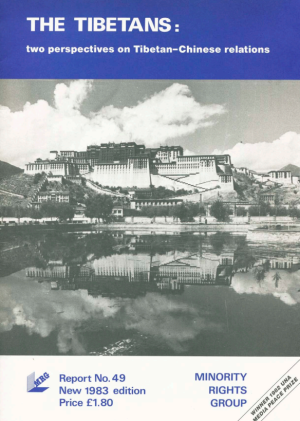

The Tibetans: Two Perspectives on Tibetan-Chinese Relations

The minority peoples of China divide into 54 nationalities and altogether constitute just 6 per cent of the population. In most other countries they would be considered statistically insignificant In China 6 per cent of the population is 54 million people. More importantly, they occupy over half the land area of China, much of it strategically vital.

Most Chinese – known as Han – are rice and wheat farmers who live crowded into the valleys of the Yangtse and Yellow rivers or in the fertile eastern coastal provinces. By contrast the minority peoples, some of whom do not concede that they are part of China, for the most part occupy the great grasslands, deserts and mountain regions in the extreme north, south and west of China. In some regions they straddle the borders with countries whose relationship with China is either hostile or cool – the Soviet Union, Vietnam and India.

Although nominally the minority nationalities have been part of the Chinese empire for many centuries, effective central government control over minority areas was exercised only by the strongest dynasties before the victory of the Communist Revolution in 1949. This has meant that in the past, provided that they posed no threat to the central government, the minority peoples were generally left in peace. Over the centuries, many of them developed unique and sophisticated cultures that survived and were undisturbed until the coming of the Chinese communists. From the beginning the communists professed a desire to preserve and even encourage the more benign aspects of minority cultures while at the same time enabling the minority peoples to contribute to and share in the development of China as a whole. In practice, this has not always worked out as planned. While there have been undeniable improvements in the health, education and even prosperity of many minority peoples in China, the promise of self-government has proved largely illusory. What has been presented as an opportunity for education and economic development has often turned out to be little more than an attempt to assimilate minority peoples into the Han culture. Religion, language and local agricultural practice has often been suppressed at the cost of great resentment and, in the case of Tibet, armed rebellion. The Chinese government now acknowledges that serious mistakes have been made in its treatment of minority peoples.

At the time of writing, a genuine effort appears to be underway to put right the wrongs of the past. For the first time in 15 years the practice of religion is again permitted; local languages and literature are being revived; Han officials in minority regions are now being replaced by locals. Inevitably, however, a question mark hangs over these latest changes. How long will they last? Will the line change again? Will there be another Great Leap Forward, another Cultural Revolution or another Gang of Four? Nobody knows. Whatever the answer, one other point must be made. The Chinese communists’ treatment of minority peoples in China has, for all its faults, been incomparably more civilized than that meted out by, for example, white settlers to the American Indians, the Australian Aborigines, the Indians in Brazil or for that matter the Palestinians in Israel.

This report looks first at the theoretical basis for relations between the Chinese government and the minority peoples of China. It then goes on briefly to compare theory with practice in China’s largest and most difficult autonomous region, Tibet. In a way it is unfair to concentrate on Tibet because it has been without doubt the least successful example of relations between the Chinese communists and a minority people. On the other hand; it does encapsulate everything that has gone wrong with the Chinese government’s policy towards minorities. Tibet offers another advantage.

More information is available on the subject than on any other of China’s minority regions. This is not saying a great deal. The minority peoples of China dwell in some of the most remote and inhospitable territories of the earth. They have been visited by very few outsiders, either before or since the revolution in China. Much of what has been written is based either on hearsay or interpretation of official publications or broadcasts. Tibet is different. Because its civilization seems to exert a unique fascination on the handful of westerners who have ever reached Tibet, many of them have written copiously about it. Besides which, because Chinese policy there went so badly wrong, 100,000 Tibetans now live in the outside world and have provided a steady stream of information (not all reliable) to anyone who cares to listen. Finally, the Chinese themselves, deeply embarrassed by their failure, have also fed the outside world with a steady flow of information (not all reliable) on Tibet. The result is that we know more about Tibetans than about any other of China’s minority peoples.

Please note that the terminology in the fields of minority rights and indigenous peoples’ rights has changed over time. MRG strives to reflect these changes as well as respect the right to self-identification on the part of minorities and indigenous peoples. At the same time, after over 50 years’ work, we know that our archive is of considerable interest to activists and researchers. Therefore, we make available as much of our back catalogue as possible, while being aware that the language used may not reflect current thinking on these issues.