Azref i Tamezla – “The right to diversity”

A trip to Southern Tunisia

By Silvia Quattrini (Middle East and North Africa Programmes Coordinator)

Tamazret is a village in Southern Tunisia (in the governorate of Gabes), almost a six-hour drive from the capital Tunis. Tamazret’s name comes from the Tamazight expression ‘Tamazra’ (I see you). Indeed, Amazigh people used to build their villages in the mountains by digging houses in the rocks to have visibility from above and protect themselves from attacks. Today there is only an estimated few hundred inhabitants left.

Mongi Bouras’ family originally came from this village, but he was born and raised in Tunis. When he turned 35, he decided to move to Tamazret, bought a nearly collapsed house and created a Berber museum out of it. ‘People thought I was crazy,’ Mongi says. It is the second time we visit his museum in two years, and it keeps improving thanks to his efforts. It is where our first meeting with some Amazigh representatives and activists takes place. But first Mongi gives us a tour and explains proudly about ancient traditions concerning marriage and society, some of which are still in place.

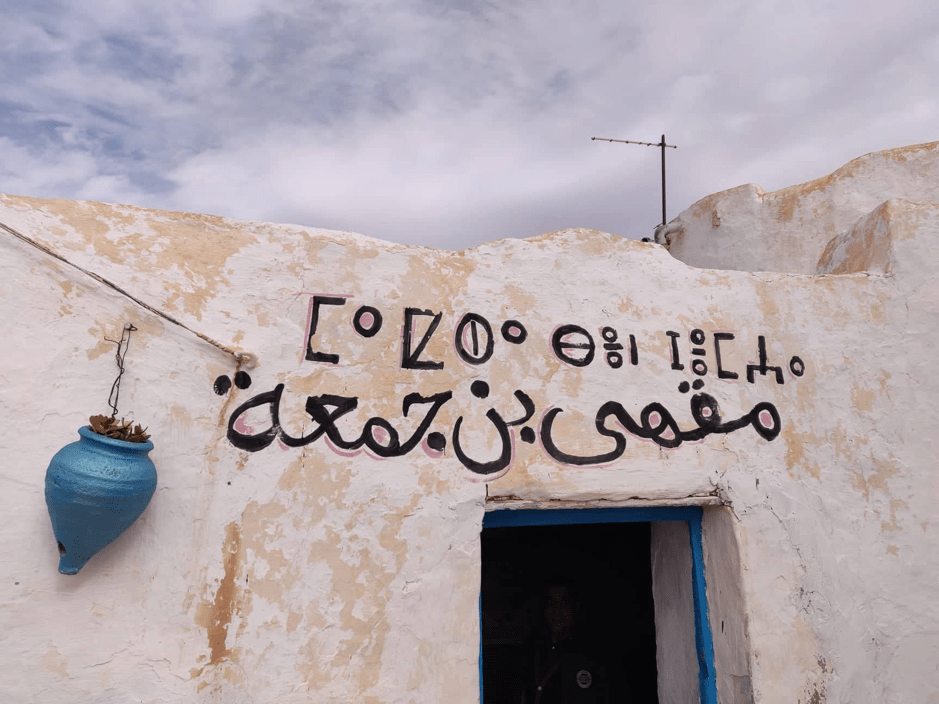

The meeting we attended was a two-day meeting about Amazigh language and culture, organised by the Tunisian Association for Amazigh Culture (Association Tunisienne pour la Culture Amazigh). Its former president and now member, Jalloul Ghaki, welcomes us warmly and introduces the participants. Most of them are men, but there are also some female participants. Kawther Ben Jemaa is a young woman who recently re-opened the oldest café in Tamazret. It was not easy for her at the beginning because not everyone accepted the fact that a woman is running a coffee house, but her smile is contagious and everyone in the room seems really proud of her. She has also recently started running Tamazight language and theatre courses for children in her café in partnership with a school teacher.

The meeting room, the museum, the walls of the village, the coffee house, everything presents writings in Tifinagh (the Tamazight alphabet) and Arabic. I want to know who and to what extent still speaks the language. A man tells us he was a teacher in Tamazret and used to speak Arabic to the pupils, because it is the compulsory language of education, but the children would answer in Tamazight. Another man tells us that he and his wife speak Tamazight at home. Their children understand, but they answer back in Arabic. I try to have them explain why, but another man proudly interrupts us, ‘In my house, we only speak Tamazight, no Arabic. I speak Tamazight even to my goats and my chicken.’

Jalloul hands me a copy of the recommendations that the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights addressed to the Tunisian state in 2016, during their last review, which can be summarised as follows:

- Recognising the language and culture of indigenous people,

- Taking administrative and legal steps to ensure the teaching of the Amazigh language and promoting knowledge of the history and culture,

- Lifting decree no.85 of 12 December 1962 which prevents registering Amazigh names at birth, and

- Facilitating the activities of the Amazigh cultural associations.

This was a great achievement, as for the first time a UN body addressed such recommendations to Tunisia. But participants insist that none of this was implemented yet in the last three years.

Just a couple of weeks ago, Lamia Haouet, a member of the association, participated with MRG to the UN Forum on Minority Issues and raised some of the above points before the Forum. ‘Why in Tunisia, in addition to Arabic, we have the option to study French, Italian, Spanish, German, Chinese, Russian… but we don’t have the option to study Tamazight?’ she asked in Geneva on 29 November.

Before closing the first meeting, Habiba, another woman, reads a poem by Jalloul in Standard Arabic, it’s called ‘the right to difference’ (haqq lil ikhtilaf).

‘We have to respect others so that others also respect us. Without respect for diversity there’s no common living. Although we are not respected and our language is not recognised, we continue in a peaceful way because we are in our country,’ adds Jalloul when commenting the poetry.

Just a few months ago, a judge in Sfax issued a favourable judgment and allowed for the registration of a Tamazight name in the civil registry, but he was allegedly moved to a smaller town the following week.

Kahina stresses that they always have very friendly conversations with government representatives, but then no steps are taken. ‘Also, when you start speaking with people about the Amazigh issue, they ask you immediately whether you are Muslim. There’s always a lack of distinction between religion and identity.’

Tamazight of Tunisia is recognised as a severely endangered language by UNESCO with approximately 10,000 speakers left. Lamia, a linguist who has worked on Tunisian Tamazight since 2015, explains that there are currently 6 varieties of the language spoken in 6 areas of Southern Tunisia: Sened (disappeared), Tamazret, Taoujout, Djerba, Zraoua, Douiret and Chenini/Tataouine.

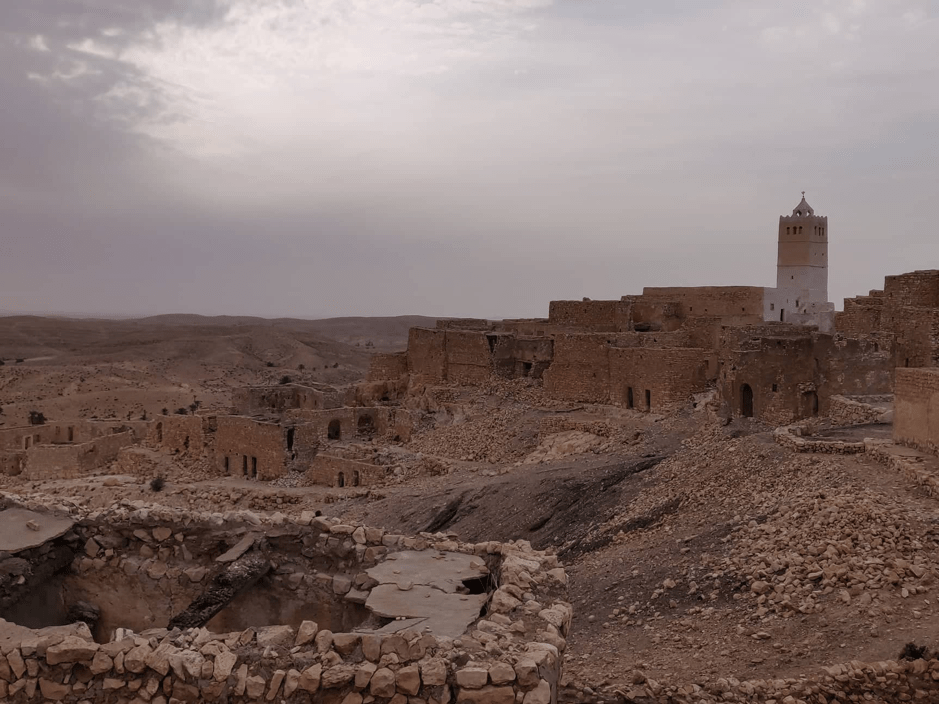

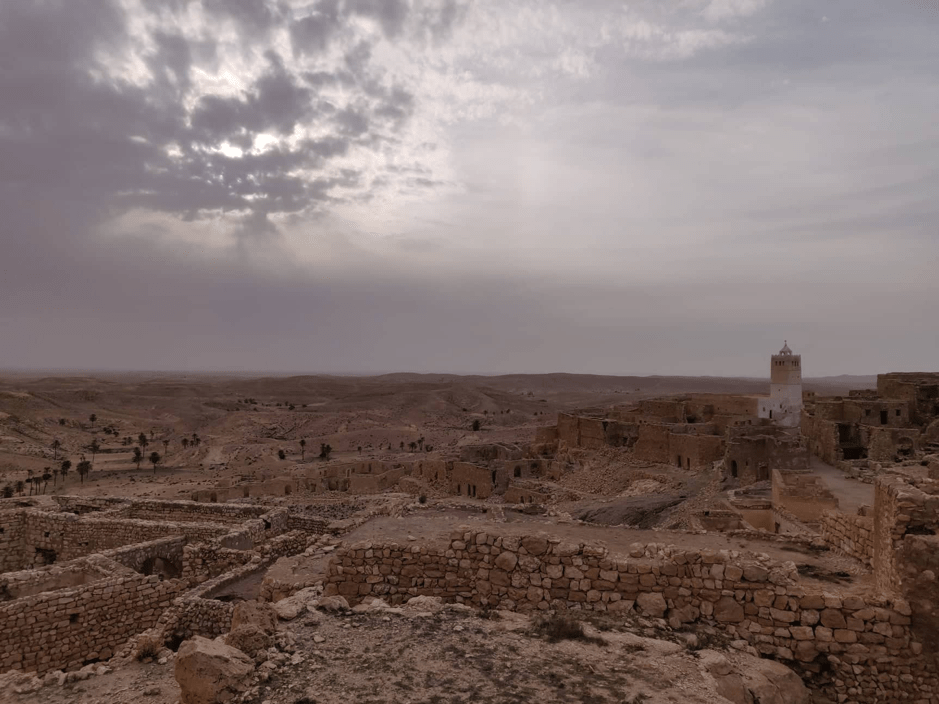

In the afternoon, we visit old Zraoua (Azrou in Tamazight, meaning ‘the great stone’). It is almost like a ghost village today, with only one family living there. People started leaving in 1965, Ali Zraoui’s family left in 1985. Many villages in this area have an old village and a new village. All the old villages are up on the mountain and the new ones are down in the valley. In the 1960s the state started building those new villages as a strategy to make people come down from the mountain and many did, because they had no access to water, electricity and other services in their traditional villages.

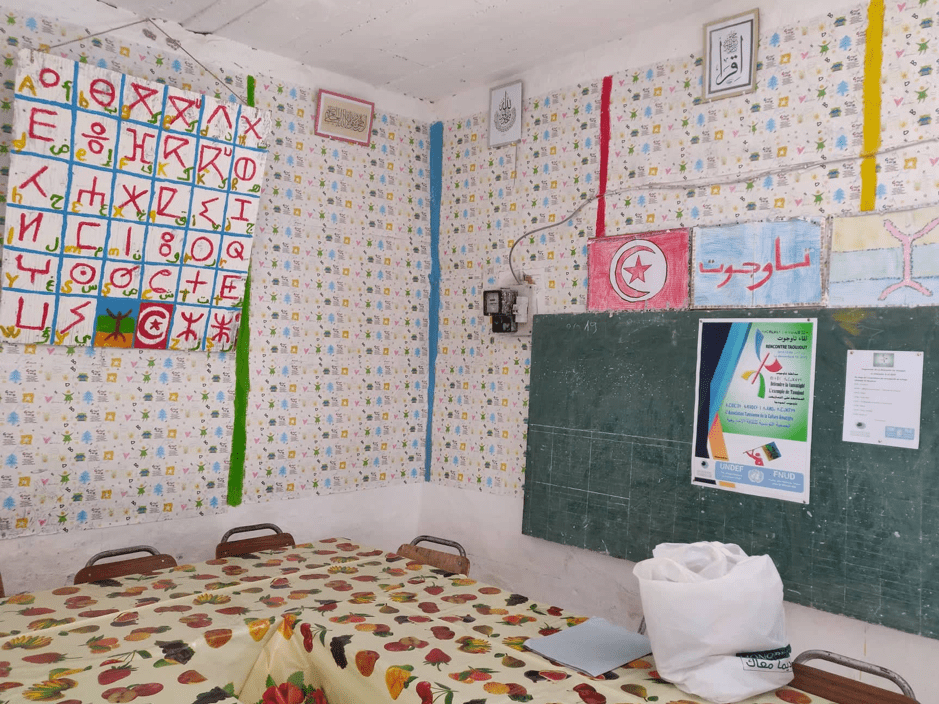

On the second day, we go to Taoujout, which is the only village still currently 100 per cent Amazigh-speaking. Also, here there are only a few hundred inhabitants left. Some people created an association starting with no budget (the association for the preservation of Taoujout’s heritage) and in whose small premises we are meeting. Boukha, a young lady from the village, explains that here they provide afternoon courses for pupils, especially those who have difficulty at school. The elementary school is just on the other side of the road. I ask whether the teachers in the school are from the village and whether they speak Tamazight. Some of them do, but most of them don’t because they are sent from other places. The children in Taoujout only speak Tamazight until they arrive in school, where Arabic is used, and on the first day they are faced with a language they don’t understand.

Jalloul stresses that in order to be part of this movement, it is important to be engaged in learning the language. ‘It is not a person’s fault not to be a speaker, but it becomes an obligation if we want to safeguard it, otherwise it will die.’ He explains that here they teach children how to write in Tifinagh. ‘It is easy to organise at the local level, but it is a limited action because the funding is very limited.’ He also stresses the importance of learning other languages, such as French and English, as it is an important tool towards accepting others, “but then our language is always considered not important, marginalised or associated with separatism”. We close the meeting with a poem written by Jalloul in Tamazight followed by a translation in Tunisian Arabic. People living in a multilingual reality often do not even realise how frequently they switch from one language to the other but during these two days, conversations were a beautiful mix of Tunisian Arabic, French, Tamazight and Standard Arabic.

There are currently 13 Amazigh associations in Tunisia, all registered after the revolution. They interact with each other, but their capacity is limited to small-scale action and coordination, and the government does not provide funding or support.

Minority and indigenous languages are a source of knowledge and constitute a fundamental part of communities’ identities. Their protection can ensure preventing societal tensions as well as the respect of fundamental human rights that are language-related, such as the right to education and to culture.

Find out more about the situation of minorities in Tunisia: https://minorityrights.org/publications/identity-and-citizenship-in-tunisia-the-situation-of-minorities-after-the-2011-revolution/

Read MRG’s latest report about the endangered languages in Africa and proposed solutions for their revitalisation: https://minorityrights.org/publications/language-rights-africa/