Minority and Indigenous Trends 2018: Focus on migration and displacement

The chapters

MRG’s new flagship report looks at migration and displacement from a minority and indigenous perspective.

- 01

Canada and the United States: The continued struggle of indigenous communities to defend their lands

By Alicia Kroemer Across North America, indigenous peoples are still affected by the traumatic legacy of displacement from their ancestral lands, a historic expropriation that continues to undermine their wellbeing, spirituality and way of…

0 min read

- 02

Central African Republic: The difficulties of return for the country’s conflict-displaced Muslims

By Will Baxter Five years after the outbreak of civil conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR), a large proportion of its Muslim minority – an estimated 80 per cent of whom had been forced out of the country in the first months of…

0 min read

- 03

Dominican Republic: Stripped of citizenship, the deportations of ethnic Haitians continue

By Kate George Dominicans of Haitian descent as well as Haitian immigrants have suffered a long history of discrimination, punctuated by outbreaks of targeted violence and detentions. Recently, however, they have faced further difficulties…

0 min read

- 04

Guatemala: Violence and discrimination drive indigenous migration elsewhere

The legacy of Guatemala’s brutal civil war, which saw security forces target thousands of indigenous citizens in a campaign of sexual assault, torture and mass executions, continues to be felt today, with many communities still subjected to…

0 min read

- 05

India: Living on the fringes of Delhi – the Ghiyaras of Rangpuri and their continued exclusion

By Sajjad Hassan For many of India‘s indigenous communities, poverty and displacement from their ancestral lands have driven large numbers to move to urban areas in the hope of securing education or employment there. All too often,…

0 min read

- 06

Israel: An uncertain future for thousands of African asylum seekers caught between detention and deportation

By Charlotte Graham Across the Middle East, thousands of sub-Saharan migrants – including workers stranded by conflict, asylum seekers fleeing violence and others attempting the dangerous journey to Europe – have become some of the…

0 min read

- 07

Italy: Another year of forced evictions for the country’s Roma

By Catrinel Motoc Roma, one of Europe’s most marginalized minorities, continue to be targeted in many countries with forced evictions – a situation that locks them into a cycle of displacement and human rights violations that affect…

0 min read

- 08

Jordan: The struggles of Bani Murra, one of Syria’s most marginalized communities, now displaced as refugees

By Elisa Oddone With more than 5.6 million Syrians now living outside the country, predominantly in neighbouring Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, the conflict has created a vast refugee population facing poverty, discrimination and insecurity….

0 min read

- 09

Morocco: An Amazigh community’s long wait for water rights

By Jasmin Qureshi The environmental impacts of mining are a major cause of displacement for minorities and indigenous peoples across the world, with many unable to secure compensation or protections due to discrimination. But in Morocco, a…

0 min read

- 10

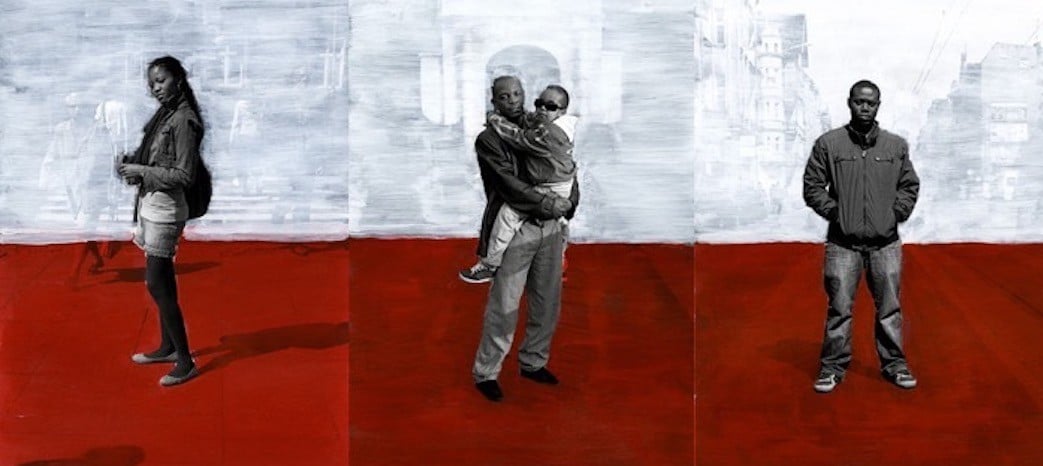

Poland: Sub-Saharan Africans and the struggle for acceptance

By Konrad Pędziwiatr and Bolaji Balogun Poland, a country with a predominantly white population and, until recently, limited immigration, has seen the growth in recent years of a sizeable sub-Saharan African minority. This community, though…

0 min read

- 11

Russia: Migrants from Central Asia struggle with documentation in Krasnodar Krai

By Semyon Simonov Millions of migrants reside in Russia, many of them from Central Asia, with a particularly large proportion originating from Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. They play a vital role in the Russian economy and undertake a range of…

0 min read

- 12

South Sudan: Displaced again by conflict, the Shilluk community faces an uncertain future

The conflict in South Sudan that began in December 2013 after clashes between the forces of President Salva Kiir, a Dinka, and his then Vice President Riek Machar, a Nuer, quickly took on strong ethnic dimensions and has seen thousands of…

0 min read

- 13

Challenging colonial legacies: Minorities and indigenous peoples’ struggle for inclusion in Africa

By Hamimu Masudi The dubious origins of statehood in Africa have been clear to anyone interested in understanding and explaining contemporary development challenges on the continent. By the stroke of a pen at a Berlin conference in 1884, the…

0 min read

- 14

Sri Lanka: The gentrification of Slave Island – A way of life under threat for Colombo’s Malay population

By Abdul Halik Azeez While much attention has focused on the decades-long civil war in Sri Lanka and the legacy of conflict, which formally ended in 2009, the country’s inequitable development since then has deepened discrimination…

0 min read

- 15

Thailand: As violence in the south continues, emigration from the region increases

By Nicole Girard The protracted conflict in Thailand‘s deep south, since reigniting in 2004, has cost some 7,000 lives and is now driving a slow exodus from the region. Initially Thai Buddhists, a minority in the majority Muslim region…

0 min read

- 16

Uganda: Decades of displacement for Batwa, uprooted in the name of conservation

By Emma Eastwood Uganda‘s Batwa, an indigenous people who have suffered a long history of discrimination, have been displaced for decades from their ancestral land. Like other indigenous communities across Africa, despite stewarding the…

0 min read

- 17

United Kingdom: Rohingya refugees find a safe home in Bradford

By Jasmin Qureshi In 2017, a brutal military campaign displaced more than 700,000 Rohingya from Myanmar and killed thousands more, with security forces systematically targeting communities with arson, rape and mass executions. The latest…

0 min read

- 18

United States: Against a backdrop of growing hostility, undocumented migrants in Oregon are taking a stand

By Araceli Cruz and Mariah Grant Since taking office in January 2017, following a protracted political campaign that exploited and promoted anti-immigrant sentiment among sections of the American public, US President Donald Trump has passed…

0 min read

-

By Alicia Kroemer

Across North America, indigenous peoples are still affected by the traumatic legacy of displacement from their ancestral lands, a historic expropriation that continues to undermine their wellbeing, spirituality and way of life to this day. But despite a range of protections now in place to prevent further abuses, communities are still facing renewed threats from big business – and national governments are doing little to stop them.

For indigenous communities in Canada and the US, land, environmental protection and human rights are intrinsically linked: land is the foundation of their livelihood and spirituality. It is for this reason that colonization was such a detrimental force when Western powers seized ownership of land and drove indigenous peoples from their ancestral territories. In Canada and the US, early European peace treaties forced the surrender of vast areas of land, displacing tribes onto reservations – an act described by Judy Wilson, Chief of Neskonlith Indian Band, as the ‘biggest land grab in history’.

Today, however, many of these reservations face a new threat: corporate colonialism. Large extractive industries, through the building of gas and oil pipelines, could jeopardize their future. Use of land for these purposes is regarded by indigenous communities as theft, resulting in widespread environmental degradation and, in some cases, displacement of their communities. In many cases these developments have been met with indigenous resistance and protests that, at considerable personal peril to participants, have highlighted the dangers posed by the extractive industries to their homelands.

Standing Rock: the violent repression of the largest indigenous protest in living memory

LaDonna Bravebull-Allard, a Lakota Elder activist and one of the founders of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protests at Standing Rock, managed to draw unprecedented global attention to the dangers of illegal development on indigenous territory. The Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) protests began in 2016, after the US government approved construction of a 1,886 km crude oil pipeline from North Dakota to Southern Illinois, which would be routed under rivers and sacred burial grounds on the Standing Rock Native Reservation.

The protests garnered international coverage and went on to become the largest gathering of Native Americans in the US in more than a century. Despite this success, however, the federal government largely ignored the demonstrations and a private security firm was hired to drive peaceful protesters out, using rubber bullets, water cannons and attack dogs. This weaponized response to peaceful protests left over 200 people wounded, some with life-altering injuries, while several other protesters are now in jail awaiting federal sentences.

‘Right now,’ says Bravebull-Allard, ‘we still have people in jail, going to court, people who will be facing federal charges. We have a list of the journalists and medics who were shot, we have people with permanent injuries from the mace, rubber bullets, grenades and water cannons.’

While many across the world supported the demonstrations at Standing Rock, the lasting injuries suffered by protesters and the continued risk of jail sentences for others have been largely overlooked by the mainstream media. With the Trump administration now pushing the pipeline’s development in the face of continued environmental concerns, Bravebull-Allard states that there may already have been oil leakages on her ancestral homeland.

Kinder Morgan Pipeline: Canada’s Secwepemc community protests the forcible development of their land

Further north, in Canada, indigenous communities are facing a similar uphill battle against the political and corporate powers behind the Kinder Morgan Pipeline, a development that would carry crude and refined oil from Alberta to the West Coast of Canada for export to global markets. The project, despite court challenges filed from myriad indigenous peoples, has been approved by the federal government. First Nations representatives claim the government has not properly consulted the communities who would be most affected by the pipeline, in direct violation of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

As highlighted by Chief Judy Wilson (left), the pipeline will go directly over Secwepemc land, home to some 10,000 people. ‘The Kinder Morgan approval by the federal government is the biggest contradiction yet in how they are implementing the UNDRIP and not respecting our human rights,’ she says. ‘In our interior nations we have not consented to the pipeline, the Secwepemc people have not sanctioned this project and Kinder Morgan has no consent from the Secwepemc people.’ Wilson criticizes the Canadian government for its ‘masquerading’ display on the global stage, explaining that on an international level they proclaim their commitment to indigenous peoples and free, prior and informed consent, but behind closed doors they are not true to their word. ‘They do not have our free, prior, and informed consent with Kinder Morgan, nor with our interior Secwepemc people, nor with many of the coastal nations – and that must stop. We are going to do whatever we have to do to uphold our stands, uphold our title, and uphold our rights.’

The violation of these rights is an area of particular concern for Secwepemc who, like other indigenous peoples in Canada, are still struggling with the legacy of their historic displacement from large swathes of their territory. These tensions have persisted in recent years as new developments have been constructed in territory traditionally belonging to the community, such as the controversial, multimillion dollar Sun Peaks ski resort approved in 1997 on Mount Morrissey, regarded by many Secwepemc as sacred land. The Kinder Morgan Pipeline therefore represents the latest chapter in a long process of displacement and dispossession.

Nestlé and the fight for water in Wintu territory

As Chief of the Winnemem Wintu tribe, along the McCloud River watershed in Northern California, Caleen Sisk (left) is a tireless activist on behalf of salmon restoration, water protection and the right to clean drinking water. She is also the Spiritual and Environmental Commissioner for ECMIA, an international network for indigenous women. She has been at the forefront of her community’s struggle to protect their precious natural resources from the attempts of Nestlé and other private corporations to bottle water on their land.

‘We have had the problem of Nestlé coming into some of our small mountain communities,’ says Sisk. ‘This impacts all people; when you tap into high mountain water sources, everything downstream is affected. This worries us because it affects our fish, it affects our drinking water and affects how much water gets to everything else that needs it. Whenever these water-bottling companies come in they contaminate half the water that used to be drinkable, they bottle the other half of the water and ship it to other parts of the world, and this water will not go downstream, and we do not get any of the water they are bottling. The rest is polluted.’

The McCloud River watershed is an area already struggling with drought, a situation only worsened by the activities of water-bottling companies on Wintu land. If this issue goes unaddressed, the lack of adequate clean water could in future lead to the forced displacement of the community. The tribe has therefore found itself locked in a continuous battle with corporations misusing their water sources, resulting in devastating impacts and severe environmental degradation to their sacred territories. While Chief Sisk and her community launched a successful legal action against Nestlé, another water-bottling business has taken its place: a lawsuit was issued against the company in question, Crystal Geyser, in April 2018 to challenge the approval of an industrial waste discharge permit to the company – a decision that Windu believe will lead to further contamination.

Protecting the environment through indigenous land rights

These case studies, spanning a number of different communities across North America, highlight the persistent difficulties that indigenous peoples face in ensuring their land rights are protected, despite the apparent progress made in recent years after decades of official discrimination, including displacement from their ancestral territories. Today, the depredation of land, water and forests by a wave of corporations, often with active government support, poses a profound threat not only to the future survival of these communities and their way of life, but also the fragile natural environments on which they depend.

As caretakers, gatekeepers and protectors of the earth and its resources, indigenous peoples in North America and elsewhere have valuable lessons to impart on the protection and conservation of the environment. ‘As indigenous people,’ says Bravebull-Allard, ‘we hold the last of the pristine land. We hold the last of the clean water.’ The encroachment on these reserves by big business is a concern not only for the communities affected, but all humanity. ‘As the corporations come in, whether for deforestation or oil or minerals, all the developments, they are taking the last of what is most precious. It’s not most precious to just indigenous people, it is to all people. We must be able to hold these areas for all people to live.’

Photo: Members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe hold a protest at the Sacred Stone Camp near Cannonball, North Dakota, US, to oppose the planned Dakota Access Pipeline. Credit: Panos / Hossein Fatemi.

-

By Will Baxter

Five years after the outbreak of civil conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR), a large proportion of its Muslim minority – an estimated 80 per cent of whom had been forced out of the country in the first months of fighting – are still unable to go back to their homes. In many areas, Christian militias known as anti-balaka remain active and properties belonging to Muslim families have either been taken over or destroyed. This uncertainty is preventing many from returning to their lives, leaving a legacy of conflict that has yet to be resolved.

In the CAR, Muslims attempting to return to their communities in the south-west of the country face numerous obstacles to rebuilding their lives and businesses. Most also find that they are expected to suffer a range of injustices and inequalities in silence, lest they risk upsetting a tenuous peace with local Christians.

The recent conflict in CAR was initially sparked at the close of 2012 by a coalition (‘Séléka’) of rebel groups which launched an offensive in the north against the forces of then President François Bozizé. The Séléka came mainly from ethnic groups in the north of the country, unified loosely by their opposition to Bozizé and their Muslim faith. As they advanced south, briefly seizing control, the conflict increasingly acquired ethnic and religious dimensions. Séléka raids particularly targeted non-Muslim areas. Christian communities began to form or activate existing anti-balaka (‘anti-machete’) groups to protect their areas. While anti-balaka militias may initially have fought Séléka forces, they began attacking Muslim communities more generally.

From late 2013 to early 2014, as a campaign of ethnic cleansing was perpetrated against the Muslim minority in CAR, hundreds of thousands fled to neighbouring countries, including Cameroon, Chad and the Democratic Republic of Congo. More fled during subsequent waves of violence in 2016 and 2017. By the end of 2017, there were nearly 690,000 internally displaced and over 540,000 refugees in neighbouring countries. Finding the conditions in refugee settlements difficult and untenable, many – mostly men – have returned to south-western CAR since late 2014, despite concerns about security.

Though conditions vary considerably from place to place, the situation for returnees is typically fraught. These challenges have very real implications for the reintegration of returnees and the future stability of the country.

Nola: peace, but at a cost

Before fleeing to Cameroon in 2014, Adamou, 52, owned four houses and two large stores, one in Nola and one Bayanga. When he left, his stores were looted and his homes taken over by Christians. He returned to Nola in 2015 but says he has struggled to get his business back on track.

‘When the conflict broke out, we had to run away quickly. We locked up our stores and left everything behind. At the time, we just needed to make sure we were safe. But the local population came and took everything. I lost both my stores. I lost all my merchandise,’ says Adamou.

When Adamou left CAR, he was a successful businessman, and was able to support a large family, including three wives and 17 children, ranging in age from 3 to 21. But Adamou was forced to make the difficult decision to leave them behind in Cameroon due to his concerns for their safety in CAR, as well as the financial constraints attached to bringing them back to Nola. Now his only income is from a small pharmacy that generates little profit. ‘At my old stores, I sold a wide range of merchandise. I would buy items in Cameroon and Nigeria and sell them here. Now my financial situation is dire.’

Hamadou, a Muslim returnee, poses for a portrait at his small stall in Nola town, CAR. Credit: Will Baxter. For 35-year-old Hamadou, returning to Nola after a two-year absence (he left in 2014 and returned in 2016) has also involved a major step down in status. All the shops in the town’s primary trading street have been taken over by Christians, forcing Muslims to open up their businesses on side streets and in less frequented neighbourhoods.

‘My old store was big and in a good location, right on the corner of the main street. Each month we went to Cameroon and bought items to sell here. We had good stock,’ says Hamadou. ‘Now I’ve hired this small shopfront for 15,000 CFA (US$27) per month. Sometimes I make about 2,000 CFA (US$4) per day in profit. Sometimes I lose money. There just isn’t enough interest in what I have to sell,’ he said, which includes small electronics like lanterns and flashlights.

Like many returnees, Hamadou also has the responsibility of sending remittances abroad to his family. ‘I am obliged to send money to my parents in Cameroon. Sometimes it’s 15,000 CFA, sometimes just 2,000. I do my best. But I have financial problems. I have to buy items on credit and pay the lender back on time.’

Abdramane, the coordinator for Muslim returnees in Nola, says that in addition to loss of livelihoods, housing is one of the other major issues that returnees face. ‘The Muslims’ houses were taken over by the residents here. Some left when the Muslims came back, but some ask the Muslims to pay them to leave. They say they are like the “guardian” of the house, so before leaving they have to be paid off. These guardians ask for a lot of money, sometimes for as much as 1 million CFA (US$1,830).’

Abdramane says that most returnees cannot afford to pay the exorbitant amounts demanded by these so-called caretakers and end up calling the police to help negotiate a solution. The authorities have been very helpful in this way, Abdramane said, and usually a more reasonable price is agreed upon, though this can sometimes be as high as 200,000 or 300,000 CFA (US$370 to $550).

Abdramane, the coordinator for Muslim returnees in Nola, walks through Nola town, CAR. Credit: Will Baxter. Adamou has only been able to reclaim one of his properties. ‘My houses were “protected” by the local people. But those who protected the houses, now they are asking for money. Unfortunately, I am moneyless. I don’t have enough to give them,’ he says. As a consequence, three of Adamou’s houses are still occupied by Christians, though he managed to scrape together enough to buy back the right to occupy one of his homes. ‘I had to give them 50,000 CFA (US$92) to get them to leave,’ he says.

Hamadou’s experience was different. ‘When I fled, I chose an old man to secure my house. When I got back, I discovered that the old man had sold all of my possessions. When I asked him to pay me back, he was unable to pay and he ran away.’

Despite the various hardships they are facing, Hamadou says that the most important thing is that the relationship between Muslims and Christians remains peaceful. ‘Right now, we don’t have any problems. We are living side by side with the Christians,’ he says.

Garba has worked hard to help establish that peace. ‘There is open contact between myself and the anti-balaka (who now refer to themselves as a “self-defence group”),’ he said pointing out that the local former anti-balaka commander, Ferdinand Ndobadi, has been helpful in ensuring security.

‘This is a safe town, a guns-free town. There are no problems now. The issue is that there is a lack of financial support for sensitization,’ says Ndobadi, coordinator of the Shanga-Mbaire Self-Defence Group.

‘We want to maintain peace in order to promote economic activities. So we need the Muslims to come back in order for us to live together. One group needs the other,’ he says. ‘We understand now that it was political events that divided us. We understand now that we were manipulated by the politicians.’

Berberati: living with the legacy of conflict

Mamadou, a Muslim returnee, in Berberati, CAR. Credit: Will Baxter. Returnees like 47-year-old Mamadou say the situation in Berberati is more bleak. Mamadou fled to Cameroon in February 2014 and returned to CAR in November 2016.

‘All of our houses were destroyed. Our businesses were destroyed. We do not have freedom of movement. We cannot conduct our business freely. Members of the local population sometimes threaten us about our business activities. If we have a problem and want to go to the law, this will just create another problem,’ he says.

Before fleeing CAR, Mamadou had a stall at the market in the centre of town. Like most returnees, he has struggled to get back into business and remains separated from his family of 14. ‘I lost my stall when I fled. Of course, being away so long, my merchandise was looted. I am trying to look for the means to make a business again, but for now I have not been able to,’ he says. ‘My family has had to stay in Cameroon because I cannot afford to bring them back. There is no security here. Even on the way back, they could face dangers.’

Mamadou says that, unlike Nola, Berberati is not safe for Muslims. ‘The Muslim leaders and anti-balaka leaders sat down together to make peace, but still we are not free. Sometimes returnees are attacked with knives. Sometimes armed people have stopped us and robbed us, demanding money. Anti-balaka youth carry out armed robberies. They will take your motorbike and then demand that you pay them to get it back. But we have no recourse. There is nothing we can do,’ he says.

Maria, a Muslim returnee, is photographed in Berberati, CAR. Credit: Will Baxter. Maria, a 42-year-old widow whose father is Muslim and whose mother is Christian, has ended up living in Popoto quarter of Berberati because she cannot return to Baleko town (25 miles south-east of Berberati), where she lived before fleeing to Cameroon in 2014. Her husband was shot and killed by the anti-balaka when they tried to flee Baleko. She returned to CAR in November 2017, but when she arrived in Baleko she discovered that her home had been destroyed. Fearing for her security, she left immediately.

Berberati does not feel very welcoming either, she says. ‘My children have problems with local children when they walk around town,’ she said, adding that her 14-, 10- and 8-year-olds have to deal with regular harassment and discrimination. ‘Muslim children have to walk on the other side of the street from the Christian children. The locals say bad things to my children. They say “You should have stayed away. It is no use for you to come back here. You don’t belong.”’

Maria said that freedom of movement is a major issue and that her ability to move has been further constrained because she lost her ID card when she fled her home. ‘We lost all of our documents. This causes big problems when we want to travel or even just move from one town to the next.’ More everyday concerns also take their toll. ‘Now we have problems getting money, food and clothes. I need medicine for back pain. My children have had malaria and some are anaemic. But I cannot afford medical exams. I can only afford to buy Panadol tablets and sometimes I just make do with traditional medicines and make a tea from leaves and bark.’

Maria also laments the fact that her children are missing out on the opportunity to attend school. ‘I want my younger children to be able to continue their studies, but the fees are too much,’ she says.

Haroun, a Muslim returnee, poses for a portrait in Berberati, CAR. Credit: Will Baxter. For the younger generation, this inability to further their education will likely have long-lasting impacts. Haroun, 22, has also had to put his studies on hold. He fled Bania town (29 miles from Berberati) for Chad in April 2014, returning in March 2016. He was forced to relocate to Berberati in November 2017 after he and a friend were attacked by a group of anti-balaka youth.

‘One night I was coming back to Bania with a friend. As we arrived, a group of anti-balaka youth stoned us with rocks and tried to beat us with wooden clubs. Thanks to the police, who chased them away, I was able to get back to Berberati safely.’

Haroun stopped studying when he was 16. ‘I would like to finish my studies, and more than anything I would like to attend university in Bangui. But I try not to dream about this too much. There are many obstacles to me continuing my education,’ he said, such as lack of money. ‘I was a good student and sometimes I got good grades. If I had the opportunity, I would continue my studies at university. To be honest, I would study anything.’

Back in Nola, Abdramane says he will continue to do his best to maintain peace and assist returnees in any way he can. ‘But I worry a lot about the risks I am taking and the risk I am putting myself in as the focal point, giving information to people about what is happening in Nola. All eyes are fixed on me, so I can honestly say that my life is in danger,’ he says. ‘There are still enemies of peace here … bad people with bad intentions. These are the ones who worry me.’

Header image: A Muslim girl walks down a street in Nola town, CAR. Credit: Will Baxter.

-

By Kate George

Dominicans of Haitian descent as well as Haitian immigrants have suffered a long history of discrimination, punctuated by outbreaks of targeted violence and detentions. Recently, however, they have faced further difficulties amidst an official crackdown that has seen thousands deported from the country, including many with valid claims of citizenship. This latest episode has brought the country’s deep-seated racism to the surface – and left those still in the country at risk of persecution.

Despite the decades of discrimination they have experienced in the DR, from official persecution to vigilante attacks, thousands of Haitians have continued to settle in the country to work on plantations or in construction. But though they have played a crucial role in these sectors and the wider Dominican economy, their public vilification has persisted – notwithstanding the fact that a sizeable number have been settled for generations and have valid claims to Dominican citizenship.

Their problems intensified in September 2013 when the DR’s Constitutional Court issued judgment TC/0168/13, stripping hundreds of thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent of their Dominican nationality. This included all Dominicans whose parents were not born in the DR and was retroactive for anyone born in 1929 or later. It ruled that, in line with the 2010 National Constitution, all children born in the DR to foreign parents in transit or residing in the country irregularly would not receive Dominican nationality.

This judgment has paved the way for the mass deportation of many Dominicans of Haitian descent and Haitian immigrants to Haiti, as well as exacerbating the already entrenched discrimination experienced by these individuals. Despite some steps to resolve the situation, including the passage of a highly flawed Naturalization Law in May 2014, thousands of Dominicans of Haitian descent have yet to regularize their status. Besides effectively rendering them stateless, this has left many at risk of deportation to Haiti – a country some have never even visited. The legislation has been condemned by, among others, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), which has highlighted the acutely discriminatory nature of the ruling and its disproportionate impact on Dominicans of Haitian descent, many of whom have been left unable to access essential services such as education and health care.

Although the Dominican government implemented a temporary 18-month suspension of mass deportation in December 2013 in order to allow undocumented foreigners to regularize their status, these deportations resumed in June 2015. Since then, thousands have been deported from the country, including many with valid claims to Dominican citizenship, and the situation for those who remain in the country has deteriorated dramatically.

In a recent interview with staff at MUDHA (Movimiento de Mujeres Dominico-Haitianas), a non-governmental organization providing social and legal assistance to Dominicans of Haitian descent facing deportation and discrimination, Legal and Human Rights Area Coordinator Jenny Carolina Moron Reyes describes how community members have been specifically targeted by the authorities. ‘Community information is spreading on police raids and migration officers entering communities with the aim of deporting foreign persons,’ she says. ‘The national press has highlighted the deportation process that is being carried out by the national authorities, as well as xenophobic and discriminatory actions towards Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent, especially women.’

This official crackdown has been accompanied by widespread popular xenophobia and outbreaks of anti-Haitian violence by vigilantes that have forced many to leave the Dominican Republic. There has also been an increase in xenophobic attacks on Dominicans of Haitian descent by nationalist groups in the country. This was recently exemplified by aggressive protests in May 2018 that disrupted the IACHR’s 168th session in Santo Domingo. As a result, the IACHR was prematurely forced to close the meeting to ensure the safety of its members. Elsewhere, border provinces such as Pedernales have experienced a rise in xenophobic attacks and aggression towards Dominicans of Haitian descent and Haitians. Nationalist groups have also used social media platforms to incite hatred and discrimination towards these groups.

While efforts to resolve the status of Dominicans of Haitian descent are ongoing, they continue to be informed by a fundamental reluctance to recognize Dominicans of Haitian descent as full citizens. Moron Reyes points to the creation of the so-called ‘book of foreigners’ and other registries where Dominicans of Haitian descent are listed as reflecting broader attitudes of what she describes as ‘state encroachment’. ‘They are portrayed by the Dominican government as a solution to the problem of statelessness,’ she says. ‘The fact remains that while the book provides individuals with an identity, it can still leave them stateless.’

While these issues are specific to Dominicans of Haitian descent, their situation and the treatment of Haitian immigrants more generally are interlinked. The denial of citizenship and the official crackdown on immigrants are both reflective of the broader racism all groups have suffered in the country. Even if the situation of the Dominicans of Haitian descent minority is eventually resolved, without a sustained commitment at all levels of society to address this prejudice they will remain second-class citizens in their own country. In the meantime, the deportations continue.

Photo: A still from Minority Rights Group International’s film about Dominicans of Haitian descent living with statelessness in the Dominican Republic. Credit: MRG.

-

The legacy of Guatemala’s brutal civil war, which saw security forces target thousands of indigenous citizens in a campaign of sexual assault, torture and mass executions, continues to be felt today, with many communities still subjected to very high levels of violence. For indigenous youth, in particular, the presence of criminal gangs is a frequent source of danger – leaving many with no choice but to flee the country.

Raised by his mother and grandfather, Jorge C. spent much of his teenage years alternating between hiding out in his family’s small shack and working in the fields of his home in San Juan Ixcoy (Yich K’ox), in the department of Huehuetenango in Guatemala, where he cultivated and harvested potatoes. His home region of the Sierra de los Cuchumatanes is the highest non-volcanic mountain range in Central America.

Like many other indigenous inhabitants of Guatemala’s Western Highlands, 19-year-old Jorge is illiterate and grew up in a multilingual household. His mother speaks both Spanish and Mam and washes clothes for a living.

Jorge, his brother, and his two sisters were raised by his single mother. He began working in the fields at age 12. ‘We are campesinos,’ he said. ‘I did not have the opportunity to continue in school because I had to help support my brother and sisters to survive.’ He earned roughly 350 quetzales (US$47) per week.

By the time he was 14, the local branch of the 18th Street gang targeted him. They wanted him, he says, to sell drugs. A friend of his had already joined and was serving as an informant of sorts, tipping off other members as to Jorge’s whereabouts and activities. At first, they acted as if they were trying to simply befriend him.

‘I am an easy target,’ Jorge said. ‘I am more vulnerable because I do not have a father. Where I am from in Guatemala, gang members hang out on the corners, often outside the school. They smoke drugs and sell them. One day they told me that we had to go to a bridge to pick up a shipment. I was confused … They gave me a backpack and said I had to sell drugs by the school.’ The bag contained marijuana.

Jorge tried to escape by running away. He was badly beaten.

Upon arriving home, he told his mother what had happened. She wanted Jorge to tell the local police. He refused. ‘The auxiliary police have a giant tank of cold water,’ he explained. ‘They will throw you in for 20 minutes at a time, and then drag you out and beat you. After they beat you, they will throw you back in again for 20 minutes, and then beat you again.’ Furthermore, he believed he would not be taken seriously. ‘The police don’t listen to us as indigenous people – they do not care about us.’

While Jorge’s community is impacted by narco-trafficking and gang activity, the population of the region – almost entirely by indigenous Maya, Mam and Akatek – has also long been subject to discrimination. During Guatemala’s 36-year civil war, when the military targeted entire indigenous communities indiscriminately in its brutal counter-insurgency, many of Huehuetenango’s inhabitants were forced to flee. The Guatemalan Truth Commission Report subsequently identified indigenous groups as victims of genocide perpetrated by the government. Across the country, 83 per cent of the roughly 200,000 wartime casualties were indigenous Guatemalans. In 1999, when a voluntary repatriation agreement was passed, tens of thousands of displaced Q’anjob’al, Mam and Chuj returned to Huehuetenango. There was little work to be found, however, leaving many in a state of continued insecurity and deprivation.

Today, more than two decades after the formal end of the civil war, the long history of indigenous exclusion continues: four out of five indigenous Guatemalans live below the poverty line, with limited access to health care, education and other basic services. The political disenfranchisement of the indigenous populations in Guatemala’s Western Highlands, though acute, is also prevalent across the country as a whole. For the 2016–20 legislative term in the Guatemalan Congress, only 19 out of the 158 legislators identified as indigenous, or 12 per cent, despite indigenous peoples comprising between 40 and 60 per cent of the total population. At the local level, this leaves indigenous youth like Jorge with little in the way of official protection when faced with violence or intimidation.

When gang members followed Jorge home from work in the fields, his uncle and grandfather took up their machetes to ward them off. ‘My family wanted me to stay hidden as much as I could,’ he said. ‘I stayed like this for around two months. When I finally began leaving the house, they grabbed me on the street and demanded to know where I had been … I refused to tell them. They started punching me, and that is when someone cut my hand.’ Afterwards, the teenager stayed inside for a year.

When he finally left his house, Jorge was seized by the gang again. ‘They threw me in the mud, and cut my mouth with a knife,’ he recalled. ‘It was a message: that this is what happens if you talk to the police. They told me that I could expect more beatings, if I continued to refuse to join them, and that next time I would suffer worse.’

Then 15, Jorge decided to continue working in the potato fields with his uncle, choosing to leave the house early each morning under the cover of night and returning after dark. He stayed inside the rest of the time. Eventually, he says, he made the mistake of going to a local store to buy bread. There he encountered his friend, who was a member of the gang. ‘He told me that if I continued to refuse [to join] the gang, then the main guy in charge was going to order that my hand be cut off,’ Jorge said. ‘I was very scared.’

When Jorge’s younger sister was raped by a gang member in retaliation for his refusal to join, he finally decided to flee. ‘I could not stay in Guatemala any more because the gang would never stop,’ he said. ‘Not only was I afraid for my life, but also my family.’

Jorge travelled north to the Guatemala–Mexico border and took a job as a farm worker. It was hard to find a job because of his age and undocumented status in Mexico. Six months after his arrival in Chiapas, the gang learned of his whereabouts. Strangers pretending to be family members came asking around for a young man with scars on his mouth and hand. ‘They went from house to house trying to get information about me,’ Jorge recounted.

His boss suggested requesting asylum in the United States. Jorge initially didn’t like the idea, but began to consider it. ‘The idea of going to the US scared me,’ he said. ‘I am a quiet and shy person.’

In early August 2017, Jorge arrived in Tijuana, and ended up at Casa YMCA, the city’s only shelter for under-age minors. Since 1991, the shelter has helped more than 59,000 unaccompanied migrant youth. According to shelter director Uriel Gonzalez, youth who pass through are able to come and go at will. A staff social worker helps under-age migrants understand their rights and their options. During Jorge’s month-long stay at the shelter, he remained inside, fearful of going out. He met a lawyer from the non-profit organization Al Otro Lado, who explained the US asylum process and agreed to represent Jorge pro bono.

In early 2018, Ramos helped Jorge turn himself in at the border between Tijuana and San Diego. His asylum application is pending. It will likely remain in limbo for years. His odds are slim. According to data compiled by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a data-gathering organization at Syracuse University, almost 80 per cent of individuals who fled Guatemala and requested asylum were denied between 2011 and 2016.

‘I am begging for the protection of the United States,’ Jorge says. He is currently working as a gardener. He believes he will die if he is returned to Guatemala. ‘I called home to my mother to get news from home, and she told me that my cousin was killed this week by the gang. He was walking home on his way home from playing soccer. The gang beat him, tortured him, cut off his fingers, and then killed him. We are terrified … I do not think about the future any more.’

-

By Sajjad Hassan

For many of India‘s indigenous communities, poverty and displacement from their ancestral lands have driven large numbers to move to urban areas in the hope of securing education or employment there. All too often, however, these marginalized communities find their situation replicated in cities as they struggle with evictions, segregation and continued barriers to accessing even the most basic services.

Rangpuri, in south-west Delhi, a stone’s throw from the sprawling Indra Gandhi International airport and not far from the gleaming business district of Gurgaon, is typical of the fringes of India’s national capital. New and upcoming apartment blocks – in various stages of construction – crowd the skyline, built to house the multitudes that pour into this ever-growing city. Amid the dusty landscape, in what were once low-lying hills before the scramble for urban growth consumed the area, sits Rangpuri Pahari. Today, the surroundings have been reduced to a dumping ground for construction waste and litter.

Rangpuri Pahari is home to a community of Ghiyaras, a nomadic people, now settled, having migrated to Delhi’s outskirts from neighbouring Rajasthan in 1994. Tarpaulin tents and makeshift cabins, lining narrow alleys, make up the settlement and house around 200 families. Towards the end of the afternoon, children run about as the men, back after the day’s work, sit in a circle making small talk and smoking hookah (water pipe), while the women light their fires and begin to cook the evening meal.

Basanti Devi, baking rotis on her wood stove, describes the everyday difficulties for Rangpuri’s residents. ‘This was barren land,’ she says. ‘We settled it, when we came here many years ago. But it remains inhospitable. The government has done nothing for us. We have no water supply, no toilets, no electricity.’ Water in particular is a serious issue: while a municipal tanker makes the rounds once a week, the water it provides is nowhere near enough for the community and so residents are forced to buy water at considerable expense. As a result, they are only able to shower once a week. ‘Children are made fun of in school because they are not washed. And lack of toilets of our own, and disappearing wood cover all around, due to non-stop developments, means we often have to wait until nightfall to ease ourselves. There have been many cases of children being victims of snake bites.’

Ghiyaras’ access to basic services and social security programmes is practically non-existent. The menfolk, smoking in a circle, note that other services too are scarce. And while identification documents are now common across the country, due to the government’s drive to formalize and connect all services, this is not the case for the hundreds of Ghiyaras living in Rangpuri. Their lack of identification documents locks them out of many services and social security benefits – most of which are now linked to biometric identification processes. Their situation is made even worse by the fact that they also do not possess ‘caste certificates’. These documents serve as passports to India’s elaborate system of affirmative action policies, including quotas in educational institutions and public sector employment, as well as access to social security programmes: without them, Ghiyaras are more or less unable to secure any of these benefits.

Their efforts to regularize their status have so far proved unsuccessful, obstructed by arduous and expensive bureaucratic hurdles. ‘We keep trying to obtain caste certificates too from the government, but there is no progress,’ says Satish Vaidji. ‘Patwaris [land revenue officers, authorized to confirm residence] make us go round and round in circles, asking for recommendations from local legislators and senior officers, each of which demands large sums of money as bribes, to do what they are supposed to do. We have had enough.’

Without identification documents or caste certificates, Ghiyaras remain trapped in their present state of exclusion, with little chance of escaping their predicament. There is no government school in the vicinity. A few students have recently managed to obtain admission to a primary school some distance away, but for the most part children in the settlement while their time away, waiting for the moment when they will themselves join their parents in the gruelling, poorly paid work on which the entire community depends. For the boys, this means hard physical labour on construction sites or occasionally falling back on traditional occupations, such as drumming at wedding ceremonies and serving as earwax removers. The girls, on the other hand, help with domestic chores and join their mothers as rag-pickers or domestic help in the houses of the middle-class families in apartment blocks nearby. During their short time in Delhi, Ghiyaras have experienced the full extent of what poverty in urban India can entail.

Another fundamental problem for Rangpuri’s Ghiyaras is their lack of title over the land they occupy and have made their home for over two decades. Dhanpat Pradhan, the community chief, reports that as efforts to secure recognition have stalled repeatedly, investors have begun to circle their land. ‘We have tried many times to get the government to give us title to land, so we could live securely, but no one listens to us. We are tired. And with property developers looking for more opportunities for newer building projects, they are always putting pressure on us to vacate the land. These developers are rich and powerful. They are able to bribe government officials, to deny us our rights and get them to force us to vacate.’ In recent years, their tactics have become more openly coercive, including threats of violence. ‘Initially the developers offered us money to leave. When we did not move, they began using threats and intimidation. In 2014, there was trouble, with property developers attacking us. The police and administration did not provide us with any support.’

Earlier, in 2013, the group had approached the courts to resolve the land title issue and managed to get relief in the form of an injunction against attempts by developers to force the community to vacate the site until the matter was settled amicably. This has eased the pressure on the community and is the only silver lining, residents said, in the dark cloud of their near-complete exclusion.

Ghiyaras are among India’s most marginalized, one of the broader category of ‘Denotified Nomadic and Semi-Nomadic Tribes’ that, according to government estimates, number some 110 million across India. These communities have traditionally earned their livelihood moving from place to place, making weapons and iron implements, performing on the streets – as musicians, puppeteers, jugglers, snake charmers and similar – herding livestock, selling traditional medicines made with herbs or hunting wild animals. The story of their present-day exclusion begins in British colonial times when, with the enactment of the Criminal Tribes Act 1871, the colonial government characterized specific ethnic groups as ‘addicted to the systematic commission of non-bailable offences’ such as thefts. Describing Ghiyaras as ‘habitually criminal’, the law imposed restrictions on the movements of these communities, with adult male members forced to report weekly to the local police. In 1952, after independence, the Criminal Tribes Act was repealed and some 150 communities were denotified, hence the term ‘denotified tribes’.

But that did not prevent the continued stigmatization of Ghiyaras and similar groups. Various laws passed by state governments and central government since independence have adversely affected the livelihoods of denotified peoples. Soon after the repeal of the Criminal Tribes Act, many states passed a Habitual Offenders Act (between 1952 and 1959), bringing those communities within the scope of this law, yet again curtailing the freedom of the groups. Subsequent legislation adversely affected the livelihoods of the groups without providing any alternative sources of income. The Prevention of Begging Act (1950) particularly affected groups such as Ghiyaras, who traditionally survived by holding street shows but now found themselves harassed by the police and frequently charged under the act. Communities that depended on wild animals for performances were also deprived of their livelihood with the enactment of the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act (1960) and the Wildlife Protection Act (1972). Other pieces of legislation, the Medical Council Act (1956) and the Drugs and Magic Remedies Act (1954) rendered many traditional occupations ‘illegal’. More recently, legislation concerning cattle, such as the Rajasthan Bovine Animal (Prohibition of Slaughter and Regulation of Temporary Migration or Exports) Act 1995, banned the traditional occupation of cattle herding and trading groups in Rajasthan and Haryana.

In the context of the social prejudice the groups have suffered for centuries – mainstream society has yet to accept them as equals and they are still perceived as criminals, giving rise to frequent complaints of police harassment – the loss of traditional livelihoods and the absence of sustainable alternatives has driven such groups to migrate, in search of both new livelihoods and greater equality elsewhere. It was this search that drove Ghiyaras from Rajasthan to the outskirts of Delhi a quarter of a century ago, and which keeps them there, living in dire conditions in the hope of recognition and opportunities.

Today, most of the so-called denotified and nomadic communities have become settled, with some taking up newer professions, mostly low-skilled occupations such as construction work, domestic help, rag-picking, begging and so on, with little livelihood security and earning barely enough to survive. Evidently, there is little in the Indian growth story for Ghiyaras and other groups in similar circumstances, however close they might be to the engines of that growth. A recent survey on eight denotified and nomadic communities in Delhi found that, besides the lack of secure habitation, only a small proportion of households had access to adequate sanitation, while health care and education were also out of reach for most of them. A key element in this, the study found, besides state indifference and lack of documentation, was the constant threat of displacement that these communities faced from authorities – a situation of protracted uncertainty that meant many were not in a position to enrol their children in schools.

Pradhan is a cynical man. His scepticism is shared by his kinsfolk. But so is his stoicism. ‘We have tried our best to get what we deserve. We have the same rights as anyone else, so why are we neglected and denied those rights?’ he says. ‘We have knocked on every door. But nothing has worked. Like you, many people, including media persons, have come and spoken to us, interviewed us, written about us, shot films. And they have come again. But our life has not changed. But we will keep fighting for our rights, regardless.’

-

By Charlotte Graham

Across the Middle East, thousands of sub-Saharan migrants – including workers stranded by conflict, asylum seekers fleeing violence and others attempting the dangerous journey to Europe – have become some of the region’s most vulnerable people, targeted by traffickers and militias alike. But in Israel, where for years a community of Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers has resided, their hopes of sanctuary are giving way to apprehension as nationalists seek to deport the so-called ‘infiltrators’ from the country.

Amid ongoing crisis and insecurity in sub-Saharan Africa, increasing numbers of asylum seekers have migrated in recent years to Israel through Egypt. More than 90 per cent of them originate from Eritrea and Sudan, both countries with deplorable human rights records: while Eritreans flee the oppressive rule of unelected President Isaias Afwerki and all the human rights abuses that come with a dictatorship, Sudanese seek to escape the continued violence in Darfur and the country’s deteriorating economic situation. The road to Israel is long and hard, with those making the journey suffering abuse, kidnapping, torture and extortion on the way to what many hope will be asylum. Women and girls are especially vulnerable, and many refugees die en route to Israel or other countries.

However, their reception in Israel has been far from welcoming. While Eritreans in particular receive high rates of refugee recognition in European nations, African asylum seekers in Israel are not afforded the same acceptance. Despite being a signatory to the UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, Israel has granted official refugee status to just 11 of the approximately 35,000 Eritreans and Sudanese in the country. Until early 2018, when the Israeli Supreme Court suspended the detention of asylum seekers until a clear pathway for voluntary resettlement was in place, more than 1,200 asylum seekers were being held in detention facilities. By then, large numbers of Eritreans and Sudanese had already been ‘voluntarily’ deported by being threatened with indefinite detention if they did not leave.

These issues were brought to the fore by the Israeli government’s announcement in January 2018 that tens of thousands of sub-Saharan African refugees would be paid a sum of US$3,500 each in exchange for leaving the country, with a free air ticket to their country of nationality or ‘third countries’ (though officially unconfirmed at the time, these were identified as Rwanda and Uganda). This move was condemned as illegal by the UN, who subsequently brokered an arrangement in April in which Israel agreed that some 16,000 sub-Saharan Africans could be resettled in Western countries while granting temporary residency to an additional 16,000 sub-Saharan refugees in Israel. This deal, however, was cancelled shortly afterwards by the Israeli government. At the time of writing, it remains unclear what the fate of thousands of sub-Saharan Africans in Israel will be. As the deals with Rwanda and Uganda also fell through, authorities are currently unable to undertake any further forcible deportations. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has threatened to reopen recently closed detention facilities where hundreds of asylum seekers had been incarcerated for months at a time.

These recent developments cannot be separated from the reality of widespread racism in Israel towards sub-Saharan Africans – most of whom are classified as ‘infiltrators’ by Israeli authorities. Even for those not currently detained, life is difficult, with tens of thousands concentrated in inadequate housing in marginalized areas of south Tel Aviv where they have also faced rising levels of hostility, including property destruction, egg-throwing, racist demonstrations and other forms of harassment. While this prejudice has been challenged by a broad and vocal response from civil society groups within Israel, others have used their positions of power to vilify the country’s African population. In March 2018, Netanyahu suggested that African migrants posed a greater threat to Israel than terrorist attacks from Sinai and, in the same month, the Sephardic chief rabbi of Israel, Yitzhak Yose, notoriously described black people as ‘monkeys’ in a public sermon.

For the significant numbers of sub-Saharan Africans already deported from Israel, the situation is even harder. Research conducted by NGOs on those previously deported to Rwanda and Uganda found that none had been granted residency on arrival, leaving them with an irregular status and thus at constant risk of being returned to their countries of origin. As a result, many of those already deported from Israel have chosen instead to take the dangerous migrant route through Libya and attempt to cross the Mediterranean into Europe – a journey which claimed an estimated 3,139 lives in 2017. While the exact origin of the majority (2,215) of these deceased individuals is unknown, of the 924 whose region of origin was recorded 823 were from sub-Saharan Africa. Interviews by UNHCR with refugees in Rome – who, after being deported from Israel, chose to make the difficult journey to Europe – have highlighted the violence, exploitation and abuses they experienced along the way, travelling through multiple conflict zones before risking their lives to reach Italy.

While thousands of sub-Saharan Africans remain in limbo in Israel, there have been few signs that attitudes among the nationalist right wing have softened. The lack of a resolution, as well as the prospect of further detention, leaves many with few opportunities to build their lives meaningfully after the trauma of fleeing the insecurity and chaos in their home countries.

Header photo: African asylum seekers during a protest march in Tel Aviv, Israel, call on the government to recognize African migrants as refugees. Credit: Ahikam Seri / Panos.

-

By Catrinel Motoc

Roma, one of Europe’s most marginalized minorities, continue to be targeted in many countries with forced evictions – a situation that locks them into a cycle of displacement and human rights violations that affect every aspect of their lives. In Italy, this phenomenon has been especially pronounced, with an increasing number of informal settlements demolished by authorities across the country.

The destruction of Gianturco

On 7 April 2017, the Roma informal settlement of Gianturco, in the city of Naples, southern Italy, was demolished. All that was left of it after the bulldozers had finished were a few toys and pieces of furniture abandoned in the rubble.

For several years, around 1,300 Romanian Roma, including hundreds of children and elderly, sick and disabled people, had called this place ‘home’. Many had left Romania in search of a better future. ‘If there was work at home [in Romania], we would not have come here’, said one of the Gianturco inhabitants shortly before the April 2017 forced eviction. In fact, acute poverty, lack of access to health care, inadequate living conditions and forced evictions, coupled with deep-rooted discrimination grounded in centuries of persecution and discrimination, are among the many factors that push thousands of Romanian Roma to travel abroad to countries like Italy, France, Spain and elsewhere in search of a better life for themselves and their children.

But even once they made it to Italy, many Roma, like the Gianturco residents, faced a harsh reality. Most of them had already lived through countless forced evictions before settling there, in the hope of finding some stability in their lives.

Many of the houses had been built painstakingly by their inhabitants, using whatever materials were available, and slowly improved over time with the limited resources they had. It took local authorities just four hours to raze the entire settlement to the ground. By eleven o’clock that morning, Gianturco no longer existed.

The threat to the community first came in January 2016, when a court issued an order for the eviction, giving families just 30 days to leave the privately owned land where Gianturco was located. But these families had nowhere else to go. While the municipality managed to negotiate some extensions of the deadline to delay the eviction by a year or so, they failed during those months to carry out a genuine consultation to explore possible alternatives to the eviction and rehousing options for all of the affected inhabitants.

As a result, on the morning when the demolitions began, there were still around 200 people still living in the settlement: while many had already left, driven out by ongoing harassment by police in the run-up to the eviction and the fear of what would happen to them if they stayed, some simply had nowhere else to go. Cristina was among those who stayed. ‘I came here to build a life. I have had two operations. Where do I go? What do I do?’ she said, in tears. ‘We go on the streets,’ answered her husband, while packing up their few treasured belongings.

One girl at Gianturco on the day of the eviction stood with her brother and watched the bulldozers approaching their homes. ‘Here we were fine,’ she said. ‘We liked it. We had three rooms, one for me, one for my brother, and one for my parents. The house was big. Where they will take us, we don’t know how it will be.’

Following the forced eviction and the sealing of the area, around 130 of Gianturco’s residents were relocated to a new segregated camp on Via del Riposo. Segregated by a fence from the surrounding area, it comprised a small concrete area on which dozens of containers sat. Years ago, there was apparently another camp which was set on fire by unknown assailants. When the families were relocated there on 7 April, graffiti on the wall opposite the camp read ‘No to Roma’ – a stark testament to the hatred and discrimination Roma still face in Italy and elsewhere in Europe.

These containers were the only housing offered to around 20 of the Gianturco families, based on criteria that were never clearly and transparently explained by local authorities, while a few others were accommodated in a reception centre in town. They were, however, the ‘lucky’ ones: for hundreds of other families that once lived in Gianturco, there was nothing. Some moved in with friends temporarily, while many others spent weeks sleeping rough in parks, abandoned buildings and cars. A large number of those uprooted were left with no other choice but to move to other informal settlements elsewhere in and around Naples, placing them at risk of threat of forced evictions in the near future.

The situation of Italy’s Roma

The eviction of the Gianturco settlement is not an isolated incident: indeed, it represents a sad but by no means untypical example of the widespread and entrenched discrimination Roma face in Italy. International and national human rights organizations have for years documented a pattern of human rights abuses perpetrated against the country’s Roma: segregated camps, lack of access to social housing and a repeated cycle of forced evictions remain a daily reality for many of the 120,000 to 180,000 Roma estimated to be living across Italy.

In February 2012, the Italian government adopted its National Strategy for Roma Inclusion, aiming to define the roadmap for public policies until 2020. Among other actions, it proposed the gradual elimination of poverty and social exclusion among marginalized Roma communities in the areas of education, health care, employment and housing. The strategy promised to ‘overcome’ informal settlements and recognized that forced evictions had disproportionately targeted Roma in Italy. But, while farsighted on paper, more than six years on, the grand ambitions of the National Strategy ring hollow: no concrete progress has been achieved in implementing sustainable integration and housing policies. Successive Italian governments have failed, or not even seriously tried, to address the community’s exclusion.

The list of forced evictions carried out in recent years in cities across the country bears this out. According to the Rome-based Associazione 21 Luglio, an organization working for many years to document the human rights abuses suffered by Roma, in 2017 alone at least 230 forced evictions of Roma were registered across Italy, with hundreds if not thousands of people displaced. Those affected are frequently not provided with adequate information about the eviction, let alone genuinely consulted about feasible alternatives, and often families may find out about an eviction just a few days before it takes place. In many cases they are not given any legal documentation such as court orders or individual notices, nor the chance to challenge the eviction and seek an effective remedy. Alternative accommodation is often unavailable or only consists of temporary accommodation for women and children in public dormitories and emergency shelters.

These forced evictions have devastating consequences that extend well beyond the immediate trauma of displacement. Having been rendered homeless, families usually have no alternative but to rebuild improvised dwellings elsewhere, often in even more precarious living conditions than before. This traps them in a vicious circle of continuous forced evictions that, with each new wave of damage and disruption, places education and employment further out of reach.

The chilling pattern of forced evictions of Roma in Italy needs to be read in conjunction with the long-standing and systematic policy of authorities to build and maintain formal camps for Roma. Thousands of families are currently living in segregated, mono-ethnic camps set up by authorities across the country specifically for Roma. Associazione 21 Luglio’s most recent data shows that 148 formal camps have been built in 87 cities and towns across the country, housing some 16,400 inhabitants, while the number of people living in informal settlements is almost 10,000. This trend is only likely to continue, with the promise of the recently formed national government in May 2018 to forcibly close all informal Roma settlements, potentially affecting thousands of people.

Regional and municipal regulations enable Italian authorities to construct and administer Roma-only camps, often located far away from basic services in areas unsuitable for human habitation, such as near waste damps and airport runways. Living conditions in these camps are frequently inadequate, failing to meet international human rights standards and even national regulations on housing. Tellingly, in many cases, the option of being rehoused in camps is only offered to Roma by the authorities following forced evictions from informal settlements. One example is the relocation in 2013 of a group of Roma men, women and children in La Barbuta, a Roma-only camp next to the Ciampino airport runway in Rome: despite the Rome Civil Court ruling in 2015 that the relocation was discriminatory, they remain there to this day. Municipal authorities, while recently announcing their intention to close down the camp, have yet to offer clear details of what this would involve.

The responsibility for these human rights violations lies not only with the Italian government, but also with the European Union, which to date has failed to take any effective action against these abuses beyond a preliminary investigation in 2012 that has yet to develop into concrete proceedings for violation of EU law. Nor is Italy alone in the widespread discrimination perpetrated against its Roma population, which numbers around 10 to 12 million in Europe as a whole. Across the region, hundreds of thousands of Roma live in informal settlements as a result of policies that deny them adequate housing options. This is often part of a wider backdrop of discrimination and exclusion, from substandard Roma-only schools and classes to violent attacks and hate crimes that overshadow their lives. Until substantive, politically meaningful policies are put in place, there is no end in sight to the segregation of Roma and the discrimination against them.

Header photo: Cristina, a Roma woman who stayed in the Gianturco settlement, Italy, as her community was evicted. Credit: Amnesty International / Claudio Menna.

-

By Elisa Oddone

With more than 5.6 million Syrians now living outside the country, predominantly in neighbouring Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, the conflict has created a vast refugee population facing poverty, discrimination and insecurity. But for certain communities, such as the long-stigmatized Bani Murra, the present crisis has only reinforced a long history of prejudice and exclusion – placing them in an especially vulnerable situation as both foreigners and a minority.

Winds spread dust over dozens of makeshift tents on a desolate patch of desert highway in Irbid in northern Jordan, just a few metres from the constant traffic on the road. Clothing dries on makeshift washing lines, surrounded by filthy ponds and piles of rubbish, while stray dogs hunt for leftovers in the remains of campfires where meals have been prepared.

Around 60 members of Syria’s Dom community, an Indo-Aryan people also known as Bani Murra, live here. Frequently referred to as ‘gypsies’ due to their formerly nomadic lifestyle, they fled their country at the beginning of the Syrian conflict in 2011. They share this plot with dozens of Turkmen, a close-knit Turkic-speaking community which has been in the kingdom for decades. Researchers believe Dom migrated from South Asia in the sixth century and gradually made their way through the Middle East, with settlements already in place at the time of the Crusades.

A Bani Murra child pauses behind a pond filled with rain water and trash. The makesift camp sits just off the highway in northern Jordan and offers little sanitation or water safeguards. April 2018.

Turkmen children approach a Bani Murra portion of the camp both groups share in northern Jordan. Though they live as neighbors, the groups differ in customs, language and culture. April 2018. ‘We come from the southern city of Dara’a,’ says resident Alaa Mursalli, playing with the eldest of his five children in their two-room tent. ‘We moved after the first week of fighting. Electricity and water were cut off. Shootings were constant, we couldn’t stay. So, we crossed with 80 other people from our tribe into Jordan and eventually relocated here.’

The gaunt 35-year-old says that before the war started, his family and relatives lived in neighbouring flats in the city’s outskirts and often entered Jordan for seasonal work or to visit other members of his tribe. Since then, along with more than 600,000 other Syrians now residing in the country, Jordan has become his home. However, official figures about the Bani Murra community, both among Jordan’s refugee population and back in Syria, are not available: unverified data show that there were approximately 300,000 Dom in Syria before the conflict, with unofficial figures suggesting they could have been as many as 1 million. A few hundred of them are now scattered between areas of northern Jordan and the Azraq refugee camp, home to over 36,000 refugees. Like Europe’s Roma, Dom are a persecuted minority who face widespread prejudice and hostility across the region. Due to popular stereotypes associating them with witchcraft, fortune-telling and criminality, they are often referred to as ‘nawar’ or ‘tramps’ – a slur that Bani Murra have also adopted themselves.

Thirty-five-year-old Bani Murra Alaa Mursalli fled Syria’s southern city of Dara’a with his family at the inception of the civil war in 2011. April 2018. The 70-year-old Bani Murra leader in the camp, Ghurdru Marsalli, explains that his tribe is made up of several members related to each other. ‘Some of us have Jordanian nationality as a result of marriages that happened 40 years ago with local Bani Murra. Others are just Syrian nationals. But we all used to live in Syria,’ he says, gesturing with hands adorned with simple traditional tattoos. ‘We were poor back home. Still, we lived in houses and had jobs, and our children went to school. Bani Murra who moved here have become 100 per cent poor.’

Historically, Dom communities have always been marginalized from wider society, with limited access to education and higher levels of unemployment. But Jordan’s soaring living costs have now condemned them to a life of misery. Jobs that Bani Murra migrant workers used to take before the war and that guaranteed a decent living back in Syria, like picking vegetables and fruit in the Jordan Valley, are now of little help.

Kasi al Mursalli, 39, a palm reader, helps her brother Alaa and his wife raise their children while occasionally working in the fields. She just returned from the Jordan Valley, but explains that the money she made this year will not be enough to cover their expenses in the kingdom. ‘Back in Syria, I picked tomatoes, olives, beans and apples. A truck collected women, men and children in the morning. We earned very little. Still, it was more than enough because life was extremely cheap and we were allowed to take some vegetables and fruits from the harvest. This is not the same here.’

Widespread suspicion towards Dom is a further barrier to employment, with many applicants being rejected due to their background. The tribe recounts the case of a member who approached the factory across the street for a position a year earlier. An answer is yet to come. Meanwhile, they say, other men from the area have been hired on the spot.

Syrian Bani Murra men pose for a portrait outside a shanty camp they share with ethnic Turkmen. The group says discrimination and social exclusion in Jordan makes finding a job difficult. April 2018. ‘Across the region, people have a negative image of us. They think we are up to no good,’ Alaa says. ‘Sometimes, the truck selling water doesn’t stop, or when we ask our neighbours for a glass of water, they tell us to go away because we are gypsies.’

Ghurdru, the head of the family, says the government has failed to provide them with any help to date. Nor has the local Bani Murra community in Jordan shown much support so far. Besides a few cross-national marriages between Dom living on the border, Jordan’s 70,000-strong community distances itself from the Syrian one.

Despite themselves being socially stigmatized and lacking any form of representation in the country, Jordanian Bani Murra are reluctant to mix with their Syrian counterparts. ‘Our relation is very weak,’ Fatih Moussa, one of the leaders of the Jordanian minority, says in his home in Amman. ‘They entered Jordan as a result of the war. Even their habits are different from ours, just as the habits of Jordanians differ from those of the Syrians. We are closer to the Bedouins than to them, in terms of habits and traditions.’

A mountain of trash overlooks a shanty camp in northern Jordan split by Bani Murra and Turkmen minority groups. April 2018. Around 30 km from the shanty camp, a desert village near the Jaber border crossing point is home to around 300 Syrian Bani Murra residing in some 30 houses and a few tents. Alaa’s brother Hazem Mursalli lives here. Two goat carcasses hang outside, dripping blood into the dust: Hazem explains the goats will be cooked on Friday for the whole community. Relatives from the camp will also join the feast. Talks about the quality of the meat among men are carried out in the Domari dialect, the Romani language in the region. Hazem says everyone in his community uses it and that it is preserved and transmitted orally from one generation to the next. When their dialect lacks a word, he explains, they borrow it from the local Arabic.

‘In Syria, we were over a million. The majority lived in Aleppo, an historical hub for gypsies in the Middle East,’ says the 37-year-old man. ‘Because of our large numbers, racism back home was stronger than in Jordan. But we are good people, trust me, we don’t look for problems.’