Dominican Republic

-

Main languages: Spanish (official) and French/Creole (Haitians).

Main religions: According to recent surveys (Statista, Latinobarometro), around half of the population identify as Roman Catholic (centred on the veneration of the Virgin of Altagracia), with around one fifth identifying as Evangelical and one-fifth identifying as ‘No religion’.

Other religions include Adventists, Jehovah Witnesses, Bahá’i, Judaism and Islam. A relatively small percentage of the population follow Dominican Vudú, a syncretistic African spirituality developed by Africans and Afro-descendants, with a smaller percentage following indigenous spirituality (Taíno), based on ancestral practices centred on the worship of cemis.

Main minority groups and indigenous peoples: The majority of the Dominican population have mixed ancestry, with the vast majority of individuals being of Taíno indigenous descent, European descent (especially Hispanic) and/or African descent. According to a United Nations Population Fund study conducted in 2019, 45 per cent identify as being of indigenous descent, 18 per cent identify as white, 16 per cent identify as moreno (mixed indigenous and white); 9 per cent describe themselves as mulatto (mixed indigenous and black); and 8 per cent describe themselves as black (mostly Haitian descent). Asian communities have also settled in the country, including Japanese, Chinese and Indian, who in total represent less than 1 per cent of the national population.

The indigenous languages once spoken in what is now the Dominican Republic were diverse. People referred to as Taíno or ‘Indios’ by colonizers included a diversity of indigenous ethnic and linguistic groups including Igneris, Xiguayos, Macorixes, Kalibi or Kalinagos and Lucayos.

The generic name for the indigenous peoples of Dominican Republic and Haiti is Quisqueyano, although the term is also used to refer to Dominicans in general. The term comes from the indigenous name of the island, which is Kiskeya (Quisqueya in Spanish). In Taíno language, Kiskeya means ‘Mother of all Lands’.

Haitians form a distinct cultural and linguistic group within the Dominican Republic. Most Haitians are concentrated in the western regions of Dominican Republic, closer to the Haiti border. Haitians, Dominicans of Haitian descent and Dominico-Haitians have had a major influence in Dominican history and culture. Haiti was the first country in the Americas to gain independence (from France) through a slave revolt. Haiti is also the first country to abolish slavery in the Americas. These historical events greatly influenced the movement for independence in Dominican Republic and across the continent. Notable Dominicans of Haitian descent include former President Ulises Heureaux and numerous sportspeople, artists and human rights defenders.

-

The Dominican Republic is heir to the Spanish caste system and a legacy of colonialism and racial division that still characterizes Dominican society today. The colonial history of the Dominican Republic and neighbouring Haiti, as well as the protracted and brutal campaign against Taíno people, Africans and Afro-descendants, has contributed to the creation of exclusionary notions of ‘dominicidad’ that have privileged European and North American culture and ancestry over indigenous and African heritages and influences.

The Taíno indigenous population was decimated by Spanish colonizers through mass killings, forced labour and foreign diseases that affected Taíno communities during the 15th and 16th centuries, although some studies point out that the decline of indigenous populations and culture in the Dominican Republic occurred also due to infanticide and suicide carried out by local indigenous people to avoid sexual abuse, slavery, forced labour and forced conversion.

Taíno people were declared ‘extinct’ shortly after 1566, when a local census maintained that only 200 indigenous people remained in the island of Hispaniola (the Dominican Republic and Haiti). Since then, subsequent censuses have reiterated the historical claim that there are no indigenous people left in the island, a claim vehemently disputed by survivors of the Taíno genocide.

Many people in this country continue to self-identify as ‘indigenous’, and still follow Taíno ancestral ways of life. The rediscovery, revival or memory of indigenous Taíno culture is promoted in the Dominican Republic through the preservation of Taíno settlements, cultural centres, places of worship and the celebration of numerous traditional festivals. Taíno heritage also survives in myriad popular cultural forms, through culinary practices, farming and fishing practices, place names, architecture and spirituality among others.

Great controversy has surrounded the Taíno heritage of the Dominican Republic, as the narrative of extermination has led to the invisibilization and nullification of indigenous people and their rights. Taíno history has been eliminated from educational textbooks and national curriculum, while dominant scholarship continues to argue that Taíno people are extinct. Indigenous Taíno people claim that their culture and ancestral practices survive to this day due to intermarriage with other indigenous groups.

The Constitution of 2015 does not recognise Taíno in any of its articles, and no mention to indigenous rights to land, water or culture is provided by this framework. The national Census of November 2022 was the first time in the history of this country that the category ‘indio/india’ was offered as an official form of self-identification, although there is no reference to Taíno in the 2022 census form.

While indigenous people have been nullified by the narrative of extermination, black and Afro-descendent groups are visible in Dominican society, yet they face a different set of issues including marginalization, discrimination, economic deprivation, racism, hate speech, lack of basic rights and statelessness.

Haitians represent a significant minority of up to one million people within the Dominican Republic and form a distinct cultural and linguistic group. Many Haitians in Dominican Republic speak French/Creole, which is an unofficial language, not recognised in the 2015 Constitution.

Although many Dominicans have Haitian ancestors and connections, anti-Haitian xenophobia is rife. This is partly a legacy of the two countries’ troubled history and a reflection of Haitians’ low economic status. This population includes hundreds of thousands of Dominico-Haitians, born in the country and in many cases resident for generations, who have valid claims to Dominican citizenship as well as hundreds of thousands of Haitian immigrants, both documented and undocumented.

Many Haitians are employed, frequently in exploitative conditions, as cheap labour in Dominican sugar plantations and other poorly paid sectors. Widespread poverty and abject living conditions have been exacerbated by social stigmatization and official crackdowns.

Many Dominico-Haitians have faced bureaucratic hurdles to accessing documentation, despite valid claims to citizenship – a situation that only worsened with the Dominican Constitutional Court’s judgment TC/0168/13 in September 2013, which retroactively stripped hundreds of thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent of their Dominican nationality. While Dominican authorities subsequently issued Naturalization Law No. 169-14 in 2014 to address the situation created by the ruling, in practice many Dominico-Haitians have yet to have their citizenship approved. As a result, the country hosts a sizeable stateless population that, according to UNHCR estimates, exceeds 200,0000 individuals.

In the meantime, an official campaign of mass deportations has seen thousands deported to Haiti, including not only Haitian immigrants but also Dominico-Haitians with valid claims to citizenship who have never lived outside the Dominican Republic. The latter are now trapped in Haiti, a country many have never even visited, with limited means of securing a path to Dominican citizenship. While the Dominican government implemented a temporary 18-month moratorium on deportations in December 2013 to allow foreign undocumented migrants to regularize their status, mass deportations resumed in June 2015. Since then, tens of thousands of Haitians have been forced to return, with more than 4,000 Haitians deported and another 5,000 denied entry from Haiti in September 2017 alone. This official crackdown has been accompanied by widespread popular xenophobia and outbreaks of anti-Haitian violence by vigilantes that has encouraged many other Haitians to leave the country.

Few government officials acknowledge the existence of prejudice against Haitians and Taíno people. Officials, government representatives and mainstream media regularly and publicly assert that there is no discrimination against Haitians or other persons of dark complexion. Media representation of Haitians and Taíno people often convey stereotypical ideas, discriminatory views and prejudices that perpetuate what many critics would argue is a structural form of racism, and internalised colonial mindset in Dominican society, which is prevalent across social groups, including class and professional status. These forms of discrimination are furthermore intersectional, and they affect not only ethnic and linguistic minorities and indigenous people, but also, specific members of these communities, especially children, women, people with disabilities and members of the LGBTQI+ community in the Dominican Republic.

-

Environment

The Dominican Republic comprises the eastern two-thirds of the island of Hispaniola, which it shares with Haiti. It is bounded on the north by the Atlantic Ocean; on the east by the Mona Passage, which separates it from Puerto Rico; on the south by the Caribbean Sea. On the west it shares a 360 km frontier with Haiti. It has a total land area of 48,734 sq km.

The island is rich in biodiversity and a hotspot for endemic species that can only be found in this unique tropical island habitat. Species such as gavilán de la Hispaniola, Rosa de Bayahibe, cua, Ricord iguana, ebony and guayacán are some examples of the 325 species of animals and plants endemic and native to Dominican Republic.

According to the Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, the majority of these species are listed as under threat of extinction and could disappear in the next decade due to environmental issues such as global warming and climate change. Further environmental issues include the impacts of industrial farming and mass-scale tourism, which have led to river pollution, landfills, ocean and beach pollution, and plastic waste pollution.

In recent years, the issue of wildfires and deforestation in the mountainous border regions of western Dominican Republic has been aggravated by population increase. The deterioration of soils and water systems, and the serious levels of deforestation are often used by media and official bodies to stigmatize and stereotype Haitians, who are often blamed for environmental problems including overuse of natural resources.

History

Pre-Colombian

The original inhabitants of the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti/Dominican Republic) were the indigenous Taíno, an Arawak-speaking people who began arriving by canoe from Belize and the Yucatan peninsula between 6000 and 4000 BCE. Hispaniola is now recognized as the main cultural centre of the Taíno-Arawak, who also colonized most of the Caribbean islands in conjunction with indigenous people who sailed up from the Orinoco/Amazon region of South America.

Along with Ay-ti, another of the original indigenous names for the island was Quisqueya (or Kiskeya). It was renamed La Isla Española (The Spanish Island) by Christopher Columbus when he first arrived in 1492. This later evolved into the name Hispaniola.

Early colonial

At the time of the Spanish arrival an estimated 1 million Taínos lived on the island. Spanish attempts to use enslaved Taínos in gold mining after 1501 did not prove profitable. There was continued resistance and the Taíno-Arawak who were not killed disappeared into the inaccessible mountains.

Taíno-Arawak communities under the leadership of warrior chief Enriquillo carried out hit-and-run raids against the Spanish until 1534, when a peace treaty was signed. Over the following centuries the remaining indigenous Taíno-Arawak increasingly became intermixed with the African and European colonial populations. Although the official narrative is that Taíno ceased to exist as a distinct population, many Taíno indigenous communities survive in Dominican Republic and claim inter-marriage with other indigenous ethnic groups.

African diaspora

African slaves began arriving on Hispaniola in 1503, and in 1510 the first sizeable shipment, comprising 250 Black Ladinos, landed from Spain. Sugar cane was introduced from the Canary Islands, and the first sugar mill in the New World was established on Hispaniola in 1516. This led to a sharp increase in the importation of African slaves.

The first major slave revolt in the Americas occurred in Spain’s colony on Hispaniola (Santo Domingo) in 1522, when enslaved West Africans (Muslim Wolof) led an uprising. Many of the insurgents escaped to the mountains and formed the first independent African Maroon community in the Americas.

Sugar cane boosted Hispaniola’s economic growth but increasing numbers of imported Africans kept escaping into the island’s interior, linking up with residual pockets of indigenous Taíno-Arawaks. By the 1530s, escaped Maroon groups had become so pervasive that large armed escorts were required for travel outside the plantations.

Spanish interest in Hispaniola declined with the discovery of precious metals in South America, and new imports of enslaved Africans ceased. The colony sank into poverty and in 1697 Spain ceded the western end of the island, which became known as Saint-Domingue, now Haiti, to France.

On the eastern, Spanish side, called Santo Domingo, Spanish colonists, Euro-indigenous mestizos and free as well as enslaved Africans lived in a relatively flexible cattle-ranching environment where class and caste distinctions were more relaxed. This resulted in a population of predominantly mixed Spanish and African descent.

After 1700, the population of Santo Domingo was bolstered by additional emigration from the Canary Islands. The northern part of the colony was resettled, tobacco was planted in the Cibao Valley and the importation of enslaved Africans renewed.

The population of the Spanish colony grew and by 1777 it was estimated to be around 400,000, with a large proportion being of mixed background: it was calculated as Europeans (100,000), Africans (70,000) European/indigenous mestizos (100,000) African/indigenous mestizos (60,000), African/European mestizos (mulattos) (70,000).

Compared to the French forced labour plantation colony on the western side of the island, which had become the wealthiest in the New World, the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo remained poor.

Haitian Revolution

With the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution in 1791, the rich urban families associated with the Spanish colonial bureaucracy fled the island, while most of the rural hateros (cattle ranchers) chose to remain.

In 1801, Haitian revolutionary leader Toussaint L’Ouverture arrived in the eastern side of the island and proclaimed the abolition of slavery in Santo Domingo. Soon after Napoleon dispatched an army to subdue the rebellion and reintroduce slavery, but these forces were overwhelmed by Haitian revolutionary forces.

Even after the French defeat, a small army contingent remained in control on the Spanish side of the island. Slavery was re-established and many Spanish colonists returned. The French held on to the eastern part of the island for nearly two decades more, until they were expelled by the Spanish-speaking inhabitants, many of whom were cattle ranchers.

In November 1821 the Spanish lieutenant governor proclaimed Santo Domingo’s new status as the independent state of Spanish Haiti (Haiti Español). Nine weeks later Haitian forces, led by Jean-Pierre Boyer, entered and united both sides of island.

Spanish Haiti

The 22-year Haitian occupation definitively ended slavery in the eastern part of Hispaniola. However, unification also brought imposition of compulsory military service, restrictions in the use of the Spanish language and large-scale land expropriations.

Spanish colonial landowners – who as Europeans were forbidden to own property under the Haitian Constitution – were forcibly relieved of their holdings. Most emigrated to Cuba, Puerto Rico or Gran Colombia. Furthermore, the Haitian regime associated the Roman Catholic Church with the French slave-owning class and confiscated all Church property, deported all foreign clergy and made the remaining Dominican clergy sever ties with the Vatican.

In an effort to prove that Haiti could be the equal of any other nation and with France demanding reparations for the loss of their plantations before granting diplomatic recognition, Boyer introduced the compulsory production of export crops. However, Afro-Dominicans who had just won their freedom resented being forced to grow cash crops under Boyer’s Code Rural.

Furthermore, the elimination of some local customs like cockfighting in conjunction with the other reforms contributed to the tendency of Dominicans to see themselves as culturally different from Haitians in language, ethnicity, race, religion and customs.

The payment of reparations to France by Haiti crippled the Haitian economy; consequently, Haiti imposed heavy taxes on the Spanish-speaking part of the island. Furthermore, a diminished national treasury made it difficult to maintain troops on the eastern side. This made it easier for Dominicans to declare independence from Haiti, on 27 February 1844.

Independence

The first President of the independent state was Pedro Santana, a powerful cattle rancher, who served for three terms between 1844 and 1861. The fact that between 1844 and 1856 Haiti launched five unsuccessful invasions to re-conquer the eastern part of the island prompted the clergy and the wealthy elite to seek protection from foreign powers.

In March 1861, Santana gave the Dominican Republic back to Spain. However, the return was short lived. Spanish discrimination against the African/European mulatto majority population, coupled with restricted trade and other reforms, led to rising resentment.

In 1863, this pro-Spanish movement prompted a national war of ‘restoration’. Fearing a Spanish re-imposition of slavery on the eastern side of the island, Haitian President Fabre Geffrard provided the Dominican rebels with arms, sanctuary and a detachment of the best military fighters. The guerrillas triumphed and the country regained its independence in March 1865.

From 1865 to 1879, there were 21 changes of government and at least 50 military uprisings. In the south, the economy was dominated by cattle-ranchers and mahogany exporters while in the Cibao Valley, on the nation’s richest farmland, smallholder peasants grew subsistence crops supplemented by tobacco grown for export, mainly to Germany.

Out of the national turmoil emerged Gregorio Luperón, the dark-skinned mestizo leader of the tobacco farmers who assumed the presidency. He enacted a new Constitution that set a two-year presidential term limit and a system of direct elections.

Sugar industry

After 1879, Cuban sugar planters moved to the Dominican Republic to escape the turmoil of the anti-colonial war on their island. The Cubans settled in the south-eastern coastal plain, and, with assistance from Luperón’s government, built the nation’s first mechanized sugar mills. Italian immigrants, Puerto Ricans (of German origin) and Americans later joined them. Together they created the Dominican sugar bourgeoisie and under their management the Dominican Republic became a major sugar exporter.

Caribbean workers

An 1884 slump in sugar prices led to a labour shortage. The gap was filled by English-speaking Afro-Caribbean migrant workers (cocolos) from the Virgin Islands, St Kitts and Nevis, and Antigua. They were often the victims of racism and xenophobia but many remained in the country. By 1897 sugar had surpassed tobacco as the leading export and some 500 kms of private railway had been built to service the sugar plantations.

General Ulises Heureaux

The emerging sugar interests found an ally in the person of General Ulises Heureaux when he came to power in 1882. Given the attitudes to ‘blackness’ in Dominican society it is significant that Ulises Heureaux was born of a Haitian father and a mother from St Thomas (Virgin Islands).

For over two decades Heureaux brought unprecedented stability to the Dominican Republic. The Heureaux government helped set up sugar mills, developed the army and undertook a number of modernizing projects, including the electrification of the capital, and introduction of telephone and telegraph services and other infrastructure and communication improvements. He borrowed heavily from European and US banks to achieve this national modernization effort.

When sugar prices plunged sharply in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, the government was unable to repay its foreign loans. In 1899, Heureaux was assassinated by disgruntled tobacco merchants. He left a large national debt.

US intervention

Dominican foreign debt provoked some European nations to threaten gunboat intervention. In 1906, alarmed at the increasing European influence in the region, the Roosevelt administration in the United States assumed responsibility for the Dominican Republic’s debt and took control of the country’s administration and customs management under a 50-year treaty.

In November 1916, after a decade of internal disorder, a coup d’état by the then Minister of War Desiderio Arias provided the pretext for US Marines to invade and establish their own military government. As in neighbouring Haiti, the US reorganized the tax system, expanded primary education and built new infrastructure.

Conflict arose in the 1920, when US authorities enacted a Land Registration Act that dispossessed thousands of Dominican peasants in the south-west, near the border with Haiti, and transferred land ownership to the sugar companies. Followers of the Dominican Vudú faith healer Liborio in the San Juan valley resisted the US occupation and aided counterpart rebels (cacos) in Haiti in their own war against the Americans (see Haiti).

As in Haiti, a national police force was created and used by US Marines to help fight the various guerrilla groups. Also, this US-trained militia would later play a major role in local politics.

This police force, which was later renamed the Guardia Nacional Dominicana, became an important instrument in the rise of General Rafael Trujillo. His actions would go a long way toward defining Dominican sense of national identity.

US corporate dominance

By the end of 1921, the rise in international sugar production had glutted the world market, causing prices to plummet once again. This bankrupted many local sugar empresarios, thereby allowing large American conglomerates to enter and dominate the Dominican sugar industry.

By 1926, 12 US companies owned more than 80 per cent of the 520,000 acres of land under sugar cultivation. However, unlike the Cuban immigrant planters who preceded them, the US corporations did not invest in the country but repatriated their profits, causing local resentment.

As prices declined, the US-owned sugar estates increasingly began to rely on imported Haitian labourers. This was partly brought about by a series of pay-related strikes by the migrant Caribbean-born cane cutters organized by Marcus Garvey’s international black worker rights movement, the Universal Negro Improvement Association.

In addition, the land acquired via the Land Registration Act had led to a growth of sugar production in the south-west, near the Haitian border and created an increased demand for labour.

The US-run military government greatly facilitated Haitian migrant worker involvement in the Dominican sugar industry by originating the system of regulated contract labour aimed at importing Haitians as cheap sugar cane workers for the US-owned estates. US political domination over the entire island meant that American push for labour in the Dominic Republic could be expedited through a US-managed border control. This economic migration serves as the historical background for most subsequent migration of Haitians to the Dominican Republic.

Trujillo era

US occupation ended in 1924, under President Horacio Vásquez. General Rafael Trujillo was elected President in 1930 with 95 per cent of the vote. Trujillo, who was the commander of the Guardia Nacional Dominicana, used this militia to harass and intimidate electoral personnel and potential opponents.

Trujillo professed an admiration for European fascist dictators and developed the Guardia Nacional into one of the largest military forces in Latin America. He forcibly eliminated all opposition, repressed human rights and acquired absolute control over the Dominican nation.

For 31 years Trujillo and his family established a near-monopoly over the national economy. By the time of his death the Trujillo family owned 50-60 per cent of the arable land in the country. He also exploited nationalist sentiment to purchase most of the Dominican Republic’s sugar plantations and refineries from US corporations. Moreover, the drastic anti-Haitian population purges were initiated during the Trujillo era.

Haitian massacre

With the sugar estates increasingly needing workers for seasonal labour, many Haitian migrant workers began settling permanently in the Dominican Republic.

During the mid-1930s, General Trujillo introduced a policy called the ‘Dominicanization of the frontier’. This involved changing place names along the border from Creole and French to Spanish, outlawing the practice of Vudú and imposing quotas on the percentage of foreign workers companies could hire.

Trujillo ordered the army massacre of between 15,000 and 30,000 unarmed Haitians living on the Haitian-Dominican border, justifying the action as a reprisal for Haiti’s supposed support for Dominican exiles plotting to overthrow his regime.

These acts drew international criticism but not much more. Despite the massacre, up until the late 1980s successive Haitian governments continued to sign contracts with the Dominican authorities that allowed the recruitment of Haitian cane cutters in return for a per capita fee.

Blanquismo

Some argue that the 1937 massacre of Haitians needs to be viewed in the larger context of Trujillo’s and Dominicans’, as well as the Haitian mulatto elite’s attitudes towards ‘blackness’, dating back to the colonial period.

While cleansing the dark-skinned Haitians from the frontier, during this same period Trujillo sought to increase the number of light-skinned people in the Republic. Trujillo enthusiastically promoted the policy of blanquismo or whitening, which had long been practised in postcolonial South America.

This involved inviting immigration from Europe to ‘improve’ the population mix as a means of stimulating national development. Trujillo therefore welcomed refugees from European conflicts and promoted the idea of the Dominican Republic as a European-modelled society dedicated to modernization, material progress and continued economic expansion.

The Organization of American States (OAS) finally took action against the regime in 1960 but not specifically because of the 1937 massacre or general treatment of Haitian migrants. The resolution called for a break in diplomatic relations with the country. Then, in May 1961, a group of Dominican dissidents, armed and trained in the USA, assassinated General Trujillo.

The persistence of discrimination in the post-Trujillo era

Following years of instability, the Dominican Republic managed in the ensuing decades to establish a relatively stable democratic political system. Nevertheless, the country wrestled with periods of inflation and the decline of its sugar industry, long the bulwark of the country’s economy. Notwithstanding these challenges, migration from Haiti continued well into the 1980s.

While the threat of killings and mass violence has reduced in decades, old fears of a ‘Haitian invasion’ have persisted, reflected not only in social attitudes but also in increasingly draconian government policies that have sought to redefine citizenship in increasingly narrow terms. This included the passing in August 2004 of the new Migration Law No. 285-04, legislation that cast foreign workers and migrants as foreigners ‘in transit’, preventing their children from gaining Dominican citizenship and also establishing a separate registry for children born in the country of foreign mothers without a regular migration status.

Tens of thousands of Haitians continued to be deported every year, with occasional crackdowns triggered by security concerns or violent incidents attributed to Haitian nationals. In this context, the legitimate citizenship claims of many long term Dominico-Haitians were obscured or denied. Further restrictions served to undermine their position within the country. This included, in March 2007, the Central Electoral Board’s decision to stop issuing birth certificates and copies of birth certificates to Dominicans born in Dominican territory to foreign parents, followed by its creation in April of a new registry described under Migration Law No. 285-04, commonly called the ‘Book of Foreigners’.

In January 2010, a new Constitution was approved in the Dominican Republic. Besides including severe provisions on a range of rights and freedoms, from abortion to gay marriage, it also developed additional barriers for its Domino-Haitian population to access citizenship. For the first time in the country, the Constitution denied the automatic acquisition of Dominican nationality to children of irregular migrants. While since then, amid widespread international condemnation, there have been some steps forward – for example, in October 2011 the Central Electoral Board began reissuing birth certificates – in other areas authorities continued to push large numbers of Dominico-Haitians into statelessness. The Dominican Constitutional Court’s judgment TC/0168/13, issued in September 2013, retroactively deprived hundreds of thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent of their Dominican nationality (covering the period 1929 to 2010), leaving them without citizenship.

Governance

The Dominican Republic’s National Congress consists of the 32-member Senate and the 183-member Chamber of Deputies. Members of both chambers serve four-year terms. President Danilo Medina Sanchez was re-elected in May 2016. He first came to power in August 2012, succeeding three-term President Leonel Fernandez Reyna. A constitutional change in 2015 allowed Medina to seek re-election. The current President is Luis Rodolfo Abinader Corona, who was elected in 2020.

The right to nationality is guaranteed in numerous human rights instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 15), the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 7), and the American Convention on Human Rights (Article 20). While states can regulate the acquisition and retention of nationality, they must respect fundamental human rights norms in doing so. With regard to the Dominican Republic, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in the case of Expelled Dominicans and Haitians v. Dominican Republic, explained that, when regulating the granting of nationality, states must avoid rendering persons stateless, and they must not discriminate in the enjoyment of the right to nationality.

Judgement 168/13 and Law 169

On 23 September 2013, in Judgement 168/13, the Constitutional Court of the Dominican Republic retroactively stripped more than 200,000 persons of Haitian descent of their Dominican nationality. The ruling established that people born in the Dominican Republic would not automatically gain Dominican nationality, unless their parents were also proven to be Dominican nationals. This ruling denationalized four generations of Dominicans with Haitian ancestry, who were born in the period bet

-

Groupe d’Appui aux Rapatriés et Réfugiés (Haiti)

Instituto de Investigaciones, Documentación y Derechos Humanos

Website: www.idh-rd.org.doLa Red de Encuentro Dominico Haitiano Jacques Viau

Movimiento de Mujeres Dominico-Haitianas (MUDHA)

Website: http://mudhaong.org/en/Servicio Jesuita a Refugiados y Migrantes

Solidaridad Fronteriza (SJRM)

Updated July 2023

Related content

Minority stories

View all-

15 September 2017

Denial and Denigration: How Racism Feeds Statelessness

Five organizations from Eastern Europe came together to address the growing concern of online discrimination and hate speech against Europe's biggest minority community, the Roma.

- South Asia

- Discrimination

- Minority stories

-

11 July 2016

State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2016: Focus on culture and heritage

Five organisations from Eastern Europe came together to address the growing concern of online discrimination and hate speech against Europe's biggest minority community, the Roma.

- Central Asia

- Discrimination

- Minority stories

Reports and briefings

View all-

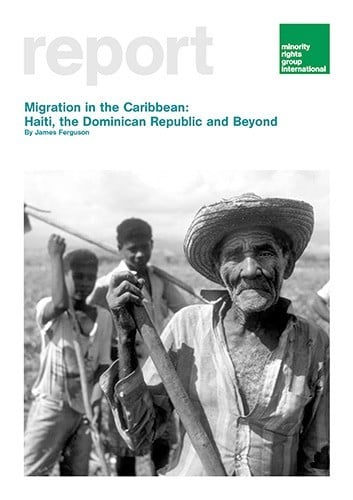

1 July 2003

Migration in the Caribbean: Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Beyond

This Report aims to cast light on the conditions experienced by often invisible minority migrant workers in the Caribbean, looking at…

-

1 June 1995

No Longer Invisible: Afro-Latin Americans Today

The distinct but extraordinarily diverse ethnic and cultural identities of Afro-Latin Americans have received little official recognition….

-

1 July 1987

The Amerindians of South America

For over 20,000 years a wealth of many cultures flourished in South America, both in the high Andean mountains and the lowland jungles and…

Films

Programmes

-

- Dominican Republic

-

- Southern Africa

Events

-

28 September 2015 • 4:30 – 6:00 pm CET

‘No nationality, no rights’: Statelessness Affecting Dominicans of Haitian descent

In September 2013, a Constitutional Court ruling deprived tens of thousands of Dominican women, men and children of Haitian descent of…

-

Video on demand

Video on demand 31 March 2016 • 7:30 – 9:30 pm BST

Premiere screening, Q&A and music performance for documentary ‘Our lives in transit’

Minority Rights Group International, in collaboration with Movimiento de Mujeres Dominico-Haitianas (MUDHA) and the production company

Don’t miss out

- Updates to this country profile

- New publications and resources

Receive updates about this country or territory

-

Our strategy

We work with ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, and indigenous peoples to secure their rights and promote understanding between communities.

-

-