Covid-19 that singles out Roma’.

Stay-at-home orders in South Africa: Black women faced a surge in gender-based violence

As governments began to acknowledge the gravity of the emerging health crisis, lockdown policies were rolled out with varying degrees of severity worldwide. Some manner of lockdown was likely necessary at this stage to effectively contain the virus, but the disproportionate impact on vulnerable communities was often not considered, nor the effectiveness of standardized preventive measures in certain contexts. For example, for remote indigenous communities that were prevented from gathering forest products, such as in Cambodia, it is questionable whether restricting these livelihood activities would have any impact on spread that was at the time concentrated in urban settings. Similarly, nomadic pastoralists were prevented from making their traditional movements between Mauritania, Senegal and Mali, resulting in lack of land to graze their animals; this led, in turn, to overgrazing and increased tensions with settled communities. Lockdowns are more challenging for already vulnerable groups, resulting in an accumulating ‘health debt’ that is compounded by loss of income, mental health problems, discontinuity of any support systems and inadequate or non-existent social protection mechanisms.

Gender-based violence in particular skyrocketed during lockdown, with nearly every country in the world reporting an increase in calls to domestic violence hotlines and women seeking help in shelters and from the police. In some countries, such as Zimbabwe, women’s shelters were not recognized as essential services; this meant that survivors struggled to reach them as they could not get the essential services permits necessary for travel to access help. In any case, service providers had to close on account of their being classified as non-essential. For minority and indigenous women and girls, this situation is compounded by the discrimination they face both on account of their gender and as members of marginalized communities. They are frequently more vulnerable to violence than majority communities, stemming from a myriad of factors including socio-economic struggles, lack of engagement by state support systems and intergenerational trauma. Many of the statistics on reported incidents of male violence against women during lockdown do not disaggregate for ethnicity or other factors, but anecdotal evidence suggests that existing patterns of violence against minority and indigenous women were magnified both during lockdowns and in their wake. For instance, a community group working with indigenous San in the Omaheke region of Namibia reported that domestic violence had increased as a result of stay-at-home policies. When San farm labourers were dismissed without pay in March 2020, the resulting tensions and frustrations led directly to an escalation in domestic violence.

South Africa, one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a woman, had one of the strictest lockdowns in the world. Patterns of violence in this country expose poor Black women to disproportionate levels of violence, including femicide. After a nine-week lockdown was eased, murders of women took a significant leap, with 21 mostly Black women killed in the first two weeks. While the Minister of Police stated that crimes overall had decreased during lockdown due to a ban on alcohol sales, with the prevailing idea being that the return to selling alcohol had fuelled the increase in femicides, women’s rights advocates were quick to point out that calls to women’s help centres surged by 54 per cent throughout lockdown, in all provinces. Shelters were overwhelmed. One victim during this time was Altecia Kortje, who reportedly sought a protection order against her husband but was told by police to wait until restrictions had lifted: a week later, she was murdered by him along with their daughter. President Cyril Ramaphosa mourned the surge in femicides in an address to the nation in June 2020 as a ‘second pandemic’, but neglected to mention the equally frequent killings of sexual minorities and gender non-conforming Black people.

After a nine-week lockdown was eased in South Africa, murders of women took a significant leap, with 21 mostly Black women killed in the first two weeks.

Lockdown in India: Migrants hit hardest by restrictions

The lack of consideration of how drastic measures carried out in the name of public health can prove devastating for already marginalized communities was perhaps most pronounced in India. No planning was put in place to mitigate the catastrophic results of the world’s largest lockdown for people with no access to social protection programmes. After a nationwide lockdown was suddenly announced on 24 March with no prior warning, millions of migrant workers, many of whom are from Dalit, Adivasi and other marginalized communities, had no other option but to march out of metropolises on foot after the rail system was shut down, with hundreds dying en route. The lockdown, imposed arbitrarily by the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi with little or no prior consultation, showed scant regard for the security and well-being of millions of migrant workers. Far from protecting public health, it only served to corral people together in masses as they tried desperately to escape the cities.

Most were daily wage labourers, with no savings or social safety nets, and so forced to return to their rural homes. Dalits have reported facing stigmatization upon return, both as outcasts and suspected carriers of the virus. Government work schemes and ration programmes have been criticized for not reaching the most vulnerable, but only benefiting higher castes. The lockdown was economically devastating for minorities: according to the COLLECT (Community-Led Local Entitlements and Claims Tracker) data initiative, increased debt was recorded among all of India’s minorities and indigenous peoples including Dalits, Muslims, Adivasis, and Nomadic and Denotified Tribes. Loss of livelihoods resulting in an increase in debt can lead to intergenerational forced and bonded labour.

Strikingly, as the situation in India rapidly deteriorated from March 2021, with a sharp spike in infections and deaths, many urban migrant workers again uprooted themselves from cities across the country to return to their villages. Fear of the rapid spread of the virus and the government’s ongoing failure to contain the unfolding tragedy drove these departures, despite the absence this time of a nationally imposed lockdown. Their exodus was undoubtedly inspired, too, by the trauma of their treatment a year before: in the words of Arundhati Roy, writing for The Guardian, ‘They’ve left because they know that even though they make up the engine of the economy in this huge country, when a crisis comes, in the eyes of this administration, they simply don’t exist.’

Insecurity in Colombia: Targeted violence on the rise

Most of the states that instituted nationwide lockdowns did not have prior experience of doing so, certainly not in the name of public health. The ways in which lockdowns — instituted with such urgency — would play out in existing conflict dynamics was not properly taken into account in many circumstances, leaving marginalized communities in the crossfire. In Mexico, for example, the lockdown was used by narco-traffickers and paramilitaries to expand territorial control at the expense of indigenous peoples, especially in the southern states of Chiapas and Oaxaca. ‘There is no pandemic for the paramilitaries’, explained Rubén Moreno, an indigenous rights activist from Chiapas in an interview with Equal Times. ‘Paramilitaries continue their violent actions, and indigenous people have no access to justice. This is absolute discrimination — and why does it exist? Because we are indigenous.’

In Colombia, the government-ordered lockdown made indigenous human rights defenders more vulnerable to targeted killings and assassinations. While even before the pandemic Colombia was already regarded as the deadliest place in the world for environmental rights defenders, many of whom are indigenous or Afro-Colombian, the numbers of those killed increased in 2020. According to Colombian NGO Indepaz, 113 indigenous rights defenders were killed, around 25 per cent more than in 2019. During the nationwide lockdown, indigenous leaders lost or faced reduced protections from state security, including bodyguards or night patrols, at a time when — forcibly confined to their homes and unable to move in response to threats — it was easy to locate and kill them without witnesses in a public setting. Furthermore, with state forces focused on Covid-19, armed paramilitaries were able to reinforce and strengthen their activities. As summarized to Amnesty International by Danelly Estupiñán, a human rights defender with the Process of Black Communities (PCN) in Buenaventura, Colombia:

‘Our enemies are still killing us and it’s not difficult for them during the pandemic because we are all at home, complying with the mandatory quarantine which means nobody can move. But it seems that the people who want to silence us are moving around without any problem. We are seeing a pattern whereby illegal armed groups come to social leaders’ homes and kill them in front of their families. In some cases, they kill their relatives as well.’

The lockdown had further ramifications on recruitment by non-state armed groups of children, many of whom are indigenous or Afro-Colombian, with more than double the number of minors recruited in the period of January to April 2020 than the total reported for the whole of 2019. The increase in child recruitment is thought to have come from lockdown school closures, which removed the protective spaces that were buffering children from recruitment while parents struggled with the socio-economic pressures brought on by the pandemic response.

Faced with this alarming situation, compounded by the economic fallout of Covid-19, indigenous leaders organized a march to the capital of Bogotá to stage a minga – meaning shared work or joint effort in indigenous Quechua – to protest the continued killings of leaders and the slow implementation of the 2016 Peace Accord with FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) rebels. The march began on 8 October 2020 in the south and south-west, convening first in Cali, then marching 600 kilometres to the capital, where thousands gathered on 19 October. Leaders demanded to be met by President Ivan Duque, who instead flew to Cartagena for a private event.

Despite the challenges of the pandemic and the threat of police violence against protests, indigenous activists have continued to mobilize during 2021, including holding large-scale demonstrations in the city of Cali in April. These actions are driven by a belief that without sustained action, the violence and abuses will simply continue. ‘Not even the pandemic will stop our movement’, said Hermes Pete, head of the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC), to Al Jazeera. ‘There is no other path but to keep fighting.’.

A community-led approach to containment: Māori checkpoints in New Zealand

Many governments, having delayed too long their response to the global spread of the virus, acted belatedly with knee-jerk, top-down responses that were not instituted through informed discussion with communities. It could be argued that governments did not have the experience or mechanisms in place to engage in rapid consultations to assess disproportionate impacts on vulnerable communities. But for indigenous peoples with established governance systems, there was a clear rationale for the response to be designed and initiated by indigenous communities, with the necessary funding in place to do so, in order to ensure effective and culturally appropriate action.

In New Zealand, Māori leaders realized that they must lead on the response to the virus in order to maximize the protection of their community. Māori swiftly organized themselves, with the support and operational presence of local police, to set up 40 community checkpoints across the country, strongly encouraging travellers not to continue into iwi (tribal) territory. Operating on a 24/7 basis, checkpoints offered safety advice for local essential workers who needed to pass.

According to community leader Tina Ngata, the checkpoints were a form of direct action that stemmed from their remembrance of how hard Māori were hit in previous epidemics, stemming back to the 1700s and waves of Western explorers. ‘It is easy to understand the unease Māori communities felt when Covid-19 arrived on our shores’, Ngata explained in the journal Overland. ‘When you further consider that not only has the state historically failed to protect our ancestors, but that the common Indigenous experience of colonization includes the use of disease as a genocidal weapon, then you can understand why we could not wait for anyone to come and save us.’

Their preventive action was met with criticism from right-leaning parties, questioning the legality of the checkpoints, claims which were refuted by the police. Community members, however, spoke warmly of the state-Māori collaboration, highlighting the positive engagement of police in the process — a welcome development in itself, given the long history of mistreatment and violence Māori have suffered from law enforcement.

According to Colombian NGO Indepaz, 113 indigenous rights defenders were killed in 2020, around 25 per cent more than in 2019.

Covid-19 and conflict: Escalating human rights abuses in Myanmar

Covid-19 added another layer of volatility to existing conflict situations, particularly for vulnerable communities fleeing violence, such as displaced persons, refugees and asylum-seekers. Some warring parties, however, appeared to treat it as an opportunity to tip the scales in their favour. On the very same day that the UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for a global ceasefire in order to focus on the fight against the spread of the virus, the Myanmar government made three announcements: Covid-19 was in Myanmar; the Arakanese Army (AA) was a terrorist organization; and websites spreading ‘fake news’ were to be shut down. All three announcements were to escalate the conflict in Rakhine state, complicate the response to the pandemic and highlight the Myanmar government’s disregard for the health and survival of its own people.

The AA is one of many of Myanmar’s armed ethnic organizations fighting for self-determination and political autonomy from the central government. While relatively newer than its counterparts, it has successfully countered the military, known as the Tatmadaw, in its home of Rakhine state at the expense of the local civilian populations who have faced reported atrocities from both sides. Declaring it a terrorist organization served the purpose of distinguishing it from other armed groups, criminalizing anyone who communicated with the AA, including journalists and humanitarian workers. Three journalists were arrested thereafter for interviewing the AA. This designation has prevented meaningful cooperation and coordination on a Covid-19 response. An internet shutdown in eight townships in Rakhine and Chin states, in part designed to create a stranglehold on AA communications since June 2019, combined with the shutdown of two key Rakhine state news organizations as designated ‘fake news’ outlets, meant that crucial information on Covid-19 was not reaching key populations. Conveniently, these two news organizations are those that are doing on-the-ground reporting of the conflict.

While the government heeded the call for a ceasefire on 9 May 2020 in relation to its numerous other conflicts, this did not apply to the AA. Conflict continued to rage in the state, with the numbers of those displaced doubling throughout 2020 to reach over 100,000. Covid-19 infections in Myanmar have been most numerous in Rakhine, with random testing in camps for displaced persons suggesting that community transmission is widespread – unsurprisingly, given the cramped and unsanitary conditions. The deadly effect of the conflict on the pandemic response was epitomized by the 20 April killing of a World Health Organization (WHO) driver who was delivering Covid-19 test results in a marked WHO van. Both the Tatmadaw and AA denied responsibility. In September, 70 people fled a quarantine centre in western Rakhine state after a night of nearby fighting. ‘We do want to stay at home but we can’t’, explained a villager sheltering at a monastery to The Irrawaddy newspaper. ‘Though we are afraid of coronavirus, we are also afraid that artillery shells might fall.’

Aid from the government in response to Covid-19 has been limited and poorly organized. At the very start of the pandemic, six Sittwe-based local civil society organizations established the Arakan Humanitarian Coordination Team (AHCT) to coordinate humanitarian assistance to those in Rakhine. They work both with the government and international donors to coordinate efforts, including for overlooked displaced populations who are not residing in established camps. They have also set up community quarantine centres and provided necessary supplies. Restrictions on movement have had serious consequences for aid and relief, with organizations required to secure official clearance to go to the camps to provide assistance, and with negative Covid-19 tests required just to drop off supplies. Even with permission, they are stopped at military checkpoints and, in October 2020, an authorized boat carrying supplies for the ICRC (International Committee of the Red Cross) was attacked by the Myanmar navy, killing the captain and damaging the vessel.

After elections in November saw a landslide win for the National League for Democracy (NLD), the military seized power on 1 February 2021 and used the Covid-19 crisis to justify, realize and solidify their rule. NLD chairperson and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi was arrested and charged with ‘breaching Covid-19 restrictions’ under a recently junta-altered section of the Penal Code. Anti-Covid measures have been used to justify swift and brutal crackdowns on the population. The military actively suppressed the responses of armed ethnic organizations to Covid-19 before it seized power, and it continues to be the primary impediment to an effective response in the country, despite presenting the pandemic as a pretext for its illegal actions.

Business as usual: Land grabbing and deforestation in Indonesia

The Covid-19 pandemic has given governments the opportunity to rush through controversial laws, policies and practices under the guise of economic recovery. According to a Forest Peoples Programme report covering countries with the largest remaining tracts of tropical forests – Brazil, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia and Peru – social and environmental safeguards were rolled back extensively in 2020. States are prioritizing expansion of mining and logging, infrastructure development, agro-business and the energy sector in or near indigenous territories with little regard for existing rights protections, enacting new land use regulations and corporate stimulus packages at the expense of existing consultation mechanisms. Similar trends have been recorded in Honduras, India and the Philippines. Urban inhabitants returning to rural areas in response to lockdowns further increased pressure on forests. As a result, according to data from Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) – a worldwide warning system for the depletion of tree cover that uses satellite data – global deforestation rates surged in 2020, increasing by 77 per cent compared to the previous three-year average.

In Indonesia, the first 20 weeks of 2020 saw a 50 per cent increase in loss of forests compared to the same period in 2019, according to GLAD. Despite this alarming situation, the Indonesian government decided to push forward legislation that will further erode indigenous rights to land and their crucial role in forest preservation. The Workplace Creation Law, referred to as the Omnibus Law, was passed by parliament in October 2020 and enacted by President Joko Widodo overnight on 3 November. It is essentially a neoliberal deregulation package, promoted as a means to streamline economic rejuvenation, that makes more than a thousand amendments to 79 laws, dissolving existing indigenous, local community and labour rights by removing environmental and social impact assessments; deregulating mining; reducing penalties for environmental violations; and excluding indigenous peoples from consultation processes. Massive street protests across Indonesia accompanied the bill’s passage, uniting the labour, student, indigenous and environmental movements, and resulting in thousands of arrests. Some were simply detained for online posts opposing the bill.

A coalition of Indonesian indigenous organizations submitted an urgent complaint to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), noting that: ‘Rather than respecting indigenous peoples’ rights and the advice of human rights experts, the Indonesian government has instead used the Covid-19 pandemic to rush through approval of the Law, hold discussions over the Law without notifying the public or consulting with affected rights holders, and vote on the Law without the required quorum of members of Parliament physically present.’

In Indonesia, the first 20 weeks of 2020 saw a 50 per cent increase in loss of forests compared to the same period in 2019.

Consolidating power: Turkey’s crackdown on dissent

Covid-19 has also been used as an opportunity to deflect attention from the actions of unpopular governments and bolster low approval ratings. In what was referred to as the ‘coronavirus polling bump’, many governments significantly increased their popularity in the first weeks of the pandemic, a common phenomenon during times of crisis. According to the Metropol Research Company, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s approval rating jumped from 41.9 per cent in February 2020 to 55.9 per cent in March, its highest point since the attempted coup in 2016. Riding high on this new-found approval, laws increasing government control over media, social media, academia and civil society were passed, as Erdoğan continued to consolidate power and weaken the opposition.

The pandemic emboldened Erdoğan’s attacks on the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP), as he continued to remove and arrest democratically elected HDP mayors, replacing them with hand-picked appointed trustees. While his campaign to remove HDP mayors began immediately after the elections in March 2019, in the first three months of the pandemic, trustees were appointed in 14 municipalities, primarily in the Kurdish south-east, and by the end of 2020, 48 out of 65 HDP mayors had been replaced, with 19 in pre-trial detention. This occurred despite the considerable disruption this entailed for a concerted pandemic response in these areas: after Turkey recorded its first Covid-19 case on 11 March, HDP mayors had played an active role in organizing relief efforts in their communities.

The south-eastern municipality of Batman, for example, had postponed water bills as a pandemic relief measure and was one of the first to have a trustee appointed. As 90 per cent of residents in Batman speak Kurdish, the HDP mayor had ensured that Kurdish-language versions were included in municipal settings, such as traffic signs. However, the appointed trustee immediately removed bilingual signage, leaving only Turkish. This lack of respect for minority language rights has also hampered an effective Covid-19 response. ‘Since the government has not provided services in our mother tongue’, a senior HDP representative told The National newspaper, ‘people cannot properly benefit from health services. All the posters and pamphlets on coronavirus precautions are prepared in Turkish and most people do not understand.’

As a response to lack of support from the central government, HDP initiated the ‘Sister Families campaign’ in March 2020 to encourage solidarity between families, pairing better-off households with those that were struggling economically to provide packages of basic necessities. Over 60,000 families were assisted by the programme. However, government-aligned media outlets described the campaign as ‘aiding a terrorist organization’. The government detained, and has filed lawsuits against, HDP representatives and volunteers who were implementing the campaign in many different cities.

In June 2020, two HDP deputies, Leyla Güven and Musa Farisoğulları, were stripped of their parliamentary seats and imprisoned on terrorism charges, accused of being members of banned militant Kurdish PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) organization. In response, HDP organized a two-track ‘Democracy March’, which was planned to start from both the north-western province of Edirne and the south-eastern province of Hakkari and converge in the capital, Ankara. Soon after, protests were banned in 12 cities by their respective governorships, ostensibly to limit the spread of coronavirus. Most of these bans were only for a couple of days, which would mostly stop the protests, not the spread of coronavirus. Despite the bans, protests were held in 11 provinces and were met with police use of force and detentions of protesters. In December, Leyla Güven was sentenced to 22 years in prison. As the pandemic continues, the government has persisted in its campaign to silence the HDP, with a state prosecutor filing a formal request in March 2021 for the party to be outlawed in its entirety – a move condemned by its supporters as a calculated blow to democracy in the country.

Public health as a pretext for anti-migrant policies: Title 42 in the United States

The pandemic resulted in an unprecedented shutdown of borders worldwide, impacting in particular those fleeing violence and seeking protection. By 1 April 2020, over 91 per cent of the world lived in states restricting all international arrivals, and 39 per cent in states with total border shutdowns for non-citizens and non-residents. Border militarization intensified in numerous states, accompanied by nationalist rhetoric that wove xenophobic language together with ‘battling’ against the coronavirus. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán blamed the spread of Covid-19 on illegal migrants and shut the country’s borders to asylum-seekers, while ignoring the significant occurrence of hospital-acquired infections spreading in under-funded, unprepared public hospitals. European Union border guard agency Frontex used the pandemic to justify its existence and consolidate its role, blurring migration prevention and public health protection: ‘If we cannot control the external borders, we cannot control the spread of pandemics in Europe. Frontex plays a key role in ensuring effective protection of the external borders of the European Union not only against cross-border crime but also against health threats.’

Minority and indigenous asylum-seekers in particular bore the brunt of worldwide border closure measures. In April 2020, the Malaysian air force denied entry to a boat carrying approximately 200 Rohingya refugees who had either fled from Myanmar or from camps in Bangladesh, citing concerns that they would bring the coronavirus into the country. Around the same time, the Bangladesh coast guard rescued boats with nearly 400 Rohingya on board: they had reportedly been turned away from Malaysia, with dozens dying as a result. Maritime expulsions were recorded in Malta and Italy as well.

Restrictive anti-immigrant and anti-refugee asylum procedures were a well-established cornerstone of US government policy throughout the administration of former US President Donald Trump. But the Covid-19 pandemic provided an opportunity to use public health law to expel up to 530,000 migrants and asylum-seekers and 16,000 unaccompanied children, an approach that would not have been possible under existing immigration law. On 20 March, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a sweeping order to instantly reject all those arriving at the border without adequate entry documentation, systematically denying the right to asylum. The CDC was reportedly pressured by the Trump administration to issue the order – known as Title 42 – despite resistance from senior CDC officials. Public health and medical experts opposed the order in a joint statement, saying it was not based on science-driven public health measures, but rather was an example of ‘xenophobic, cruel, and unlawful policies implemented by the Trump administration under the pretext of public health’. The order was renewed multiple times throughout the year, and after a review initiated by the Biden administration, has continued into 2021, with the exception of its applicability to unaccompanied children. While Biden officials claim that those who need it can still seek protection, in the year of Title 42’s application fewer than 1 per cent of arrivals were able to do so.

While US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) does not collect disaggregated data on race or indigeneity, civil society workers report that a large proportion of those seeking asylum in the United States (US) are indigenous or Black. Given that indigenous asylum-seekers as well as Black Haitian Creole speakers face significant language barriers and more frequent forced family separation, these figures are particularly disturbing. The ICE detention centre system became ‘a massive Covid-19 hotspot’, according to the Haitian Bridge Alliance, an NGO working with Black migrants. Deportations and expulsions that were occurring in 2020 have been blamed for spreading the virus to South American countries, and particularly to remote and indigenous communities that many of the forcibly returned asylum-seekers came from. By April, over half of those returned on flights to Guatemala who were tested on arrival were found to be infected. Indigenous Guatemalan deportees reported stigmatization, and in some cases violence, from other community members upon their return.

In the US, the pandemic provided an opportunity to use public health law to expel up to 530,000 migrants and asylum-seekers and 16,000 unaccompanied children, an approach that would not have been possible under existing immigration law.

Technology and surveillance: Tracking Singapore’s migrant population

Some of the big winners in the Covid-19 crisis have been tech companies specializing in data collection, monitoring and surveillance. Many of the companies that have honed their expertise in migrant and refugee tracking, border control and law enforcement have been repackaging the technology for pandemic surveillance and policing initiatives. Contact tracing proximity apps, facial recognition, drones and thermal cameras have been proposed by companies and governments alike to control the spread of the virus, blurring the lines that might normally prevent the use of military tech on civilian populations. Border control systems and tools were used during the crackdown on Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis on 25 May 2020, with drone surveillance being fed into Homeland Security Department digital networks used by other federal agencies, violating the privacy rights of people exercising their right to protest. In the weeks following Floyd’s murder, however, Microsoft and Amazon announced that they would not sell facial recognition technology to the police in the US until federal legislation was in place, while IBM said it would stop selling the technology altogether due to its use in racial profiling.

The development of contact tracing apps, however, has surged forward in response to the pandemic, and they are often adopted through fast-track legislative or executive power procedures. While they can be designed to protect users — for example, by not storing personal data or collecting geolocation data — many Covid-19 contact tracing apps developed thus far are insecure and risk exposing users’ privacy and data. Also, given that many surveillance technologies tend to have been built on racially biased algorithms or are employed in ways that disproportionately impact minority, indigenous and other marginalized communities, it is particularly concerning that the rapid rollout of various Covid-19 surveillance technologies has not been accompanied by significant efforts to mitigate this potential impact.

Out of the over 40 countries that initiated digital proximity and contact tracing tools, Singapore was one of the first with the digital system TraceTogether, offered as an optional measure for the country’s citizens but imposed mandatorily on Singapore’s Covid-wracked migrant worker population. Hailing mostly from India, Bangladesh and China, hundreds of thousands of migrants work primarily in the construction and shipyard industries and reside in cramped dormitories. In these crowded and unsanitary conditions, infections quickly spread among migrant workers, who were then subjected to a brutal lock-and-seal programme. Following the end of their isolation, TraceTogether was required in order for them to return to work. The app was later supplemented by a Bluetooth-enabled ‘token’ to be worn on the worker’s wrist, also available to members of the wider population who might not have a smartphone, such as children and the elderly. While privacy and migrant worker advocates were concerned about TraceTogether data usage, assurances were fatally undermined when a government official admitted in January 2021 that the data could be accessed by police and in fact had already been used in a murder case. These troubling implications are being reflected in other countries across the world: once instituded, mandatory use of tracking technology will invariably be difficult to roll back and could be used to justify over-policing of minorities.

Biosecurity and public health: Policing the pandemic in Australia

A central issue connecting the different examples discussed in this chapter is the increasing cohesion between policing and public health, a securitized approach that tends to target or unfairly disadvantage minorities, indigenous peoples and migrant communities. In Canada, for example, ‘Public health has historically been an extension of policing for Black people.’ This is illustrated by the case of Africville, Nova Scotia, a predominantly Black community existing since the 1800s which was forcibly evicted in the 1960s on the pretext of a health risk due to the lack of a sewage system, instead of the authorities simply installing sanitation. Similar trends have been identified in more recent patterns of police stops, fines, detentions and arrests of Black people in relation to Covid-19. Indeed, reports from throughout the Global North show that minorities have been disproportionately targeted in Covid-related policing.

In anticipation of the pandemic’s likely impact on policing of minority and indigenous communities in Australia, a coalition of legal and human rights advocacy networks in collaboration with academics created an online portal to report instances of Covid-related stops by the police. This serves as a mechanism with which to monitor expanded police powers under lockdown and assess whether they are being applied without bias or prejudice. The data collected by the portal paints a sobering picture: Covid-related police stops and fines disproportionately targeted individuals from indigenous or Black communities. In an article analysing the portal’s data, the authors argued that the results demonstrated that the state is choosing criminalization over a public health paradigm:

‘We found Covid policing to provide opportunities for the intensification of longstanding and selective criminalisation processes, evident in the disproportionate focus on First Nations peoples in street policing and the high-visibility policing of racialised and socio-economically disadvantaged communities in public housing.’

Using a biosecurity approach to public health essentially pits communities against virus prevention measures: rather than building solidarity and informed action in bottom-up participatory approaches, communities are disempowered and treated as complicit in the spread. Bullying by law enforcement in the name of public health has been shown to weaken adherence to preventive measures and undermine the trust that is essential in promoting compliance.

Out of the over 40 countries that initiated digital proximity and contact tracing tools, Singapore was one of the first with the digital system TraceTogether, offered as an optional measure for citizens but imposed mandatorily on migrant workers.

Art and activism in the wake of Covid-19: Imagining the post-pandemic future

The year 2020 was one of seismic changes across societies worldwide, triggered by the upheaval brought about both by the virus itself and the response by many governments ostensibly intended to address it. But the onset of the pandemic also converged with the murder of George Floyd, creating an urgent momentum to push racism and injustice to the forefront of activism across the world.

According to Marshall Shorts, founding member of Deliver Black Dreams Maroon Arts Group based in Columbus, Ohio, 2020 witnessed the convergence of multiple pandemics: a moment when people were forced to face questions of racism and violence which Black artists have been reckoning with for a long time. Maroon Arts Group is ensuring that these conversations around racism and inequality, particularly in the wake of Covid-19, continue to take place after the health crisis has passed, so that countries do not simply fall back into pre-pandemic patterns of racial disparity.

As the lockdown eased, the Greater Columbus Arts Council employed artists to paint murals on the plywood that was used to board up businesses during the demonstrations against Floyd’s death, as a way to bear witness to the protests but also provide a public platform against racism. As a follow-up to the project, Marshall’s group was commissioned to make a more permanent 5,000 square foot mural that says, ‘Deliver Black Dreams, It’s for All of Us’. Marshall says the mural has been used as a testament to the protests and to keep the conversation around race ongoing. He explains:

‘It’s a call to action… It is on all of us to Deliver Black Dreams, but it is also to say, we have to have a radical imagination of what this society can look like, and then take action toward that… What does Delivering Black Dreams look like in health care, education, safety?’

Conclusion

As we move towards a post-pandemic future, we must collectively remember how the pandemic has thrived on society’s structural inequalities and address these weaknesses so they cannot be exploited again. As vaccine rollout begins throughout the world, these same considerations on inequality need to be prioritized if we are to be able to collectively rise above these continuing challenges. If the remedies to the pandemic do not address structural discrimination, we will find ourselves struggling to move into a post-pandemic future. After all, ‘We are only as free of risk as the most vulnerable in society.’

The responses that have already been initiated by governments, as outlined in this chapter, may serve only to further facilitate the spread of the virus, entrenching discrimination, infringing rights and making it more difficult for civil society to resist these changes. The community resistance and collective organization that has also occurred during the pandemic leaves some hope that the ‘radical imagination’ of societies, premised on equality, will be realized as the world emerges from the trauma of Covid-19. Ensuring equity and human rights for all is the best means possible to strengthen our resilience in the face of further pandemics and other future shocks.

Recommendations

- Ensure a human rights-based approach to containing Covid-19: Struggles for rights protections are bound to increase as societal structures bear continuing impacts from the pandemic. Governments need to structure their wider response around rights protections, ensuring that any initiatives do not negatively impact on fundamental rights, such as the right to protest and the right to privacy. Emergency measures must not be used to silence dissent.

- Place communities front and centre of public health campaigns: Deep engagement and informed dialogues with communities are the best ways to increase effectiveness and compliance. Local innovations and inclusion are necessary to build collective responsibility and power.

- Enhance support for at-risk human rights defenders: Minority and indigenous rights defenders must be facilitated in their work supporting communities and responding to crisis. This includes journalists and other media workers who are trying to protect independent, non-biased reporting.

- Collect and publish disaggregated data on health outcomes: It is vital to know how minorities and indigenous peoples are specifically affected by the pandemic, as this will guide efforts to appropriately target assistance and treatment to the most vulnerable communities. To control the spread of the virus, it is necessary to understand how transmission is itself facilitated by discrimination.

- Recognize and address the intersectional impacts of the pandemic: Those suffering from discrimination on multiple and intersecting points of identity, such as gender, sexuality, age, ability and class, will be even more exposed during times of crisis. Overlooking their experiences in the midst of a pandemic not only jeopardizes the security of those most at risk, it also poses a threat to the rest of society.

- Ensure assistance is inclusive and equitable: Any responses to the pandemic, whether social support or vaccine rollout programmes, must recognize and mitigate the disproportionate impacts on the rights of minority and indigenous peoples. Furthermore, solutions must be found through engagement with the communities themselves.

- Challenge hate speech and misinformation: Governments and human rights bodies should publicly acknowledge the risks of discrimination enabling the spread of Covid-19 and take proactive action to protect minorities and indigenous peoples from hate, including through public education, incident monitoring and reporting.

Photo: Colombian indigenous people protest Colombia’s President Ivan Duque’s policies during an indigenous meeting called ‘Minga’ in Bogota, Colombia. Credit: REUTERS/Luisa Gonzalez.

-

By Rasha Al Saba and Samrawit Gougsa

Amid a global recession triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic, minorities and indigenous peoples have been hit especially hard in the world of work. Not only have members of these communities lost their sources of income, they have also been left vulnerable to work in unsafe and exploitative conditions.

This chapter explores the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on the livelihoods and incomes of minorities and indigenous peoples as the crisis has unfolded. In particular, it examines the limitations of the policies put in place by different governments to protect workers and their rights, the continued pattern of exploitation and abuses that minority and indigenous communities face in the labour market, and the way these issues overlap with deeper patterns of discrimination that pre-date the pandemic itself.*

Loss of jobs, income and livelihoods

Besides the direct effects on public health, a major consequence of the pandemic has been unemployment, with the International Labour Organization (ILO) reporting that 8.8 per cent of global working hours were lost in 2020 alone, equivalent to 255 million full-time jobs, resulting in an estimated US$3.7 trillion in lost income. While many jobs in the formal sector were protected through government schemes, the informal sector – where the majority (61 per cent) of the world’s workforce are engaged and where minorities and indigenous peoples are overwhelmingly represented – has been much worse affected. The very nature of the informal economy means workers do not have secure employment contracts, access to labour protections or social protection through their employment, leaving them more vulnerable to exploitation and financial instability. Moreover, the gendered nature of this should be noted, as over 90 per cent of women in low-income countries are employed informally, leading to an even more profound impact on them.

Migrant workers on the margins of the global economy

Migrant workers across the world are often employed informally and have been severely affected by Covid-19. Not only have many lost their jobs, but some have even been physically abandoned by their employers to fend for themselves. In Lebanon, for example, where the economy was already in crisis even before the pandemic, scores of predominantly Ethiopian migrant domestic workers were fired and left on the street outside their country’s consulate in the capital city, Beirut. Most of the women had little or no money and relied heavily on the support of non-government organizations (NGOs) as they waited to be repatriated.

The Covid-19 pandemic also placed a spotlight on the vital contributions of migrant workers in the agricultural sector in maintaining food supplies locally and internationally. Countries that rely heavily on foreign workers in this sector saw significant labour shortages, not necessarily due to Covid-19 itself, but instead the measures put in place by governments to restrict the spread of the virus, particularly travel and containment rules. For example, in Canada, every year farmers rely on an estimated 60,000 foreign workers, mainly from Mexico, Guatemala and Jamaica, to harvest their crops. In the early months of the pandemic, however, Ontario was the epicentre of the country’s Covid-19 outbreak, where more than 1,000 migrant farm workers tested positive. As a result, many employers enforced strict rules, in particular on the foreign workers, whose visas are attached to the farmers they work for, resulting in a power imbalance where workers could easily be sent back to their home countries. Indeed, many were dismissed after accusations by employers of not following their imposed restrictions.

Migrant workers in India, most of whom are from Dalit and Adivasi backgrounds, also faced difficulties. Following lockdown, tens of millions of migrant workers lost their work in urban areas and were forced to return home, often to rural villages, without any clear means of survival. Yet the situation facing Dalits and Adivasis in South Asia expands beyond India. In Nepal, for example, a survey by the Samata Foundation of 1,500 Dalit respondents found that over 80 per cent reported financial distress due to Covid-19 and the restrictions introduced to contain its spread, with 45 per cent having lost their jobs in the wake of the pandemic. The fact that the large majority of Dalits are daily wage workers makes them especially vulnerable to the economic crisis brought on by the pandemic, leaving them struggling to make ends meet. The impact of unemployment and reduced incomes on migrant workers is also felt by family members in their home regions who rely on remittances – a particularly significant issue in South Asia, where a major share of global remittances are channelled by migrant workers elsewhere in Asia, the Middle East, Europe and North America.

The pandemic has also heavily affected global garment supply chains, where minorities and indigenous peoples are often employed, as demand for clothing and apparel dramatically reduced. Many retailers were quick to cancel or postpone production orders which, in many cases, had already been fulfilled ahead of delivery. For example, according to the Bangladeshi Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, by April 2020 more than 1 million Bangladeshi garment workers had been sent home without pay or lost their jobs after Western clothing brands such as Primark and Matalan cancelled or suspended £2.4 billion of existing orders in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

In many cases, the companies refused to pay for clothing that manufacturers had already produced, resulting in the closure of thousands of factories and millions of garment factory workers being left jobless, often without wages owed or severance pay. This exemplifies a clear power imbalance in the fashion and garment industry, whereby the upfront investment of labour is placed on workers in poorer economies who also take on the greatest burden of financial loss and risk. Moreover, such incidents are having a significant impact on the nutritional status of garment workers, as noted by a November 2020 global survey by the Worker Rights Consortium of garment workers in nine countries: 80 per cent of respondents with children reported that they were having to go hungry to feed their children.

In Nepal, a survey by the Samata Foundation of 1,500 Dalit respondents found that over 80 per cent were financially distressed due to Covid-19.

Indigenous livelihoods threatened as tourism slides

Like migrant workers, indigenous peoples are also disproportionately represented in the informal economy. As they often work in sectors heavily hit by the pandemic, particularly as a result of government measures to prevent the spread of the virus, they have experienced a severe impact on their livelihoods and traditional economies. One area that has been especially hard hit is the tourism sector as a result of lockdowns and travel restrictions. While at its worst the sector has been associated with exploitation and environmental degradation, it can also be a vital source of income and employment for many indigenous communities.

For example, due to the intimate knowledge of the land on which they have lived for centuries, the Khomani San of the Kalahari in South Africa offer hunting packages on their land around the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park on a commercial basis, to make a living. However, once lockdowns were enforced and tourism ceased, demand for their services drastically diminished, in turn reducing their income and leaving the community facing starvation. Moreover, as is often the case with hunter-gatherer communities who have been dispossessed of their ancestral lands, some were charged with poaching when they entered the park to hunt for food for survival during lockdown.

Similarly, in Colombia and Venezuela, women from the Wayuu community of Alta Guajira depended heavily on tourism for their income. According to a report by the Continental Network of Indigenous Women of the Americas (CNIWA) published in May 2020, the shrinking tourism industry led to approximately 50 children facing a critical state of malnutrition due to lack of food and water. This example highlights the severe impact that income losses for women can have on indigenous communities more widely.

Yet in some cases indigenous businesses have proved to be more resilient to the economic shock posed by the disruption in tourism. In the United States (US), for example, a survey conducted by the Native Hawaiian Chambers of Commerce and the Office of Hawaiian Affairs found that only 25 per cent of Native Hawaiian businesses reported their business to be over 50 per cent dependent on the tourism sector. In comparison, an estimated 47 per cent of non-Hawaiian businesses reported their revenue to be over 50 per cent dependent on the industry. The findings suggest that although Native Hawaiian businesses were also affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, they will play a crucial role in the economic recovery of the island.

Though tourism is an important source of income for minority and indigenous communities, the disruptions to the sector caused by Covid-19 highlight the precarity of depending on this form of income generation. The Pacific Islands, for example, successfully managed to keep the number of Covid-19 infections low during the first year of the pandemic but have been unable to escape economic hardship due to the decrease in tourism. Unlike their neighbours, Australia and New Zealand, the smaller Pacific Island countries often rely on aid and remittances and are not in a position to roll out robust stimulus packages. One key lesson of the Covid-19 pandemic is to consider how to remedy this dependence on tourism for minority and indigenous communities across the world, so that their income is more resilient to such shocks.

Exploitation and forced labour

Exploitation and forced labour – defined by the ILO Forced Labour Convention (1930) (No. 29) as ‘all work or service which is exacted from any person under the threat of a penalty and for which the person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily’ – thrive on desperation and inequality, leaving minorities and indigenous peoples especially susceptible. While forced labour existed long before the pandemic, the rise in global unemployment since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic has created an enabling environment for further abuses.

The use of forced Uyghur labour in PPE supply chains

Some sectors have seen a boom of business and supply that has matched an increasing trend of exploitation of workers belonging to minorities and indigenous communities. A clear example of this is the immense global demand for personal protective equipment (PPE), such as N95 face masks and medical gloves, with values increasing more than tenfold by early April 2020, according to the Society for Healthcare Organization Procurement Professionals. As various governments and businesses sought to produce PPE to match demand, reports began to emerge of abusive working conditions and human rights violations of minorities and indigenous peoples involved in the production of these goods. In China, for example, a New York Times investigation revealed that several companies were implicated in the exploitation of Uyghurs, a persecuted and largely Muslim ethnic minority, to produce medical masks in conditions of forced labour. Though the forced labour was being used by companies, the companies have been operating through a government-sponsored programme that many claim forces people to work against their will.

Slavery-like conditions in the Gulf

The Gulf states host the majority of an estimated 23 million migrant workers living in the Arab states. Though they are some of the richest countries in the world, with economies highly dependent on foreign labour, systematic abuse and exploitation of migrant workers has been well documented. Most notoriously, many migrant workers are subject to the ‘kafala’ system, which gives employers immense power and control over the lives of those on their payroll. Workers typically require the permission of their employers to change jobs and are often reliant on them for food, accommodation and legal documentation. Violations of migrant workers’ rights in the region include a lack of adequate health care; inhumane living conditions, including lack of adequate food and housing; and visa deprivation and non-payment of wages – situations that are indications of modern slavery.

The pandemic has caused a sharp increase in the abuse and exploitation of migrant workers in the Gulf, with the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre documenting a 275 per cent increase in reported labour abuses against migrant workers in Gulf countries between April and August 2020 alone. In 95 per cent of incidents, the victims cited Covid-19 as a ‘key or worsening factor’, while the most frequently cited abuse (81 per cent of all cases) was non-payment of wages. For those affected, challenging employers to recover unpaid wages has been especially difficult due to the extensive repatriation programmes carried out, often forcibly, on foreign workers.

In Saudi Arabia, a report by Equidem revealed that thousands of low-wage migrant workers employed by subcontractors for Saudi Aramco, the oil and gas conglomerate, were left unpaid for as long as six months during the Covid-19 pandemic. In the United Arab Emirates (UAE) too, thousands of construction workers employed on the Dubai Expo mega-project were dismissed without warning. Many of these workers, still owed unpaid wages, were returned to their home countries or forced to stay in poorly maintained accommodation.

Crowded together in unsanitary conditions and with limited access to health care, Covid-19 spread quickly among the Gulf’s migrant populations, triggering a wave of deportations and detentions, often in inhumane conditions. In Saudi Arabia, for example, Human Rights Watch reported in December 2020 that conditions in a deportation centre in Riyadh holding hundreds of mostly Ethiopian migrant workers were ‘so degrading that they amount to ill-treatment’. Detainees described unhygienic and overcrowded living conditions that made any kind of social distancing to prevent the spread of Covid-19 impossible; beatings were common, with at least three reports of deaths in detention.

In Qatar, meanwhile, some 2 million migrant workers make up about 95 per cent of the total labour force, sustained by the vast construction boom over the last decade ahead of the 2022 Fifa World Cup. Long before the pandemic, long working hours and limited labour protections were exacting a heavy toll on migrant workers: analysis published by The Guardian in February 2021 revealed that more than 6,500 migrants had died in the country since 2010, with little evidence of substantive investigations into the cause of many deaths. After hundreds of construction workers tested positive for Covid-19 at the start of the pandemic, Qatari police sealed off the country’s largest labour camp, leaving thousands of workers trapped in unsanitary and overcrowded living conditions that contributed to the high levels of infection among migrants.